|

Free Online Illustrated Books for Kids |

Popular Andersen Fairy Tales Animal Stories Poetry for Kids Short Stories Categories list

P.Bazhov

The Malachite Casket

Translated by Eve Manning

freebooksforkids.net

Illustrated by V.Nazaruk

Tanyushka turned, and there was a great hall in front of her, she'd never seen the like in all her life. It looked like a church, and yet it wasn't quite the same. The ceiling was very high up, supported on columns of pure malachite. The walls were covered with malachite to the height of a man, and there was a pattern of malachite all along the top. And right in front of Tanyushka, like in a mirror, stood a beautiful maiden, the kind you hear of in fairy-tales. Her hair was dark as night and her eyes shone green. She was decked with precious stones, and her robe was of green velvet that gleamed all shades. It was a robe made like the ones worn by tsarinas in pictures, you wonder what keeps them up. Our maids would take shame to let folks see them like that, but the green-eyed maid stood there quite quiet, as if that was the proper way. And that hall was full of people, dressed city way, all gold and medals. Some had medals hanging in front, others had them sewn on the back, and some had them all over. It was clear they were very great lords. And there were women, too, just the same with naked arms and naked bosoms and jewels hung all over them. But none could hold a candle to the green-eyed maid. Not one of them worth a look, even.

Beside the maid stood a tow-headed man; he'd a squint and big ears that stood out, so he looked for all the world like a hare. And the clothes he wore—a fair wonder, it was. Gold wasn't enough for him, he'd got precious stones on his shoes, even. And the kind you'd find once in ten years. He must have had a lot of mines of his own. He kept babbling something to the maid, that hare did, but she didn't so much as move an eyebrow, just as if he wasn't there.

Tanyushka looked at the maid, wondered at her, and then she suddenly noticed something. "Why, those are Father's stones she's wearing!" she cried, and in that moment it all vanished.

The woman just laughed.

"You didn't look long enough, Daughter! Now don't ye fret, you'll see it again, all in good time."

Of course Tanyushka was full of questions—where was that place she'd seen?

"It's in the Tsar's palace," said the woman, "it's the hall that's decorated with the malachite your father got."

"And who was that maid wi' Father's gems and who was the man as looked like a hare?"

"That, my child, I'll not tell ye, you'll soon learn it for yourself."

When Nastasya came home that day, the stranger woman was getting ready to go. She bowed low to the mistress and gave Tanyushka a bundle of silks and beads. Then she took out a little button, it might have been glass or it might have been crystal cut smooth.

"Take this, Daughter, for a remembrance," she said, and gave it to Tanyushka. "If you forget something in your work, or if you're in a difficulty, look at the button. You'll find your answer there."

With that she turned and went away. Vanished all of a sudden.

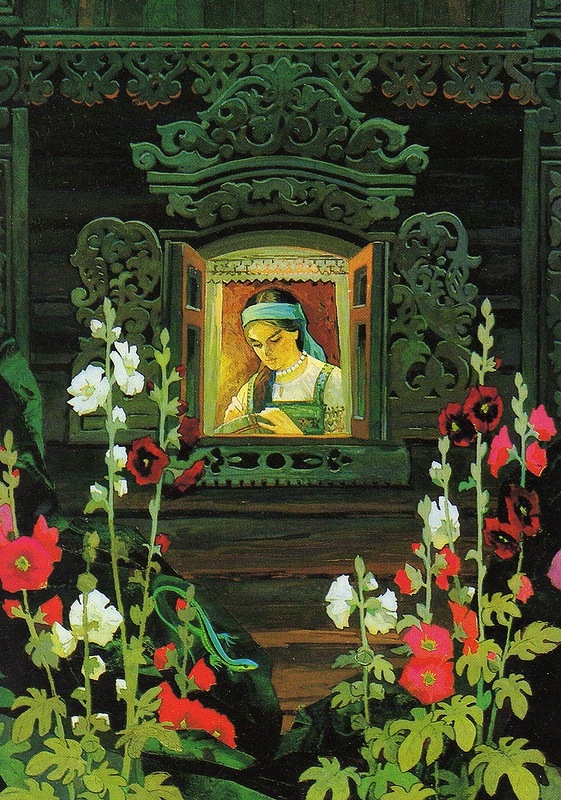

From then on Tanyushka was skilled at her craft. She was coming to the age for marriage, too—she looked a grown maid already; the lads would eye Nastasya's window, but they didn't dare to make free with Tanyushka. She wasn't the friendly sort, you see, she was grave and aloof. And besides, what would a free maid want with a serf? It would be just putting her head in the yoke.

