|

Free Online Illustrated Books for Kids |

Popular Andersen Fairy Tales Animal Stories Poetry for Kids Short Stories Categories list

P.Bazhov

The Flower of Stone

Translated by Eve Manning

freebooksforkids.net

Illustrated by V.Nazaruk

So it went on. Every day Prokopich gave Danilo some job, but it was all play. As soon as the snow came he sent the lad off with the neighbour to help bring wood. Well, what sort of work was that! Going, he just sat on the sledge and drove the horse, coming back he followed the load on foot. Stretched his legs a bit, ate his dinner and slept like a log. Prokopich got him a warm coat and cap, gloves and felt boots. The old man wasn't so badly off, you see. He was a serf, but he paid quit-rent and managed to earn a bit for himself. And soon he was real fond of Danilushko. The boy got to be like a son to him. So he didn't grudge him aught, and kept him out of the workshop for the time being.

Living so well, Danilushko began to pick up, and he got real fond of Prokopich too. Who wouldn't? He could see Prokopich was kind to him, and it was the first time in his life he'd ever been so well off. Winter passed, and Danilushko could run wild all he liked. One day he'd be on the pond, the next in the woods. And he'd keep looking and looking at Prokopich's work. As soon as he came home they'd be talking, Danilushko would tell Prokopich things and ask him—what's this, and why's that? So Prokopich would explain, and show him too. Danilushko took it all in. Sometimes he'd try for himself—"Here, let me do it." Then Prokopich would watch him work and help him when he needed it and show him how to do it all better.

In the end the bailiff noticed Danilushko by the pond. He asked one of his lickspittles: "What lad's that? He's always here. I've seen him plenty of times. Fishing on a weekday, a big lad like that! Ought to be at work. Someone's keeping him back."

Of course they soon found out, the bailiff's spies, and when they told him he couldn't believe it.

"Bring him to me," he said, "I'll look into this."

So Danilushko was brought to the bailiff.

"Whose lad are you?" he asked. And Danilushko said: "I'm an apprentice, I'm learning to carve malachite."

The bailiff took him by the ear. "So that's how ye do your learning, ye rascal!" And by the ear he led Danilushko to Prokopich.

The old man saw there was trouble brewing and thought how to shield the lad.

"I sent him myself to catch a perch. I felt a real hankering for fresh perch. I've a bad stomach, I can't eat other food. So I told the lad to catch me some."

The bailiff didn't believe the story. And he could see Danilushko looked quite different, he'd put on weight, he'd a good shirt and trousers and even top-boots. So the bailiff thought he'd find out how much Danilushko knew.

"Now then," he said, "show me what your master's taught ye."

Danilushko put on an apron, went to the bench and started telling this and showing that. And whatever the bailiff asked him, he knew it all. How to rough out the shape of the stone, and file it off, and polish it, the different mortars and when to use them, how to grind, how to inlay on copper and on wood—he had it all pat.

The bailiff tested him with one thing after another, and then he asked Prokopich: "Seems like you're suited wi' this one?"

"I don't complain," said Prokopich.

"You don't complain, but ye let him idle about. He's sent here to learn your craft, and spends his time fishing in the pond! Take heed! I'll give ye fresh perch, the kind ye'll mind to your dying day, and the lad'll get a taste of it too."

He stormed and threatened a bit, and then he went. But Prokopich turned to the lad in amaze.

"When did you learn it all, Danilushko? I've not taught ye anything at all yet."

"You showed me things and told me things," said Danilushko, "and I saw the way you do it."

Prokopich, he was so pleased the tears came to his eyes.

"Danilushko, son," he said, "whatever I know, I'll learn ye it all. I'll keep naught back."

But of course that was the end of Danilushko's easy, free life. The next day the bailiff sent him some work, and from then on he had his task to get done. Simple things at first, of course—brooches and boxes. Then it was candlesticks with decorations on them, till it came to the real fine work. Petals and leaves, flowers and patterns. It's a tedious craft, that with malachite. A thing may look naught, but the hours it takes to do! Well, Danilushko grew up on it.

When he made a snake bracelet from one piece of malachite, the bailiff said he was a real craftsman. He wrote of it to the Master. "We've a new craftsman in malachite carving, Danilo Nedokormysh. He works well, but he's young and he's slow. Shall I give him task-work or put him on quit-rent like Prokopich?"

