|

Free Online Illustrated Books for Kids |

Popular Andersen Fairy Tales Animal Stories Poetry for Kids Short Stories Categories list

P.Bazhov

The Blue Crone's Spring

Translated by Eve Manning

freebooksforkids.net

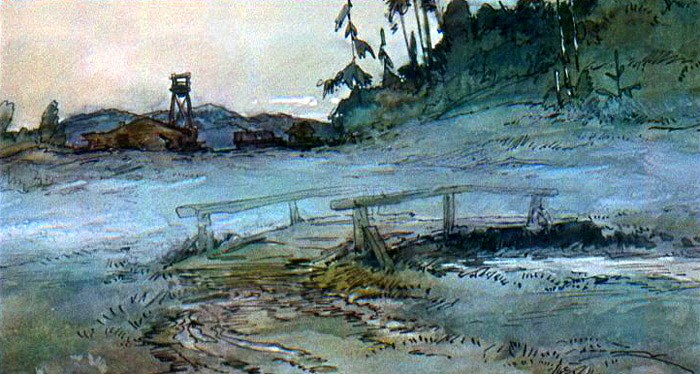

Illustrated by V.Panov

There was once a lad called Ilya in our village. Alone in the world he was, for he'd buried all belonging to him. And each of them had left him something.

From his father he'd shoulders and hands, from his mother sharp teeth and a tongue, from his Grandad Ignat a hack and a spade, and from Granny Lukerya a special remembrance. Let that be told first.

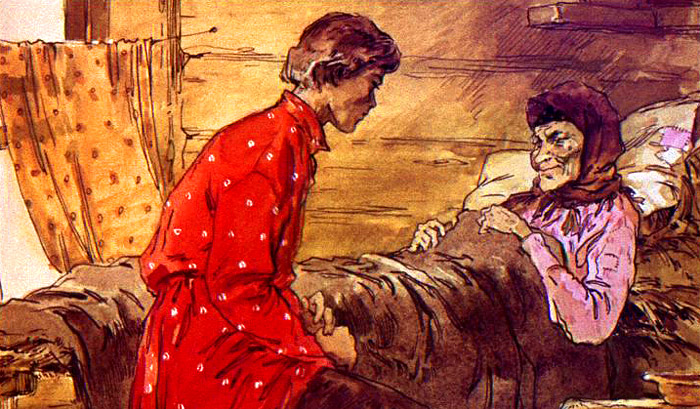

Now—she was real canny, that old woman, she used to pick up feathers in the street and put them by to make a pillow for her grandson, but she didn't have time to finish it. When she felt her end was near, she called Ilya to her.

"Look ye here, Ilya lad, how many feathers your Granny's got together! Nearly a whole sieveful. And what feathers they are—all of a size, little and bright-coloured, a joy to your eye. Take them as a remembrance. They'll come in useful.

"When ye come to wed, if the maid brings a pillow ye'll not be put to shame. Aye, ye can tell her, I've got my own feathers too, my Granny leflt them me.

"But don't ye seek after it, a feather pillow. If she brings one, take it, but if not—don't fret. If ye live with a gay heart and work hard, ye'll sleep sound on straw and your dreams'll be sweet. Keep bad thoughts from your head and all will go well wi' ye. The bright day will cheer ye, the dark night will caress ye and the golden sun will bring ye joy. But if ye let bad thoughts in, then ye might as well smash your head on a tree-stump, for ye'll have no stomach for aught."

"But what are those bad thoughts, Granny?" asked Ilya.

"Thoughts o' money," she said, "thoughts o' wealth; There's none worse. They bring a man only unease and torment. Honest ways'll not even got ye feathers enough for a pillow, so how'll ye ever get wealth?"

"But then," said Ilya, "what about the wealth underground? Will you say that's bad too? Sometimes it happens—"

"Aye, it happens, but it's not to be reckoned on. Comes in grains and goes in dust, and only brings trouble with it. Don't ye think o' that, don't fret yourself. Of the wealth underground, they say there's only one kind that's clean and sure. That's when the Blue Crone turns into a fair maid and gives it ye wi' her own hands. And she gives it to them as have quick wits and daring and a simple heart. None else. So keep in mind, Ilya lad, my last charge to ye."

Then Ilya bowed low to his grandmother.

"Thank you, Granny Lukerya, for the feathers, but thank you most for your teaching. I'll mind it all my days."