In the Big House they heard of Tanyushka's skill at her craft, and started sending lads to her. They'd pick one of the lackeys, one that was young and handsome, give him a fine suit, hang a watch and chain on him and send him to Tanyushka with some message or other. Maybe, they thought, a dashing young fellow like that would catch her fancy. Then they'd have her a serf. But it was no good. When the lackey gave his message she would answer him, but for all other talk she had no ear. And when she got tired of it she'd make a mock of him too.

"Go along, go along, they're waiting for ye. They must be feared you'll spoil that fine watch and rub the gold off the chain. Can't keep your fingers off it, it's that new to ye."

She'd got words that scalded like hot water thrown on a dog. He'd slink off snarling: "Call that a maid? A stone statue with green eyes! There's plenty better!"

He could snarl all he liked, but still he'd seem bewitched, like. Whoever they sent was mazed with Tanyushka's beauty. Something seemed to pull them back, even though it was only to walk past and eye the window. On feast days all the young fellows in the village found something to do in that street. They beat a track past the window, but Tanyushka never so much as looked at them.

The neighbours began to reproach Nastasya.

"Who does she think she is, your Tanyushka? She keeps away from the girls and she won't look at the lads. Is she waiting for the Tsarevich, or does she think to be the Bride of Christ?"

Nastasya could only sigh.

"Eh, Neighbour, I can't make aught of it myself. She always was a strange maid, but since that sorceress was here, she's beyond me. I start talking to her, and she just stares at that witching button of hers and says no word. I'd throw it away, that button, but it helps her in her work. When she needs to change her silks and that, she looks at the button. She showed it me once, but my eyes must be getting bad for I saw naught there. I could give her a whipping, but she's a right good worker. It's really her craft as keeps us. So I think and think till I start crying. And then she says: 'But Mother, I know this won't always be my place. I don't beguile the lads, I don't even join the games. Why should I want to plague folks for naught? If I sit by the window it's because I have to, for my work. Why d'ye scold me? What have I done bad?' Now how can I answer that?"

But with it all, life was better for them. Tanyushka's work got to be the fashion with the gentry. It wasn't only the ones near the village and in our town that bought it, people sent from other places too, and paid well for the work. Many a good man doesn't earn as much. But then there came a great mishap—a fire. It broke out in the night. The sheds and shelters for the livestock, the horse and cow, the farm tools and other gear—all were lost. They just managed to get out with what they stood up in. Except that Nastasya did snatch up the casket.

The next day she said: "Seems like we've come to the end. We'll have to sell the casket of gems." And the sons all said: "Aye, sell it, Mother. But don't let them go cheap."

Tanyushka looked secretly at the button, and there was the green-eyed maid nodding—aye, sell them. It was a bitter thing for Tanyushka, but there was naught else to be done. Besides, soon or late they would go to that green-eyed maid anyway. So she sighed and said: "Aye, sell them if ye must." She didn't even take a last look at the gems. Besides, they had taken shelter with a neighbour, so there was no place to lay them out.

No sooner had they made up their minds to sell, than the merchants were there. Maybe one of them had started the fire himself so as to get hold of the casket. They're that sort—got claws that'll pierce aught to grab what they want. They saw the lads were grown now, so they started offering more. Some five hundred, and one even went up to a thousand. There was plenty of money about, Nastasya could set herself up quite comfortable with those gems. Well, so she asked two thousand. They kept coming to her, bargaining; they'd raise their prices a bit and keep it from each other, for they never could agree among themselves. It was a tempting bit, you see, that casket, none of them wanted to lose it. And while they were still at it, a new bailiff came to Polevaya.

There were times when bailiffs stopped a long while, but in those years they kept changing and changing. The Stinking Goat who was there in Stepan's days maybe got to stink too much even for the old Master's stomach, anyway, he was sent to Krylatovskoye. Then came Roasted Bottom—the workers sat him down on a hot ingot one day. After him there was Severyan the Butcher, the Mistress settled him, turned him into rock. Then there were two more, and at last the one I'm going to tell you about.

Folks said he was from foreign parts and knew all sorts of languages, all but our Russian, he spoke that badly. But there was one thing he could say well enough: "Flog him!" He'd draw it out, like, as though he was singing: "Flo-o-o-og him!" Like that. And whatever a man had done, it was always the same: "Flo-o-og him!" So folks called him Flogger.

That Flogger wasn't really so bad, though. He made a lot of noise, but he didn't use the whipping post very much. The tormentors got fat and lazy, they'd naught to do. Folks had a chance to breathe a bit when Flogger was there.

You see, it was this way. The Old Master had grown feeble, he could ,hardly get about. And he wanted to marry his son to a countess or someone like that. But the young gentleman had a kept woman and he was real foolish over her. There it was, a puzzle for the Old Master. It was kind of awkward. What would the bride's parents say to it? So the Old Master began persuading that woman—his son's light o' love—to marry the music teacher. The Old Master had one there to learn the children music and foreign tongues, the way the gentry did.