Danilushko didn't really work slowly at all, it was amazing how quick and skilful he was. But Prokopich taught him to be clever. The bailiff would give Danilushko five days for some task, and Prokopich would say: "He can't do it. He needs a fortnight for work like that. The lad's only learning yet. If we hasten him he'll only spoil the stone."

Well, the bailiff would argue a bit, but he'd add on a few days. So Danilushko could take his time. He even learned to read and write a bit without the bailiff knowing. He didn't get much, of course, but still it was something. It was Prokopich put that idea in his head too. Sometimes the old man would do part of Danilushko's task himself, but the lad would never allow that if he saw it.

"Grandad—stop! For shame—am I to let ye sit at the bench and do my work for me? Why, your beard's green from malachite, your health's gone, and look at me!"

In those years, you see, Danilushko had grown into a real proper-looking lad. They still called him "Nedokormysh" out of old habit, but he was as big as this. Tall, rosy, curly-headed and gay—a lad to draw any girl's eye. Prokopich had even started talking about a wife for him, but Danilushko just shook his head.

"Time enough for that, they won't run away. First I'll be a real craftsman, then we'll think about it."

The bailiff got an answer back from the Master. "Have that apprentice of Prokopich's make a goblet for my house," he wrote. "Then we'll see whether to let him off on quit-rent or give him task-work. Only mind, see Prokopich doesn't help Danilo. If you let aught slip you'll answer for it."

The bailiff read that letter and sent for Danilushko.

"You'll work here, under my eye," he said. "You'll get a bench and tools, and stone'll be brought, all ye want."

When Prokopich heard it he was real cast down. What was this? What was the reason? He went to the bailiff, but of course the bailiff wasn't telling him anything, only shouted: "Mind your own business!"

So Danilushko had to go and work in a strange place. Before he left Prokopich warned him: "Mind, see ye don't work over quick, Danilushko! Don't let 'em see what ye can do."

At first Danilushko wais careful, he'd keep trying this and that and measuring here and there, but it was dull and tedious. Whether he did much or little, he had to sit there from morning to night. He got so tired of it, he couldn't stand it any more and started working the way he really could work. The goblet seemed to grow like a live thing and soon it was made. The bailiff took it as a matter of course and told Danilushko: "Make another like it."

Danilushko made a second and then a third. And when that was finished, the bailiff said: "That's the end o' your tricks. I've caught you and Prokopich both. The Master gave you this much time for one goblet, the way I told him when I wrote, and ye've made three. Now I know what ye can do. You don't fool me any more, and as for that old fox, I'll teach him to cover ye up. So it'll be a lesson to others!"

He wrote all that to the Master and sent the three goblets. But the Master —maybe he was getting weak in the head, or maybe he was angered with the bailiff for something, anyway, he did it all just the opposite. He put Danilushko on quit-rent, but so small it was naught to speak of, and forbade the bailiff to take the lad away from Prokopich; maybe if they worked together they'd be more like to think up something new. He sent a drawing with the letter, it was another goblet with all kinds of designs and adornments. There was a carved edge, and more carving round the middle, and leaves all over the foot. Real fancy, it was. And the Master wrote: "Let him take five years, but make it exactly like this."

So the bailiff had to eat his words. He told Danilushko what the Master had said, sent him back to Prokopich, and gave him the drawing.

Danilushko and Prokopich were real glad, of course, and the work seemed to go of itself. Danilushko soon started on the new goblet. It was difficult work, one wrong stroke would mean the whole thing spoilt, he'd have to start right from the beginning again. But Danilushko had a true eye, a sure hand and plenty of strength, so the job went well. Only one thing bothered him, there was plenty of difficulty but there was no beauty. He said as much to Prokopich, but the old man just scratched his head.

"What's that to you? They've drawn it that way, so it's how they want it. Plenty of things I've carved and polished, but what was the good of 'em, I couldn't tell ye."

Danilushko tried to talk to the bailiff, as though that were any use! The man stamped and brandished his fists. "Have ye gone clean daft? That drawing cost a mint o' money. It was mebbe done by the best artist in the city, and you think you know better!"

But then seemingly he called to mind what the Master had written, that the two of them might find something new, so he said: "Here's what you can do. Make that goblet from the design the Master sent, and then if you want to make another your own way, do as ye like about it. I won't stop ye. We've plenty of stone."