His grandmother died soon after. Ilya was all alone, with none elder and none younger. Of course old women came hurrying along to wash the body and lay it out and perform all the rites. It was bitter want sent those old women to corpses. And some would ask for this or that, and others would spy out what they could take. They soon got hold of all Granny had left.

When Ilya came back from the graveyard he found the hut swept bare. He'd naught but what he hung on the nail—his coat and cap. Somebody had even made off with Granny's feathers, emptied the sieve to the bottom. Only three little feathers were left—one white, one black and the third red.

Ilya was grieved that he hadn't been able to take care of his grandmother's gift. I'd better save these last three feathers, at least, he thought. It would be a shame for me to leave them. Granny worked hard to collect them, it's as if I cared nothing for it.

He found a bit of blue thread on the floor, tied the feathers together with it and fastened them in his cap. Just the right place for them, he thought. When I put it on or take it off I'll think of Granny's words. They'll be good guidance for me. I'll always keep them in mind.

Then he put on his cap and coat again and went back to the gold-field. He didn't fasten his hut because there was naught in it. Only the empty sieve, and that wouldn't be worth picking up if it was lying by the roadside.

Ilya was a grown lad, he'd long been of an age to wed. He'd been working at the gold-fields six or seven years. It was serfdom in those times, and lads and maids had to go to work when they were still children. Many a one worked ten years for the Master before wedding. And as for Ilya, you could say he'd grown up at the gold-fields.

He knew all those parts up and down. The road to the gold-fields was a long one. At Gremikha, I've heard tell, they were getting gold nearly by White Stone. So Ilya thought to himself: I'll take a short cut through Zuzelka Bog. It's hot weather, it'll be dried up a bit, I'll be able to get across. I'll save three versts, maybe four.

So that's what he did. He cut straight through the woods, the way folks did in autumn. At first it was easy going, but then he got tired and found himself off the right way. You can't keep a straight path when you're jumping from tussock to tussock. You have to go where they are, and it may not be the way you want. He jumped and jumped, till he jumped himself into a sweat. At last he came to a glade with a hollow in the middle. There was grass growing there—feathergrass and such like, and pines grew up the sides. This was where the dry ground began. The only trouble was, Ilya didn't know which way to go next. With all the times he'd been round about there, he'd never seen that little gully before.

Ilya walked up the middle with the banks rising on both sides. He went on till he came to a little round pool like a spring, only he couldn't see the bottom. The water was clear, but a blue web covered the top; in the middle sat a spider, and that was blue too.

Ilya was glad to see water, he pushed the web away from one side to take a drink. But as he did so his head began to swim and he nearly fell in. He felt real sleepy.

Look how tired I've got on the bog, he thought. I'd better rest an hour or two.

He wanted to get to his feet but couldn't. Still, he did manage to crawl away a couple of yards to the slope. There he put his cap under his head and stretched himself out. He looked back—and there was a little old crone rising up out of the water. She wasn't more than twenty inches tall. Her dress was blue and so was the kerchief on her head, and she was sort of blue herself too, and so thin you'd have thought the first puff of wind would blow her away. But her eyes were young, and so big they didn't seem to belong to her face.

She fixed those eyes on the young fellow and stretched out her arms towards him. They kept growing longer, those arms, until the hands were close to his head. They seemed to have no substance, like wisps of blue mist, there was no strength in them that you could see, there were no claws, and yet they were fearsome. Ilya wished to crawl further away, but weakness overcame him.

I'll turn my head away, he thought, it won't be so awful.

He did so, and his nose came up against the feathers. And at once he had a fit of sneezing. He sneezed and sneezed, blood gushed from his nose, and still he could not stop. But he felt his head get lighter.

Then Ilya seized his cap and got on his feet. And there was the crone, standing in the same place, shaking with fury. Her hands stretched to Ilya's feet, but she could lift them no higher from the ground. Ilya saw the crone's scheme had failed, she had not the strength to clutch him. He sneezed a couple of times more and blew his nose.

"So you didn't manage it, eh! The nut's too hard for your teeth!"

He laughed, spat on the hands and turned to go. But the crone called after him, and her voice was as clear and loud as a maid's.

"Wait a bit, don't crow too soon! Ye'll not take your head away safe next time ye come!"

"I just won't come," Ilya answered.

"Aha! Ye're scared! Scared!" the old woman cried gleefully.

That stung Ilya, he stopped and said: "If that's the way, then I'll come just to spite you—and get some water from your spring."

