|

Free Online Illustrated Books for Kids |

Popular Andersen Fairy Tales Animal Stories Poetry for Kids Short Stories Categories list

P.Bazhov

The Malachite Casket

Translated by Eve Manning

freebooksforkids.net

Illustrated by V.Nazaruk

Nastasya, Stepan's widow, was left the malachite casket with every kind of women's ornaments in it. There were rings and earrings and all sorts. The Mistress of the Copper Mountain herself had given it to Stepan before he married.

Nastasya had grown up an orphan, she wasn't used to such rich things, and she didn't like making a lot of show either. At first, when Stepan was alive, she used sometimes to put on this or that. But she never felt easy in them. She'd put on a ring, you'd say it fitted just right, neither too tight nor too loose, but when she'd go to church in it or to visit friends, her finger would start aching as if it was pinched and the end would even turn quite blue. If she put on the earrings it was worse still. They'd pull and pull on her ears till the lobes were all swollen. Yet if you picked them up they didn't seem any heavier than the ones she always wore. The necklace, six or seven strands of it, she only tried on. It felt like ice round her neck and never got any warmer. And anyway, she was ashamed to let folks see her in a thing like that. "Look at her, all decked out like a tsarina," they'd say.

Stepan didn't try to make her wear them, either. He even said once: "Better put them away, lest misfortune befall."

So Nastasya put the casket in her bottom chest, underneath the others—the one where she kept her store of homespun and things of that sort.

When Stepan died and they saw the stones in his hand, it happened that Nastasya showed the casket to some folks. But that man who knew about all those things, the one who told them what Stepan's stones were, they say he warned Nastasya: "Mind out, see ye don't sell that casket for naught. It's worth many a thousand."

He'd got learning, that man, and he was free, too. Once he'd been foreman at the mine, but they took him off it. He was too easy on the men. Well, and he liked his glass too. Always in the tavern, he was, though I should speak no ill of the dead. But in all else—a real good man. He could write a petition or mark off sections, and he made a proper job of it, not like some. Our folks would always treat him to a glass on holidays, whoever else might be left out. He lived like that in our village till he died. The people kept him going.

Nastasya had heard from her husband that the foreman was an honest man with a good head on him, the only trouble was the drink. And she heeded what he said.

"So be it," she said, "I'll keep it for a rainy day." And she put the casket back in its old place.

They buried Stepan and mourned forty days, all right and proper. Nastasya was a fine, comely woman, and well off, so suitors soon started sending matchmakers. But she'd got plenty of sense.

"A second, though he's good as gold, still he's but a stepfather to the children."

So after a time they let her alone.

Stepan had left his family well off, as I say. They had a good solid house, a horse, a cow, everything they needed. Nastasya was a hard worker, the children were good and obedient, so they'd little to fret them.

They went on like that for a year, and another, and a third, and then they found they were getting a bit poorer. After all, you couldn't expect a woman with small children to farm real well. And they needed a bit of money now and then, too. To buy salt and such like.

Then Stepan's family started pestering Nastasya: "Sell the casket. What d'ye want with it? There's all those jewels just lying there doing no good. After all, Tanyushka'll never wear them. Things like that! It's only gentry and merchants buy such like. You can't put them on with our poor clothes. And you could get money for them. It'd give ye a bit of a lift up."

They kept nagging and nagging at her like that. And buyers flocked like crows to a bone, merchants all of them. One offered a hundred rubles, another two hundred.

"We're sorry for your children," they said, "we're being kind to ye because you're a poor widow."

They thought they'd got hold of a simple village woman they could fool, but they'd caught the wrong bird.

Nastasya minded what that old foreman had told her, not to let the casket go for naught. And she wais loth to part with it, too. After all, it was a gift from Stepan, her dead husband. And then again, there was her little girl, the youngest child. She kept begging and crying: "Mummie, don't sell it! Don't sell it, Mummie! I'll go out and work, I'll be a servant, but keep it for Father's sake!"

Now, Stepan had left three children. Two were boys, just lads like any others. But the girl, she wasn't like her mother or her father either. Even when Stepan was alive and she was just a babe, folks wondered at her. And not just the maids and wives, but the men too. "Where've ye got her from, Stepan?" they'd say. "Who does she take after? All jimp and pretty, with her dark hair, and then those green eyes! Not like the other maids round our way.''

