|

Free Online Illustrated Books for Kids |

Popular Andersen Fairy Tales Animal Stories Poetry for Kids Short Stories Categories list

P.Bazhov

The Magic Gem

Translated by Eve Manning

freebooksforkids.net

Illustrated by L.Panova

Seeking gems is a trade I've never had much liking for. I've found them, at times, but just by chance. You happen to be looking at pebbles washed down and you see something sparkling. Well, you pick it up and show it to someone with knowledge of those things—shall I keep it or throw it away?

With gold, now, it's simple. Of course there's different kinds with that too, some better, some worse; but it's not like those stones. With them neither size nor weight have any meaning. You can have a big one and a small one, they both shine the same, but when they're tested you find they're different. And for the big one folks won't give a copper, while they're all eager after the little one—amazing water, they say, it'll have the real fire.

There's times it's queerer still. They'll buy a stone from you and right there you watch them chip off half of it and throw it away. "That only spoils it," they'll say, "it dims the fire." And then they'll grind off half of what's left, and sing the praises of it too—"There's the pure water, now it'll sparkle so it'll shams the lamps!" And it's right, the stone'll end up tiny, but as if it was alive and laughing. But what it costs—that's no laughing matter, you hear it and gasp. Nay, I can make naught of those things.

But all that talk about stones that keep you from sickness, and stones that guard you when you're sleeping, or keep sorrow away and all the rest of it, that's just idle chatter to my mind, naught else. Though there is one tale about stones I heard from my old folks that took my fancy. It's a nut with a good kernel, for those with sound teeth to crack it.

They say there's a stone somewhere under the ground, and no other like it anywhere, it's the only one. None have ever found that stone. Not just in our land, but in other lands too, but the word of it's known all over. And the stone is under our soil. The old folks found that out. No one knows the spot where it is, but that's no matter, for the stone will come itself to the hand of the right one. That's another thing special about it. Folks learned it all from a young maid. This is the way they say it was.

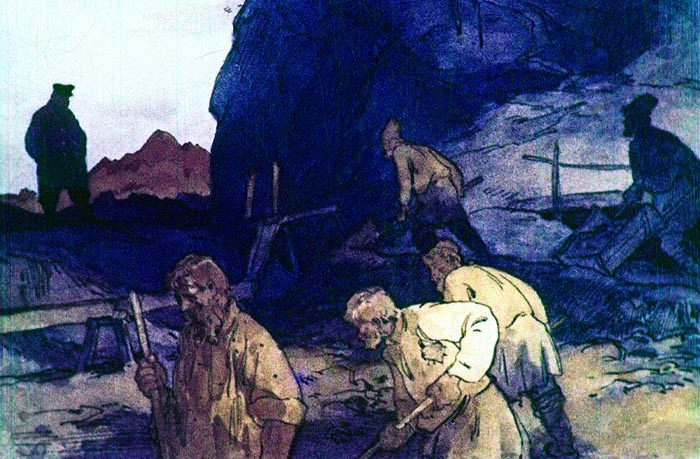

Near Murzinka, or maybe it was some other place, there was a big ore mine. They found gold and all sorts of gems there.

It was Crown land, those days. And the officials with their bright buttons—butchers in uniform, they were—used to drive folks to work with beat o' drum, and drum them through the lines running the gauntlet, with stripes raining down on them. A real place of torment, it was.