"Why go on living wi' a bad name?" he said. "Marry the music teacher. I'll give ye a good portion and send your husband to be bailiff in Polevaya. It's all plain and easy there, so long as he's strict wi' the folks. He ought to have sense enough for that, even if he is a musician. And you'll live real well, you'll be the lady of the place. You'll be respected and honoured and all the rest of it. Naught wrong wi' that, is there?"

The woman was ready to listen. Maybe she'd quarrelled with the Young Master, or maybe she was just clever.

"It's what I've been wanting a long time," she said, "but I didn't like to ask."

As for the music teacher, well, of course he jibbed at first. "I don't want her," he said. "She's got a bad name, she's a trollop."

But the Old Master was sly. That's how he'd got rich. And he turned that music teacher right round. Whether he scared him or flattered him or got him drunk I don't know, but he soon had the wedding day fixed and then the young couple went off to Polevaya. That was how Flogger came to our village. He didn't stop long but—give him his due—he wasn't so bad. Afterwards, when they got Double Jowl instead, folks wished him back.

Flogger and his dame came just at the time when the merchants were round Nastasya like flies round a pot of honey. Now, that woman of Flogger's was a handsome piece, all pink and white—a real light o' love. Trust the Young Master to pick a tasty bit! Well, this fine lady heard about the casket. "Let's have a look at it," she said, "maybe it's really worth buying." So she dressed herself up and drove to Nastasya. They had all the estate horses to use.

"Here, my good woman," she said, "show me those stones you're selling."

Nastasya got out the casket and opened it. And Flogger's dame—her eyes nearly popped out of her head. She'd lived in Petersburg, and been in other lands with the Young Master too, and she knew something about gems. And she was real amazed. What's this, she thought, the Tsarina hasn't gems like these, and here they are in Polevaya, with folks as have been burnt out! I must see they don't slip through my fingers.

"What d'ye want for them?" she asked, and Nastasya told her: "I'm asking two thousand."

The dame bargained a bit, just for decency's sake, then she said: "Well, I'll give ye your price, my good woman. Bring the casket to my house, and you'll get your money there."

But Nastasya told her: "Bread doesn't run after a stomach in our parts. Bring the money and the casket's yours."

Well, Flogger's dame saw she'd have to do it the way Nastasya wanted. So she hurried home for the money. But first she told Nastasya: "See you don't sell to anyone else."

"Don't ye fret," said Nastasya. "I keep my word. I'll wait till evening, but after that I do as I like."

Off went the dame, and all the merchants came hurrying in, they'd been watching, you see. And they wanted to know what had happened.

"I've sold them," said Nastasya.

"How much?"

"Two thousand, the price I asked."

Then they all shouted at her: "Are you crazy or what? Give them to a stranger and refuse your own folk!" And they started bidding again, putting up their prices. But Nastasya wasn't to be caught.

"Those may be your ways, say this and promise that and turn it all round, but they're not mine. I've given my word, and that's the end of it."

Flogger's dame was soon back. She brought the money, put it into Nastasya's hand, picked up the casket and turned round to go back home. And there on the threshold she met Tanyushka, the maid had been away somewhere when the casket was sold. Tanyushka saw the dame holding the casket and looked well at her, but it wasn't the one she'd seen that time. And Flogger's wife stared back.

"What's this sprite? Whose is she?"

"Folks call her my daughter," said Nastasya. "It ought to have gone down to her, that casket you've bought. I'd never ha' sold it if we hadn't got to the end. Ever since she was a bit of a thing she's always played wi' those gems. She'd try them on and say they made her feel warm and happy. But what's the good, talking o' that now? What falls off the cart's lost and gone!"

"You're wrong there, my good woman," said Flogger's dame. "I'll find a place for those gems, they won't be lost." But what she thought to herself was: A good thing that green-eyed maid doesn't know her own power. If she got to St. Petersburg she'd turn the heads of tsars. Better see my fool Turchaninov doesn't set eyes on her.

On that they parted.

Flogger's wife came home and started to brag to her husband.

"Now, my friend, I don't need to be beholden any more to you or to Turchaninov either. The first thing that doesn't suit me—off I go! I'll go to St. Petersburg, or maybe I'll go abroad, I'll sell the casket and then I'll buy husbands like you by the dozen if I want."

That's how she bragged, but all the same she badly wanted to show herself in those gems she'd bought. A woman, after all! So she ran to the mirror and first of all she put on the head-dress. But—oh, oh, what's this? It nipped her and pulled her hair so she just couldn't bear it. And she had a job to get it off. But still she itched to see herself in the things. She put on the earrings and they nearly tore her lobes. She put on a ring and it nipped so she could hardly pull it from her finger, even when she soaped it. And her husband just sat and jeered at her—not meant for you to wear, those things!