Stepan would turn it off with a joke. "Naught to wonder at if she's black-haired, with her father working underground since he was a little lad. And green eyes—naught strange there either, with all the malachite I've brought up for our Master Turchaninov. I've got her for a remembrance."

So he started calling her Remembrance; when he wanted her he'd say: "Come here, my little Remembrance!" And when he bought something for her, it was always green or blue.

Well, the child grew, and all took note of her. She was like a bright bead dropped from a gay necklace—she stood out, like. And though she wasn't a child to make friends with folks, they all smiled at her. Even cross-grained shrews had a good word to say. A real beauty, she wais, everyone liked to look at her. Only her mother sighed.

"Beauty, aye, but not our kind of beauty. Like a changeling."

She took it real hard when Stepan died. She got thin, seemed to waste away till she was nothing but eyes. So one day her mother got the idea of giving her the malachite casket to let her amuse herself with the things in it. She might be little but still she was a maid, even when they're children they like to adorn themselves. So Tanyushka tried on this and that, and it was a wonder, whatever she put on, you'd have thought it was made for her. Some of the things, her mother didn't even know what they were for, but she seemed to know everything. And that wasn't all. She kept on saying: "Oh, Mummie, I feel so nice in Father's presents, they're all warm, it's like sitting in the sun and somebody stroking you very, very softly."

Now, Nastasya had worn them, and she hadn't forgotten how her fingers had got swollen and her ears had hurt and the necklace had been icy cold. And she thought to herself: There's something queer here. Uncanny, it is. So she put the casket away in the chest again. But after that Tanyushka was always at her with "Mummie, let me play with Father's presents."

Nastasya wanted to deny her, but she hadn't the heart, so she'd get out the casket, and only warned the child: "See ye don't break aught."

When Tanyushka was a bit older she'd get out the casket for herself. Nastasya would take the lads to mow or some other work and leave Tanyushka to mind the house. First, of course, she'd get through the jobs her mother had left her—wash the dishes, shake out the tablecloth, sweep up, feed the hens and see the fire was all right. She'd hurry up and finish, and then get out the casket. There was only one chest left now on top of the bottom one, and it had got real light at that. So Tanyushka could easily move it on to a stool and get the casket out of the bottom chest. Then she'd take out the trinkets, and start trying them on.

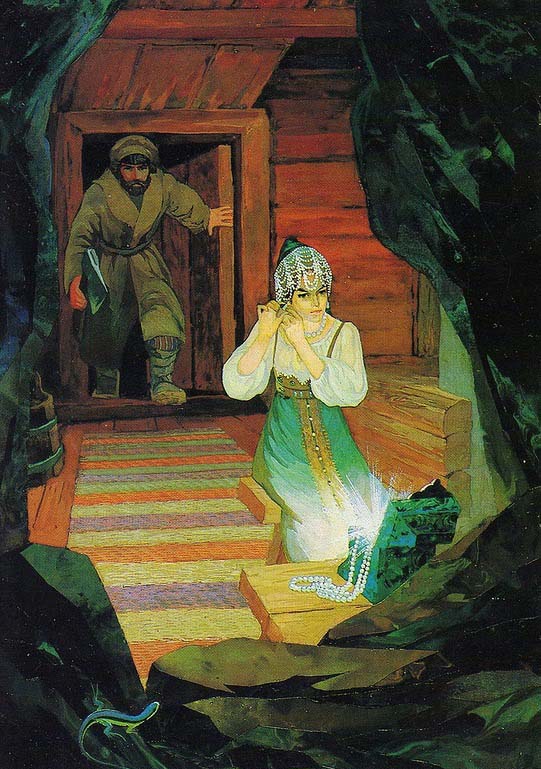

One day a robber came when she was busy with them. Maybe he'd hidden in the garden early, or maybe he'd slipped in some way, for none of the neighbours saw him in the street. He was a stranger, but it looked as if someone had told him everything, when to come and how.

