|

Free Online Illustrated Books for Kids |

Popular Andersen Fairy Tales Animal Stories Poetry for Kids Short Stories Categories list

P.Bazhov

The Malachite Casket

Translated by Eve Manning

freebooksforkids.net

Illustrated by V.Nazaruk

With springtime, the Young Master arrived. Came driving into Polevaya one fine day. The people were all called together, there were prayers in the church, and then all kinds of dancing and prancing in the Big House. A couple of barrels of wine were rolled out for the common folk too, so they could drink to the memory of the Old Master and the health of the new one. It was like priming a pump—the Turchaninovs were good at that. Add ten bottles of your own to the Master's goblet and then it would look like something, but at the end of it all you'd find your last kopek gone and naught to show for it.

The next day the people were back at work again, but there was still feasting and drinking in the Big House. And so it went on. They'd sleep a mite and then back to their carousing again. They'd go rowing about in boats, or riding horses in the woods, and then the music would start—there was everything you could think of. And all this time Flogger was drunk. The Master gave the wink to his hardest drinkers—fill him up and keep him that way. Well, of course, they were glad enough to curry favour with the new Master.

Flogger was drunk, but he'd a good idea what was coming, all the same. He felt awkward, ashamed like, in front of the guests. So when they were all at table, he burst out: "What do I care if Master Turchaninov takes my wife! He can have her for all of me! I don't want her. Take a look at the maid I've got!" And what does he do but pull that portrait from his pocket. They all gasped, and Flogger's dame, her mouth dropped open and she couldn't seem to get it shut again. As for the Master, he just stared and stared. And he wanted to know more.

"Who is she?" he asked.

Flogger just laughed. "If you heap the whole table wi' gold I shan't tell ye!"

But what was the good of that, when everyone knew Tanyushka! They all fought to be the first to tell him. But Flogger's dame, she kept arguing and trying to stop them.

"Stuff and nonsense! You don't know what you're talking of! Where'd a village maid get a dress like that, and gems, too? That portrait, my husband brought it from abroad. He showed it me before we were married. He's drunk, he doesn't know what he's saying. When he's sober he won't remember a word of it."

Flogger could see his wife was all in a taking and started snarling at her.

"You're a shameless hussy, that's what ye are! Trumping up a cock-and-bull tale to fool the Master! When did I ever show ye that portrait? I got it here. From that maid they're talking of. About the dress, I won't tell a lie, I don't know anything about it. You can put any dress on her. But the gems, she did have those. And now they're here, locked in your cupboard. You bought them yourself for two thousand, but you couldn't wear them. A Circassian saddle won't go on a cow. The whole village knows how ye bought them!"

The Master no sooner heard of the gems than he said: "Get them out, show me them."

Now that Young Master, hark 'ee, was a spendthrift, played ducks and drakes with his money. Like heirs often are. And he was real mad about gems. He couldn't boast much of looks, so at least he'd boast of jewels. As soon as he heard of fine gems, he'd be itching to buy them. And he understood about them right enough, though in general he hadn't much wits.

Flogger's dame saw there was no way out, so she brought the casket. And the moment the Master saw the gems he asked: "How much?"

She named a figure beyond all sight or reason. The Master started bargaining. They came to terms on the half, and the Master signed a paper for the money—he hadn't that much with him, you see. Then he put the casket on the table in front of him and said: "Send for that maid ye've been telling of."

Some of them went off running to fetch Tanyushka. She came at once, thinking naught of it—she expected some big order for work. She came into the room, and there it was full of people, and in the middle a man with a face like a hare, the same one she'd seen that time. And in front of the hare stood the casket, her father's gift. Tanyushka guessed at once it was the Young Master.

"What d'ye want of me?" she asked.

But it seemed like he couldn't speak. He just stared and stared at her. Then at last he found his tongue again.

"Are those your gems?" he asked.

"They used to be, but now they're hers," and she pointed to Flogger's dame.

"No, they're mine," said Turchaninov.

"That's your affair."

"Would you like me to give them back to ye?"

"I've naught to give for them."

"Well, you won't refuse to try them on—I want to see how they look when they're worn."

"I don't mind doing that," said Tanyushka.

She took the casket, sorted out the trinkets the way she was used to doing, and quickly put them on. The Master looked and he just gasped. Gasped and gasped and naught else. And Tanyushka, she stood there in the ornaments and said: "There they are. Have ye looked your fill? I've no time to be standing here. I've work waiting."