Then the crone laughed and began to jeer at the lad.

"A braggart ye are, a braggart! Ye ought to thank your Granny Lukerya that ye've got away safe, and here ye are bragging! The man's not born that can drink from this spring!"

"We'll see about that, whether he's born or not," said Ilya.

But the crone kept on. "A windbag, that's all ye are! How'll ye get the water when ye're afeard to come close? Big words and naught else—unless ye bring others wi' ye. More stout-hearted than you are."

"You'll have to wait a long time for that," shouted Ilya, "for me to bring others to you! I've heard tell of ye before, about your ill deeds and how you beguile folks."

But the crone kept on with the same song.

"Ye won't come! Ye won't come! Too big a bite for you to chew! It's not for the likes o' you!"

Then Ilya cried: "All right, then. If there's a good wind Sunday, you can expect me."

"And what d'ye want a wind for?" asked the crone.

"Wait and see," said Ilya. "Wipe the spittle off your hands. And don't you forget."

"And what's it to you," said the crone, "what the hands are like that pull ye down to the bottom? I see ye're a bold lad, but all the same I'll get ye. Ye needn't put your faith in the wind, or your Granny's feathers either. They won't help ye!"

Well, so they parted with hard words and Ilya went his way, marking the path carefully. So that's what she's like, the Blue Crone, he thought. Looks as if she's just clinging to life, but got eyes like a maid's, they'd put a spell on you, and a voice that rings young too. I'd like to see her when she turns into a maid.

Ilya had heard a lot about that Blue Crone. There'd often been talk about her at the gold-fields. Folks might see her in empty bogs or in old mines. And wherever she sat, there would be wealth. If you could get her away, there'd be a whole pile of gold and precious stones. Scoop up as much as you could hold. Many sought her, but they either came back empty-handed or didn't come back at all.

It was evening when Ilya came to the gold-fields. The supervisor sent for him at once.

"Where've you been all this time?"

Ilya explained—he'd buried his Grandmother Lukerya. The supervisor was shamed a bit by that and sought something else to find fault with.

"What are those feathers on your cap? Adorned yourself for a feast?"

"They were left me by my grandmother," said Ilya. "I fastened them there to remember her by."

The supervisor and those who were by laughed at such an inheritance, but Ilya went on: "Aye, and mebbe I'd not change these feathers for all the Master's gold-fields. Because they're not plain feathers, they've got power in them. The white one's for the bright day, the black one's for peaceful nights and the red one's for the golden sunshine."

He spoke in jest, of course. But there was a fellow standing by—Kuzka Double-Snout. He was the same age as Ilya and their name-days were in the same month but that was the end of the likeness. That Double-Snout came from a well-to-do family. By rights he needn't have come to the gold-fields at all, he could have got easier work at home. But Kuzka had been hanging round the fields for a long time with thoughts of his own— mebbe I'll lay hands on something good, I'll be able to get it away all right. And sure it was, he'd guile and long practice in getting other folks' property into his own pocket. Take your eyes off something and before you knew, Double-Snout would have got hold of it, and you'd never see it again. In a word—a thief. He bore a mark for it, too. One miner had left his signature with a spade. It hit him slanting but left a scar for a reminder—his nose was slit to the lips. That's how he got the name Double-Snout.

Now, Kuzka had a bitter envy for Ilya. You see, Ilya was a strong lusty fellow, robust and gay, and his work seemed to get done of itself. When it was finished he'd eat, and then begin singing or maybe set a dance going. In an artel that can happen too. How could Double-Snout compare with a lad like that when he'd neither the strength nor the will, and he'd different things on his mind as well. But Kuzka accounted for it in his own way... Ilya must know some spell, that's why fortune was with him, and he could work without wearying.

When Ilya spoke of the feathers, Kuzka said to himself: That's it, that's where his magic power lies.

So of course that night he stole the feathers.

The next morning Ilya found them all gone. He thought he must have dropped them, and started searching about. Folks laughed at him.

"Where's your wits, lad! All these feet tramping about, and you think to find tiny feathers! They've been crushed long ago. And what's the good of them anyway?"

"What good, when they're my remembrance of Granny!"

"Remembrances you should keep in a safe place," they told him, "or else in your head, not carry them on your cap."

It's true what they say, Ilya thought, and he stopped searching for the feathers. It never even entered his thoughts that ill hands might have taken them.