It's queer, she thought. I'll have to go to town and let a good craftsman take a look at them. Shape them and make them fit—but I must see he doesn't change the stones.

No sooner said than done. The next morning off she went. It didn't take long to get to town with three good horses pulling. She asked folks where she could find a good craftsman and an honest one, and sought him out. He was an old man, real ancient, and very skilled. He took a look at the casket and asked her where she'd bought it. The dame told him all she knew. The old man looked at the casket again, but he never even glanced at the gems.

"I won't touch them," he said, "no matter what ye offer me. The craftsmen that made all this are none of ours. And I'm not the one to vie with them."

Of course the dame didn't understand what it was all about, she sniffed and went off to find another craftsman. But it was as if they were all in a plot. One after another they looked at the casket, admired it, never so much as glanced at the gems and refused to have anything to do with it. Then the dame tried cunning, she said she'd bought the casket in St. Petersburg. There were plenty like it there. But the man she served with that tale only laughed at her.

"I know where the casket was made," he said, "and I've heard tell of the craftsman that made it. There's none of us can try to vie with him. If he's made things to fit one, no other'll be able to wear them, try as ye will."

The dame still didn't understand the whole of it, but one thing she could see—the man was scared of something. And then she called to mind how Nastasya had said her daughter liked to put on those trinkets.

Could they be made for that green-eyed creature? Bad fortune, indeed!

But then came second thoughts. What does it matter to me? I'll sell them to some rich fool. Let her bother herself about them, the money'll be safe in my pocket!... So back she went to Polevaya.

When she arrived she found news. The Old Master had gone to his eternal rest. He'd been cunning enough, the way he'd fixed it all with Flogger, but Death had been one too many for him. Knocked him over the head. He hadn't had time to get his son married, so now the young man was his own master. And it wasn't long before Flogger's wife got a letter. It told her this and that, and when the spring floods go down, my sweeting, I'll come and have a look at the village and take you back with me, and as for your music master, we'll get rid of him somehow... Flogger found out about it and made an uproar. It shamed him before the folks. After all, he was the bailiff, and now here was the Master coming to take away his wife. He started drinking hard. With the clerks and such like, of course. And they, were glad enough so long as he stood treat.

One day when he was carousing with his flatterers and boon companions, one of them started to brag.

"We've got a real beauty in our village, you'd have to go a long journey to find another like her."

Flogger was quick enough to catch that. "Whose maid is she? Where does she live?"

They told him all about it, and reminded him of the casket—that's where your goodwife bought it, from that family.

"I'd like to take a look at her," said Flogger, and the carousing band thought of a way to do it.

"We can go now, see if they've built the new cottage right. They're free, but they live on the village land. There's always ways to compel them."

Off they went, two or three of them, and Flogger too. They took a chain for measuring, to see if maybe Nastasya had filched a bit of land from the neighbours, and if the boundary posts were the right distance apart. Tried to catch her out. Then they went into the cottage, and Tanyushka happened to be alone there. Flogger took one look at her and lost his tongue. For he'd never seen such beauty in any land he'd been in. He just stood there like a fool, and as for her—she sat quite quiet as though it was all naught to her. Then Flogger got his wits back a bit and asked her: "What's that you're doing?"

"It's embroidery folks have ordered," she said, and showed him.

"And would ye take an order from me?" asked Flogger.

"Why not, if we come to terms."

"Then," said Flogger, "can ye make me a portrait of yourself in fine silk?"

Tanyushka looked quietly at her button, and the green-eyed maid signed to her—take the order, and then pointed at herself.

"I won't make my own portrait," said Tanyushka, "but I know a woman wearing precious gems, in the robe of a tsarina, I can do that. But it won't be cheap, such work."

"Ye needn't fret about that," said Flogger, "it can be a hundred rubles or two hundred, if only the woman's like you."

"The face'll be like," she said, "but the clothes will be different."

They agreed on a hundred rubles. Tanyushka said it would be ready in a month. But all the same Flogger kept coming and coming, making as though he wanted to see how it was getting on, but it was something quite different really. His wits seemed turned, but Tanyushka, she took no notice. She'd say two or three words, and that was all. Flogger's boon companions started to mock him.

"You'll get naught there. Wasting boot leather!"

Well, Tanyushka finished that portrait. Flogger took a look and—God above!—it was her very self, only in rich robes and gems. He gave her three hundred rubles instead of one, but Tanyushka handed two of them back.

"We don't take gifts," she said, "we work for our bread."

Flogger hurried home; he kept looking at that portrait but he hid it away from his wife. He didn't drink so much, and started to take a bit of interest in the village and the mine.

Please support us

PayPal: anfiskinamama@gmail.com

Contact us if you have any questions or see any mistakes

© 2019-2026 Freebooksforkids.net