But right there, in front of them all, the Master said: "Marry me. Will ye?"

Tanyushka only laughed.

"It's not fitting to talk that way, Master, to one as isn't your equal." Then she took off the trinkets and went.

But the Young Master couldn't let her alone. The next day he came to her cottage to make his proposal in all form. He begged and urged Nastasya—give me your daughter.

"I won't force her one way or the other," said Nastasya. "Let it be as she says. But to my mind it's not suitable."

Tanyushka listened and listened, and then she said: "Here's my word. I've heard tell there's a chamber in the Tsar's palace decorated with the malachite my father got. If you show me the Tsarina in that chamber, then I'll be your wife."

The Master was ready to agree to anything, of course. He started off at once getting ready to go to St. Petersburg, and wanted to take Tanyushka with him—I'll get you horses, he said. But Tanyushka told him: "It's not our custom for a maid to use a man's horses before she's wed, and we're still naught to one another. We'll talk of that later on, when ye've kept your word."

"When will you come to St. Petersburg, then?" he said.

"I'll be there by Intercession Day," she said. "Ye can rest easy about that. And now go."

The Master left; of course he didn't take Flogger's dame with him, didn't even give her a look. As soon as he got back to St. Petersburg he told the whole town about the gems and the maid. He showed the casket to many. And of course folks were real curious to see the maid. By the autumn he'd got a house for her, and bought all kinds of robes and shoes and put them ready. And then she sent word she had come, and was living with some widow right on the edge of the town.

Of course Turchaninov went straight off there.

"Why are you here? How can you live in a place like this? I've got a house all ready, you couldn't want a better."

But all Tanyushka said was: "I'm quite comfortable where I am."

The talk about the gems and Turchaninov's maid got to the Tsarina too. "Let Turchaninov show me that bride of his," she said, "for what's told of her is beyond belief."

Off he went to Tanyushka—she must get herself ready; she must have a robe to wear at court, and put on the gems from the malachite casket.

"About my dress ye needn't concern yourself," she said, "but the gems I'll take as a loan. Only mind ye don't think of sending horses for me. I'll come my own way. Wait for me by the entrance to the palace."

Turchaninov wondered a good bit—where would she get horses? And a court robe? But he didn't dare ask.

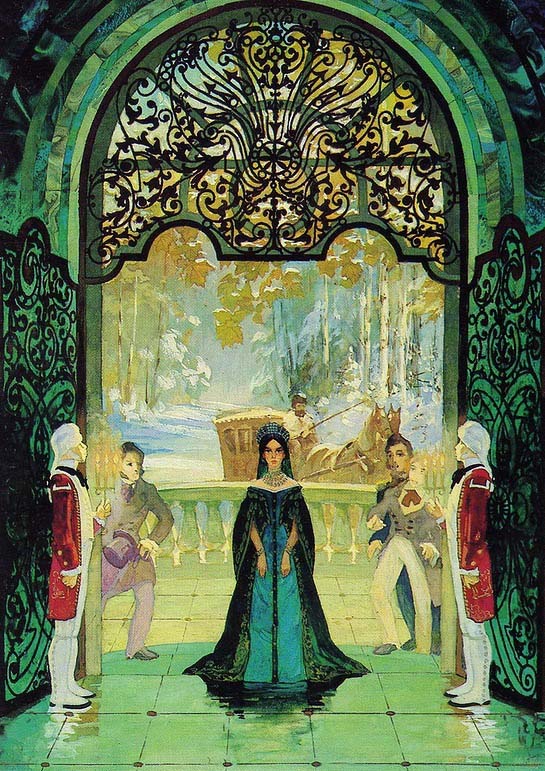

All the grand folks gathered at the court, they came rolling up in carriages, in their silks and velvets. Turchaninov was early by the door, fidgeting about, waiting for Tanyushka. And there were others curious to see her, they stood about waiting too. But Tanyushka, she put on the gems, fastened a kerchief round her head the village way, put on her sheepskin and came along quietly on foot. And the folks who saw her, they wondered where she'd come from and followed her in a crowd. She came to the palace but the lackeys wouldn't let her in. "Villagers can't come in here," they said. Turchaninov saw her when she was a good way off, but he was ashamed to have his bride come on foot and in a country sheepskin, so he went and hid himself. Tanyushka opened her sheepskin and the lackeys stared. That robe—why, the Tsarina herself hadn't one like it! They let her in at once. And as soon as Tanyushka took off her kerchief and sheepskin all the people gasped in wonder and started asking: "Who is she? What land's this Tsarina come from?"