After Nastasya left, Tanyushka did a few bits of work outside, and went into the house to get the casket. She put on the jewelled head-dress and the earrings. And that was when the robber slipped in. Tanyushka looked round and there stood a man she'd never seen before, with an axe in his hand. It was their own axe, it had been standing in the entry. She had put it in the corner herself after sweeping up. Tanyushka was frightened all right, she just sat there, but that man, he cried out and dropped the axe and clapped both hands over his eyes as if they burned him. "Oh, I'm blinded, oh Heavens, I'm blinded," he groaned and kept rubbing his eyes.

Tanyushka saw something had happened to him, so she plucked up courage.

"What have ye come for," she asked, "and why have ye got our axe?"

But that man, he just groaned and kept rubbing his eyes. Tanyushka began to feel sorry for him, she got a mug of water and wanted to give it him, but he stumbled to the door and yelled: "Keep off!"

He backed into the entry and stopped there, and held the door so Tanyushka couldn't get out. But she climbed through the window and ran to the neighbours. Well, they came with her and started asking the man who he was and what he wanted. He blinked a bit, he was beginning to see again, and then said he'd been passing and come to ask alms, and then something had happened to his eyes.

"It was like the sun in them, I thought I was blinded. Maybe the heat made me sick."

Now, Tanyushka hadn't told the neighbours about the axe or the casket either. So they said to each other: "It's naught, she maybe forgot to fasten the gate and he came in, and then something happened to him. All sorts of things happen."

Still, they kept him there and waited for Nastasya. When she came with the boys the man told her the same as he'd told the neighbours. Nastasya saw everything was in its place, nothing gone, so she didn't bother about him. The man went away and the neighbours too.

Then Tanyushka told her mother all about how it really had been. Nastasya guessed he'd come for the casket, but it seemed it wasn't such an easy thing to steal it. All the same, she thought, I'd better be careful.

She said nothing to Tanyushka and the other children, but she took the casket into the cellar and shovelled earth over it.

Again they all went out and left Tanyushka alone. She wanted to get the casket, but it wasn't there. Tanyushka was real upset, but suddenly she felt something warm about her. What could it be? Where did it come from? She looked round and saw a light coming up through the cracks of the floor. That frightened her—was something on fire down there? She opened the trapdoor and looked down—yes, there was a light coming from one corner. She got a bucket of water to put out the fire, but she couldn't see anything burning and there wasn't any smell of smoke either. So she felt about in the loose soil where the light was coming from and there she found the casket. She opened it and the stones seemed even more beautiful than they had been before. They were all sparkling in different colours and a light came from them like from the sun. Tanyushka did not take the casket up into the room, she stopped where she was and played with the trinkets till she was tired.

So it went on from that day. The mother thought: I've hidden it well, no one knows where it is... And the daughter, as soon as she was all alone, would spend am hour or so playing with her father's presents. As for selling them Nastasya wouldn't listen to a word about it.

"If it looks like we'll have to go and beg our bread, then I'll do it, but not before."

She had a hard time, but she stuck to it. She struggled through a few years and then things got better. The older children started to earn a bit, and Tanyushka wasn't idle, either. She learned to embroider with beads and silk, and she did it so well that the cleverest embroiderers in the gentry's sewing-rooms threw up their hands in amaze—where did she get the designs, and where did she find the silks?

It had been a strange chance, how that had all come about. A woman knocked at the door one day. About Nastasya's age, she was, not very tall, dark, with sharp, keen eyes, and quick enough to take your breath away. She had a homespun bag slung on her back and a cherry-wood staff in her hand like a pilgrim. She came to the door and asked Nastasya: "May I stop and rest a day or two, Mistress? I've a long road ahead and I'm dropping on my feet."

At first Nastasya wondered if it was someone after the casket again, but she let her stay all the same.

"I don't grudge ye a rest," she said. "Ye won't wear a hole in the floor or take it with ye. But it's poor fare here. In the morn it's onions and kvass, in the evening kvass and onions, that's all the change there is. If that'll do for ye, stop as long as ye like, and welcome."

But the traveller had already put down her staff and laid her bag on the seat by the stove without waiting for leave, and was taking off her boots. Nastasya wasn't too pleased at that. Pretty free and easy she is, thought Nastasya, starts taking off her boots and opening her sack without waiting for yea or nay.... But she said no word of it.

Sure enough, the woman was unfastening her sack; then she beckoned Tanyushkai.

"Come here, child, and look at my handiwork. If it pleases ye, I'll teach you to do it too, I can see ye've an eye for it."