Kuzka had his own care, to watch how Ilya managed now, without his grandmother's feathers. And he saw Ilya take his mining pan and go into the woods. Double-Snout made after him—he thought Ilya had found gold-bearing sand somewhere. But there was no sign of sand, and Ilya simply set about fixing a long pole to the pan. Over eight yards long, it must have been. That was no good for washing sand. But what could it be for? Kuzka watched closer than ever.

It was near autumn, with strong winds blowing. When Saturday came and the workers at the gold-fields went home, Ilya asked leave to go too. The supervisor made difficulties at first—"Not long since you went, and what d'ye want to go for, at that? You've no family and all the property you'd got, those feathers, you lost."... But in the end he let him off. And Kuzka would never miss a chance like that, he slipped off in good time to the spot where the pan on the long pole was hidden. He'd a good while to wait, but that's part of a thief's trade. You know the saying—a thief can out-wait a dog, let alone its master.

Early in the morning Ilya came, got out his pan and said aloud: "A pity the feathers are gone. But there's a good wind. It's whistling now, by midday it'll be blowing hard."

The wind was strong enough to make the trees groan with it. Ilya followed his marks, while Double-Snout slunk after him full of glee. "Here they are, the feathers! The ones that show the way to wealth!"

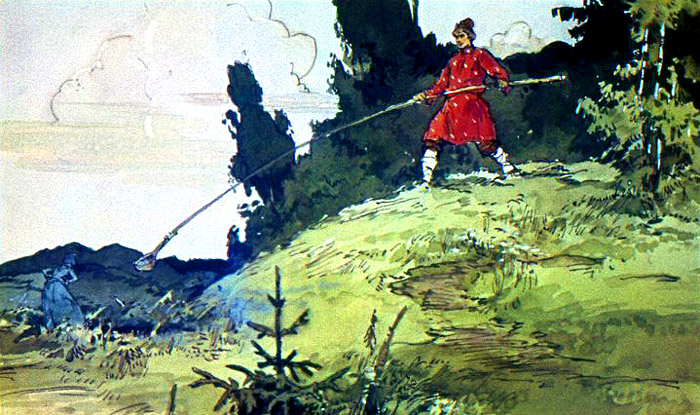

It took Ilya a long time to find his way back by the marks, and all the time the wind was getting less. When he came to the gully it had dropped entirely, not a twig was moving. Ilya looked at the spring and there was the crone standing by it, waiting.

"Ha, the cock-sparrow's back again!" she cried and her voice rang fresh and clear. "You've lost your Granny's feathers and guessed wrong with the wind too. What'll you do now? Run back and wait for a breeze? Mebbe it'll come to help ye!"

She stood a bit to the side, she didn't reach out for Ilya, but there was a mist over the spring like a blue fog, so thick it looked solid. Ilya took a run and thrust the pole with the pan on the end right into the middle of that blue fog; and not only that, he shouted: "Hi, look out, old crone, or I may happen to hit you!"

He scooped a panful from the spring but found the pan so heavy he could hardly get it out. The old woman laughed and her teeth shone white and young.

"Aye, let's see how you'll get your pan back again, whether you'll drink deep of my water!"

Mocked the lad, she did. Ilya felt it really was too heavy for him and lost his temper.

"Drink it yourself," he shouted.

He gathered all his strength, managed to lift the pan a little and tried to pour the water over the crone. She moved. He went after her. She got further off again. Then the pole broke and all the water was spilt. And the old woman laughed again.

"You'd do better to fasten your pan to a tree-trunk. More chance then!"

"You wait, you miserable crone," Ilya threatened. "I'll souse ye yet!"

Then the old woman said: "Well, enough. We've fooled a bit, now let be. I can see you're a daring lad and bold. Come here on a moonlight night, whenever ye will. I'll show ye wealth of all kinds. Take all you can carry. And if I'm not here on top, say only: 'I have brought no pan,' and you'll get all."

"And I'd like well to have you turn into a pretty maid too," said Ilya.

"About that we'll see," laughed the old woman and showed those young teeth again.

Double-Snout saw it all and heard every word.

"I'd better go back to the gold-fields," he thought, "and get some wallets ready. If only Ilya doesn't get it before me!"

So Double-Snout hastened back. But Ilya climbed the slope and made his way home. He crossed the swamp from tussock to tussock, got home and found a surprise—his grandmother's sieve was gone.