Turchaninov was there in a moment.

"This is my bride," he said.

But Tanyushka looked at him very sternly.

"That's still to be seen," she said. "Why didn't ye keep your word, why weren't ye at the entrance?"

Turchaninov mumbled and stumbled, there'd been a mistake, please forgive him, and so on.

They went into a chamber of the palace, the one where they were told to go. Tanyushka looked round and saw it wasn't the right one.

"What's this, are ye trying to deceive me?" she asked, more sternly still. "I told ye it must be the chamber that's decorated with the malachite my father got." And she started walking through the palace just as if she were at home there. And all the senators and generals and the rest followed after her. "What's this?" they said. "That must be where we're all to go."

The people crowded in till it was as full as could be, and all of them staring at Tanyushka. And as for her, she stood close up to the malachite wall and waited. Of course Turchaninov was there right by her. He kept babbling that it wasn't fitting, the Tsarina had said they were to wait for her in another chamber. But Tanyushka stood there quietly, didn't even move an eyebrow, just as though he wasn't there at all.

The Tsarina went into the chamber she'd said and found it empty. But her informers quickly told her that Turchaninov's maid had led them all away to the Malachite Hall. The Tsarina scolded, of course—such high-handed goings-on!—and she stamped her foot, too. She was a bit angry, you see. Then she went to the Malachite Hall. Everybody bowed low, but Tanyushka stood there and never moved.

"Now then," said the Tsarina, "show me this high-handed maid, this bride of Turchaninov's!"

When Tanyushka heard that she frowned and said to Turchaninov: "What does this mean? I told ye to show me the Tsarina, and you've done it so as to show me to her. You've lied again! I don't want to see any more of ye. Take your gems!"

With those words she leaned against the malachite wall—and melted away. All that was left was the gems sparkling on the wall, stuck there in the places where her head, neck and arms had been.

Of course all the courtiers were real scared and the Tsarina swooned right away. There was a great to-do till they'd raised her. Then when everything had quietened down a bit, Turchaninov's friends said to him: "Take your gems, at least, before they're stolen. It's the palace you're in! Folks here know their value."

So Turchaninov started trying to pick them off the wall, but each one he touched turned into a drop—some clear like tears, others yellow, and others thick and red like blood. So he got none of them. He looked down and there on the floor was a button. Just a glass button, bottle glass, it looked like. A worthless bit of a thing. But in his trouble he even picked that up. And as soon as he had it in his hand, it was like a mirror and the green-eyed maid looking out of it, wearing the precious gems, and laughing and laughing.

"Eh, ye stupid cross-eyed hare!" she said. "For you to think of getting me! What match for me are you?"

After that Turchaninov lost the last of his wits, but he didn't throw away the button. He'd keep looking in it, and it was always the same thing he saw—there stood the green-eyed maid and laughed and laughed and mocked him. He was so cast down he started drinking, and got into debt right and left, our village and mines almost went under the hammer in his time.

As for Flogger, after he was put out of his job he spent his time in the tavern. He drank all he had, but he still kept that portrait in silk. What happened to it after, nobody knows.

Flogger's dame was left empty-handed too. Try to get your money on a note of hand when all the iron and copper's mortgaged!

About Tanyushka nobody ever heard a word more from that day on. It was just as though she'd never been.

Nastasya grieved, of course, but not over much. Tanyushka, you see, had always been like a changeling, not like a daughter to her at all. And then, the lads had both grown up. They got married. There were grandchildren. Plenty of folks in the cottage. Plenty to do and think of—watch one, give a slap to another—no time to brood!

But the young fellows didn't forget Tanyushka for a long time. They still came round Nastasya's window. Maybe some day she'd be there. But she never was. Then in the end they got married one by one, but time and again they'd remember: "Eh, that was a rare maid used to live in our village! Ye'll never see another like her."

But there was one other thing; talk started going round that the Mistress of the Copper Mountain had a double: folks would see two maids in malachite robes, two of them together.

Please support us

PayPal: anfiskinamama@gmail.com

Contact us if you have any questions or see any mistakes

© 2019-2025 Freebooksforkids.net