Tanyushka went up close, and the woman gave her a strip of cloth with both ends embroidered in silk. And it was such a brilliant pattern, the very room seemed the brighter and warmer for it.

Tanyushka couldn't stop looking at it, and the woman laughed. "So it takes your eye, my work, does it?" she said. "Would you like me to teach it ye?"

"I would!"

But Nastasya snapped: "Don't ye even think of it. We've no money to buy salt with, and ye want to do silk embroidering! Silk costs money."

"Don't fret yourself about that, Mistress," said the traveller. "If your daughter has skill she'll have the silk too. For your kindness I'll leave her enough to last a while. And after that ye'll see how it'll be. Folks pay money for our craft. We don't give our work away. We earn our bread."

So Nastasya had to agree.

"If ye'll give her the silk, she can learn well enough. Why not, if she can do it? And thank ye kindly."

So the woman started to teach Tanyushka and the maid learned it all as quick as if she'd known it before. And there was another thing. Tanyushka wasn't friendly with strangers, or loving with her family either, but this woman—she was clinging to her all the time. Nastasya looked askance, she wasn't too pleased. Found herself a new mother, she thought. Doesn't want to come to her own mother, but hugs a tramp!

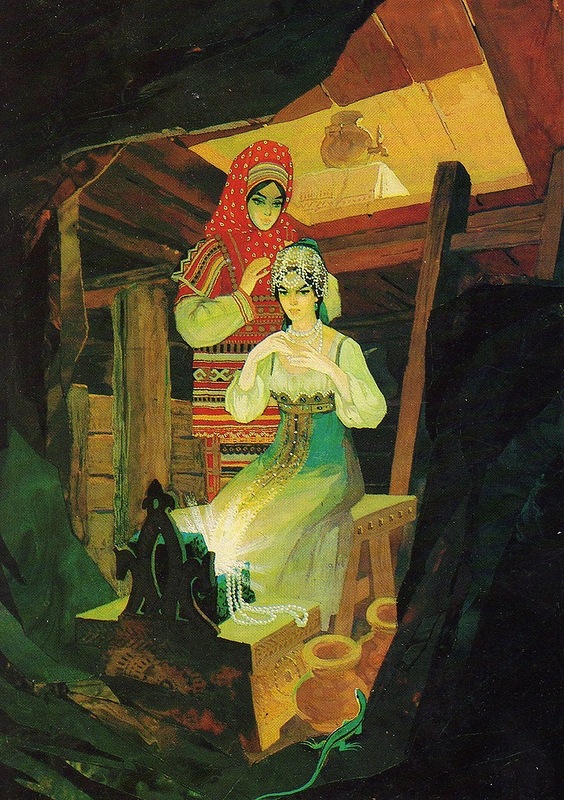

And that woman, just as though she wanted to rub it in, kept calling Tanyushka "child" and "daughter," and never once used her christened name. Tanyushka saw her mother was put out, but it seemed like she couldn't help herself. She was so taken up with the woman, she even told her about the casket.

"We've got a costly remembrance of Father," she said, "a malachite casket. And the stones in it! I could look and look at them and never tire."

"Will you show it me, Daughter?" asked the woman.

It never even came into Tamyushka's head that she mustn't.

"Aye, I'll show ye," she said, "when there's none of ours at home."

As soon as the chance came, Tanyushka took the woman down in the cellar. She got out the casket and opened it; the woman looked a bit, then she said: "Put them on, I can see them better that way."

Tanyushka didn't need telling twice, she put them on, and the woman, she started praising them.

"Aye, they look fine, but they just need a touch or two."

She came up close and started touching a stone here and a stone there with her finger. And whatever stone she touched, it sparkled quite differently. Tanyushka could see some of them, and some she couldn't. Then the woman said: "Stand up straight, Daughter."

Tanyushka stood straight, and the woman started stroking her hair and her back, very gently. She stroked her all over, then she said: "When I tell you to turn round, mind you don't look back at me. Look straight in front, watch all you see and say naught. Now turn round."

Author: Bazhov P.; illustrated by Nazaruk V.Please support us

PayPal: anfiskinamama@gmail.com

Contact us if you have any questions or see any mistakes

© 2019-2026 Freebooksforkids.net