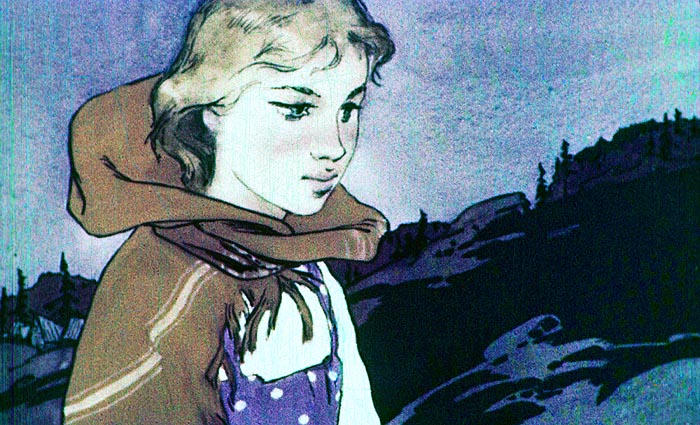

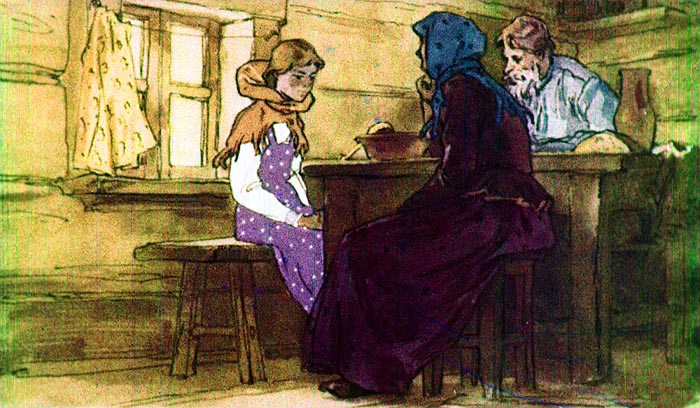

In the midst of it all was that little girl, Vasenka. She was born at the mine and she lived there, summer and winter. Her mother was a sort of cook at the barrack where the foremen lived; as for her father, Vasenka knew naught of him.

No need to tell you the sort of life children of that kind lived. Men had to hold their tongues under all the torment, but then it would get too much for them and then they'd curse her or clout her over the head because they had to let it out on someone. Aye, it was a bitter life she had. Worse than an orphan's. And there was none could save her from being put to work early, either. A child, with hands hardly strong enough to hold the reins, and she was put to carting. "Carry sand instead of getting under folks' feet!"

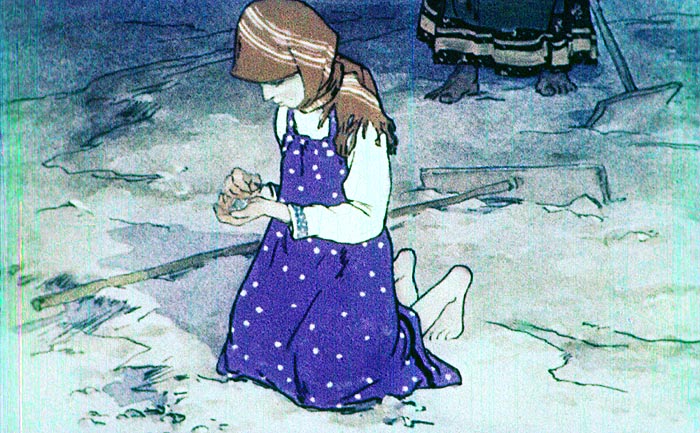

As soon as she grew a bit bigger she was given a board and sent off with the other maids and women to search the sand for gems.

And then they found Vasenka had a real knack for it. She found more than any others, and all good ones, really valuable.

She was a simple-hearted maid, what she found she handed in at once to those over her. And glad they were, of course. Some they put in the bank, some in their pockets and some in their cheek. You know the old saying—what a big man puts in his pocket a little one has to hide. And one and all praised Vasenka as though they'd chosen the words together. They gave her a nickname too—Lucky Eye. As soon as one of them came along he'd make straight for Vasenka.

"Well, Lucky Eye, have you something worth looking at?"

Vasenka would give him what she had, and he'd gobble away like a goose. "Good, good, go-o-od! Seek well, my girl, seek well!"

Vasenka did seek, for she liked doing it.

Once she found a stone the size of her thumb and all the big folk came running to take a look. So that time no one could steal it, they had to send it to the bank. And after, folks say, it was taken from the Tsar's treasury to some foreign land. But that's not what I wanted to tell you.

Vasenka's luck made it worse for the other women and maids, the foremen never let them alone.

"Why can she find all those, and you bring us rubbish and little of that? You seek with only half a heart."

Instead of giving Vasenka good counsel the women banded together in spite against her. And her life wasn't worth living.

And then a cur came slavering round, the chief foreman. He'd a nose for Vasenka's good fortune, so he said: "I'll wed that maid."