Ilya marvelled—who would want a thing like that? He went to see his friends, talked a bit with this one and that, and walked back to the gold-fields with the others, not across the swamp but by the road.

Five days passed and Ilya couldn't get it all out of his head. He thought of it at work and he dreamed of it at night. He'd keep seeing those blue eyes and hearing the ringing voice: "Come here on a moonlight night, whenever ye will."

At last Ilya made up his mind. I'll go. At least I'll see what wealth looks like. And maybe she'll show herself as a fair maid.

There had been a new moon not long before and the nights were getting lighter. And all of a sudden Double-Snout had vanished, everyone was talking about it. They sent to the village but he wasn't there. The supervisor had men search the woods—no sign of him there either. Though truth to tell, they didn't wear themselves out searching. Good riddance to bad rubbish, they thought. And that was the end of it.

Ilya went when the moon was full. He got to the place and found nobody. Still, he did not go down the slope, he only said quietly: "I've come without a pan."

As soon as he had spoken the words the old woman appeared and said kindly: "You're welcome, dear guest! I've waited long. Come and take all ye can carry."

She passed her hands over the spring as if she was opening a lid, and there it was, filled with treasures of every kind. Right up to the top. Ilya would have liked well to take a closer look, but he didn't go down the slope. The crone began to urge him.

"What are ye standing there for? Come and take all ye can put in your wallet."

"I've no wallet with me," he said, "and Granny Lukerya told me different. Only those riches are clean and secure that ye give a man yourself."

"So that's what you're like, no pleasing ye! Want it brought to ye! Well, be it as ye will!"

As the old woman spoke, a column of blue mist rose from the spring. And from this column came a maid, very fair to see, dressed like a tsarina, and half as tall as a good pine tree. In her hands she bore a golden tray heaped up with treasures of all kinds. There was gold dust, and precious stones, and gold nuggets nearly as big as a loaf. And that maid went up to Ilya and with a bow offered him the tray.

"Take it, fair lad!"

Now, Ilya had grown up at the gold-fields, he'd seen gold weighed and could guess the burden. So he looked at that tray and said to the old woman: "You're making a mock of me. There's no man on earth with the strength to lift that."

"Ye won't take it?" asked the old woman.

"No thought of it," Ilya answered.

"Be it as ye will. I'll offer ye another gift," she said.

In an instant the maid with the golden tray had vanished. Again a column of blue mist rose from the spring. And another maid came out. She was smaller. But she was fair too, and her dress was that of a merchant's daughter. In her hands she bore a tray of silver heaped with treasures. But Ilya would not take that tray either.

"It's beyond human strength to lift it," he said. "And besides, you're not giving it me with your own hands."

Then the old woman laughed, and her laugh was like a maid's.

"Very well, be it as ye will! I'll please you and myself too. But see ye don't regret it, after. Wait."

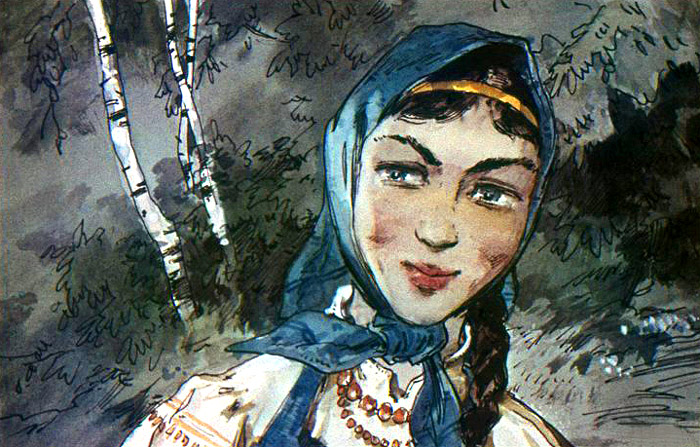

With her last word the maid with the silver tray was gone, and so was the old woman herself. Ilya waited and waited, but no one came. He was getting wearied of it, when he heard the grass rustling away to the side. He turned and saw a maid coming. An ordinary maid of ordinary human height. About eighteen, maybe. Her dress was blue and so was the kerchief on her head, and she had blue slippers on her feet. And fair she was, that maid—no words can tell. Eyes like stars, brows like bows, lips like raspberries and a thick russet braid thrown forward over her shoulder with a blue ribbon on the end of it.

She came up to him and said: "Take this gift, dear Ilya, it is given without guile."