His teeth had all rotted away long before and on top of that you couldn't come within five paces of him for the stench, as if he'd rotted away inside too. And he kept snuffling: "I'll make a lady of ye, my maid. Mind that, and the stones you find give to me and to no one else. Don't let others even see them."

Vasenka was tall but she wasn't near the age to wed. She might have been thirteen, or fourteen maybe. But who'd pay heed to that if it was the foreman? The priest would write any age in the book. Well, Vasenka was real scared. Her hands shook and her legs too when she saw that rotting suiter. She'd make haste to give him all she'd found, and he'd keep rumbling: "Seek well, Vasenka, seek well! Come winter, you'll be sleeping in a feather bed."

As soon as he's gone the women would start jibing and jeering at Vasenka, and she was ready to tear herself to bits as it was, if she'd been able. After the evening drum she'd run to her mother in the barrack, but that only made it all worse. The mother was sorry for her, of course, tried to protect her all she could, but what could the barrack cook do when it was the chief foreman? He could hale her to the flogging post any day he wanted.

Vasenka managed to hold him off till winter, but she could do no more. He started coming to her mother every day.

"Give me the maid wi' good will, or it'll be the worse for ye."

No use saying the maid was too young to wed, he'd push that paper from the priest under her nose.

"Will you try to lie to me! The church book says she's sixteen. The lawful age. Better not cross me more, or I'll have ye to the whipping post tomorrow."

So the mother had to give way.

"Seems it's your fate, Daughter, and you can't escape it."

And the maid? Her arms and legs went weak, and not a word could she say. But by nightfall it passed over and she ran away from the mine. She didn't even take any special care, she just went straight off down the road, but where that road led she never even thought. All she wanted was to get as far away as she could.

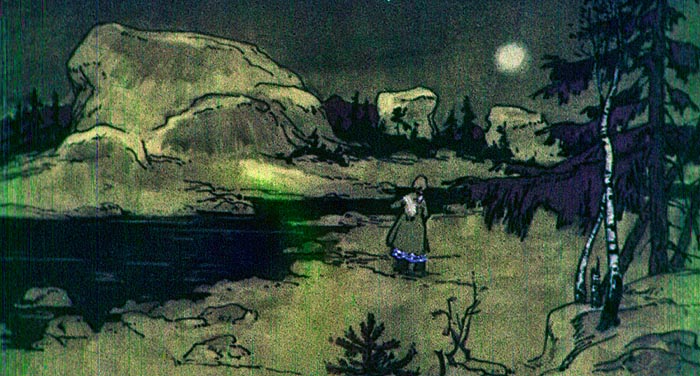

The weather was warm with no wind, and at eve snow began to fall. Gentle flakes like little feathers. The road took her into the forest. There'd be wolves and other wild animals, but Vasenka didn't fear them. She'd made up her mind.

"Better be eaten by wolves than wed stinking offal."

So on and on she went. At first she stepped out bravely. She covered fifteen versts or maybe twenty. Her clothes weren't much to speak of but she wasn't cold, she even felt hot. The snow was deep, up to her knees, she could hardly plough through it, and that warmed her. And it kept on falling, thicker than ever, a real mass of it. Vasenka got tired at last, she felt she couldn't go another step, so she sat down by the roadside.

I'll rest a bit, she thought—she didn't know it's the worst thing you can do, to sit down in an open place in weather like that.

She sat there looking at the snow, and it kept on falling and clung to her. After she'd sat a bit she felt she just couldn't get up. But she wasn't afraid, she just thought: I'll have to sit a bit longer, rest myself properly.

Well, she rested. The snow covered her right up, she was like a shock of hay standing by the road. And there was a village near.

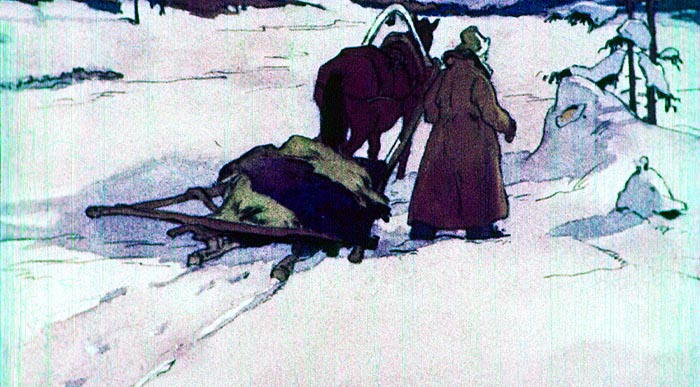

By good fortune one of the villagers came by in the morning—in summer time he used to seek gold, and stones too. Well, he came by with a horse and sledge, and the horse stopped and snorted and didn't want to go near that shock. Then the man took a look and saw it was some person buried in snow.

He went up close and found the body wasn't frozen through, he could bend the arms. So he put Vasenka on the sledge, covered her with his sheepskin and off home with her. Then he and his wife set to work to thaw her and bring her to life again. And they managed it. She opened her eyes and her fingers loosened. And there in one hand lay a great shining stone, pure blue water. The man was really scared when he saw it, a thing like that could take you to jail, so he asked: "Where did you get that?"

"It flew into my hand by itself," said Vasenka.

"What? How—?"

So Vasenka told him all about it.

When the snow began to cover her right up, a passage into the earth suddenly opened in front of her. It wasn't very wide and it was dark too, but you could go along it. She could see steps, and it was warm. Vasenka was glad. None from the mines will ever find me here, she thought, and went down the steps.

She went on for a long time till she came to a great field, so big there seemed no end to it. The grass grew in tufts and there were a few bushes scattered about, all of them yellow as they are in autumn. A river ran across the middle, and it was smooth and black with never a ripple as though it were black stone. On the other side, just opposite Vasenka, was a little mound and on top of it a big stone like a table and smaller ones round it like stools. But not the size folks use, much bigger. It was cold and sort of fearsome there.

Vasenka was just going to turn round and go back when a lot of sparks flew up behind the mound, and when she looked again she saw a pile of precious stones lying on the table. They sparkled all colours, and made the river seem less gloomy too. It was a joy to look at them.

Then somebody asked: "Who are these for?"

From down below came a shout: "For the simple."

The same instant the stones flew away to all sides like a shower of coloured sparks.

Another fiery flicker from behind the mound threw a fresh pile of stones on the table. A lot of them. Enough maybe to fill a hay waggon. And the stones were bigger. Again someone asked: "Who are these for?"

From below came the answer: "For the patient."

Just as before, the stones flew away to all sides. It was as if a swarm of May bugs were flying, only they shone all colours, some glowed red and some were green and there were blue and yellow—all sorts. And they hummed as they flew. While Vasenka was watching those May bugs, the fiery light came up behind the mound again and another pile of stones lay on the table. This time it was quite small, but all the stones were big ones and of great beauty. And the voice from below shouted:

"These are for the daring and for Lucky Eye."

The next moment the stones swooped and flew away to all sides like little birds. They were like tiny lamps swaying over the field. They flew quietly, without haste. And one stone flew to Vasenka and nestled in her hand like a kitten wanting its head stroked—here I am, take me!

With that the light went out and everything vanished.

At first the prospector and his wife were chary of believing her, but then they thought—where could she have got such a stone as that one in her hand! They asked where she came from and who she was, and she told them all about herself, keeping naught back. And she begged them: "Don't let them know back there where I am!"

They thought it over a bit, the man and his wife, and then they said: "All right, stop here and live with us. We'll hide ye somehow, but we'll call ye Fenya. Remember, that's the name you answer to."

Their own daughter had died not long before, you see—Fenya had been her name. And she'd been just the same age as Vasenka. And another thing that would help, the village wasn't on Crown land, it was on the Demidov estate.

So that's how it ended. The Master's Elder marked at once that the maid was new to the place, but what did he care? It wasn't him she'd run away from. An extra pair of working hands was no bad thing. So he just gave her her task with the other folks.

Of course life wasn't all honey on the Demidov estate either, but it wasn't like the Crown mines all the same. And the stone Vasenka had had in her hand helped too. The miner managed to sell it secretly. He didn't get its real price, of course, but all the same he got a good sum. So they were able to live easier for a bit.

When Vasenka was a maid grown she wedded a lad in the village. And with him she lived till she was old, and reared children and grandchildren.

Please support us

PayPal: anfiskinamama@gmail.com

Contact us if you have any questions or see any mistakes

© 2019-2026 Freebooksforkids.net