With her own white hands she gave him Granny Lukerya's sieve filled full of berries. There were wild strawberries, and raspberries, and golden cloudberries and black-currants and bilberries. Every kind of berry. The sieve was full to the brim. And on top lay three feathers. One was white, one black and the third red, and they were tied together with blue thread.

Ilya took the sieve and stood there like one who'd lost his wits, he couldn't think where that maid could have come from and where she'd found all those berries in autumn. So he asked her: "Who are you, fair maid, 'and what's your name?"

Then she laughed and told him: "Men call me the Blue Crone, but to those who have quick wits and daring and a simple heart I show myself as you see me now. Only that comes but rarely."

Then Ilya knew who he was talking to, and asked: "Where did you get the feathers?"

"It was this way," she said. "Double-Snout came looking for wealth. But he fell into the spring and went down, and all his wallets with him. Only these feathers of yours came to the top. It's plain you've a simple heart."

Ilya did not know what more to talk of, and she stood there too and said naught, only played with the ribbon on her braid. At last she spoke.

"So, there it is, dear friend Ilya. I am the Blue Crone. Always old, always young. And placed here to guard the wealth for all time."

She was silent again for a moment, then she asked: "Well, have you looked your fill? Let it suffice, or you'll be seeing me in your dreams." With those words she sighed so it was like a knife in the lad's heart. He would have given all could she but have been a real maid. But she was gone.

For a long time Ilya stood there. The blue mist from the spring spread through the whole gully, and only then he turned to make his way home. It was light when he arrived. And just as he entered the hut, the sieve suddenly got heavy, the bottom tore out and nuggets and precious stones scattered all over the floor.

With wealth like that, Ilya bought his freedom from the Master at once, built himself a new house and bought a horse, but somehow he could not bring himself to wed. For he could not forget that maid. Peace of mind and sleep had left him. And Granny Lukerya's feathers were of no help either. Many a time he said: "Eh, Granny Lukerya, Granny Lukerya! You taught me how to get the Blue Crone's wealth, but how to rid myself of longing—of that you said naught. Likely you didn't know yourself."

So he pined and fretted, and at last he thought: Better go and throw myself in the spring than bear this torment.

He went to Zuzelka Bog, but still he took his grandmother's feathers with him. It was berrying time and folks were going out for wild strawberries.

Just as Ilya came to the woods he met a party of maids. Ten of them, maybe, with full baskets. One of the maids was walking a bit off to the side. About eighteen, she'd be. She'd a blue dress, and a blue kerchief on her head. And fair she was—no words can tell. Eyes like stars, brows like bows, lips like raspberries and a thick russet braid thrown forward over her shoulder with a blue ribbon on the end of it. The very picture of that other one. Only one thing was different—that maid had had blue slippers, while this one's feet were bare.

Ilya stood dumbstruck, staring. And she flashed him a look and another with those blue eyes, and laughed sort of teasing, showing her white teeth. Then Ilya came to himself a bit.

"How's it I've never seen you before?"

"Well, take a look now if it pleases ye," she said. "Ye can have it free, I'll not charge a kopek."

"Where d'ye live?" he asked.

"Go ahead and turn to the right," she said, "ye'll see a big tree-stump. Take a good run and smash your head against it till the sparks fly—then ye'll see me."

She was just teasing him with pert talk, the way maids do. But then she told him who she was and where she lived.

Aye, she told him honest and truthful, and all the time those blue eyes of hers enticed and drew him.

With this maid Ilya found his happiness. But not for long. She came from the marble quarries, you see, that's why he hadn't seen her before. Well, we know what that marble cutting meant. There were no maids fairer in our parts than the ones from there, but he who wed one was soon a widower. They worked with that stone from the time they were children, and they were consumptive one and all.

Ilya didn't live long either. He may have got the sickness from this maid or the other one. But however that may be, a big gold-field was found under Zuzelka Bog. You see, he didn't keep it secret, where he'd got his wealth. So folks started digging there, and came on rich gold.

I can mind the times they used to get a lot there. Only the spring none ever found. But there's a blue mist you can see there today, it always shows where there's gold.

It's little we've done yet, though. Just scraped the top a bit. We've got to go deeper. Far down, they say, is the Blue Crone's well. Real deep. Waiting for those who seek its riches.

Please support us

PayPal: anfiskinamama@gmail.com

Contact us if you have any questions or see any mistakes

© 2019-2026 Freebooksforkids.net