Well, Danilushko fell into deep thought. We all know, it's easy enough to see what's wrong with others' work, but try thinking up something yourself! Many a sleepless night it costs. Danilushko would sit working on the goblet he'd been given the drawing for, but his mind was far away, turning over flowers and leaves, picturing which would be best for patterns in malachite. He went about thinking all the time, real moping he got. Prokopich noticed it.

"Are ye sick, Danilushko lad? Go easy wi' that goblet. What's your hurry? Go out for a bit of a walk, ye do naught but sit over that work all day."

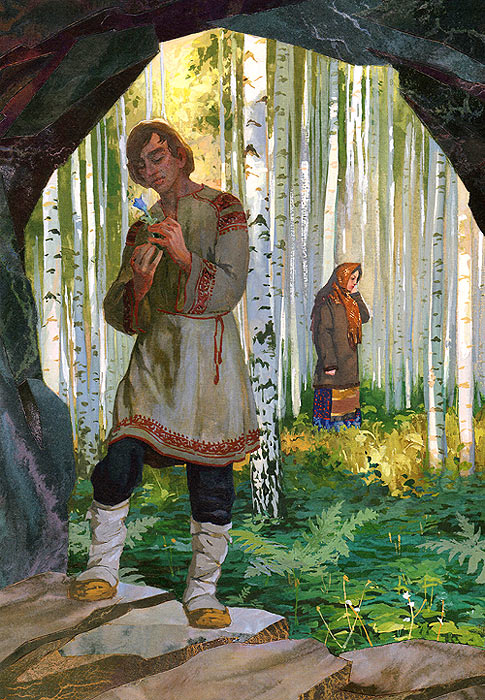

"Aye, I will," said Danilushko. "I might go into the woods a bit. Maybe I'll see what I want there."

After that he started going into the woods nearly every day. It was just at haymaking time, with wild flowers and berries everywhere. Danilushko would stop a bit in the meadows, or go to a glade and stand there looking all round. Then back he'd go to the meadow and stare at the grass and flowers, sort of searching. There were a lot of folks about at that time, and they'd ask him if he'd lost something. He'd smile sort of sadly and say: "It's not what I've lost, it's what I can't find."

They begain to say the lad wasn't all there.

Then he'd come home and go straight to the bench, and sit at it till morning; and when the sun rose he'd go back to the woods and meadows. He started bringing home flowers and leaves, mostly poisonous ones, wild garlic and hemlock, thornapple and marsh tea and all sorts of other marsh plants. His face got thin and his eyes were sort of wild, and his hand lost its sure cunning. Prokopich got real concerned, but Danilushko told him: "That goblet gives me no peace. I want to bring forth all the power of beauty in the stone."

Prokopich tried to talk him out of it.

"Why fret yourself over that? You're fed and warm, what more d'ye need? Let the gentry play wi' their whims and fancies. So long as they let us alone. If they get some idea of a design, we'll make it, but why should we rack our brains for them? Picking up an extra load, that's all it is."

But Danilushko stuck to it.

"It's not for the Master I'm racking my brains," he said. "I just can't get it out of my head. I can see the stone we've got here, look at it, and what do we do wi' it? Grind it and carve it and polish it, and all the wrong way. And now I'm taken wi' the wish to work it so I can see its full power of beauty, and let others see it, too."

Times Danilushko would sit down again with that goblet the Master ordered. He'd work on it and laugh at it all the time.

"A stone ribbon the moths ha' been at, and a border the rats ha' nibbled."

Then all of a sudden he pushed that work to one side and started on something else. He stood there by the bench without even stopping to rest. "I'll make my own goblet with a pattern of thornaipple," he said to Prokopich.

The old man tried to stop him. Danilushko didn't want to hear a word at first, but after three days or maybe four, when he got a bit stuck, he gave way.

"All right, then," he told Prokopich, "I'll finish the Master's goblet first, and work on my own after. Only don't you try to put me off then.... For I can't get it out of my head."

"Well and good," said Prokopich, "I won't bother ye." But to himself he said: The lad'll get tired of it, he'll forget. He needs a wife, that's what's wrong with him. Nothing like a family to drive the vapours out of his head.

So Danilushko set to work on the goblet. There was plenty in it to keep him busy, enough for a year and more. He worked hard and never spoke of the thornapple; Prokopich began talking of a wife.

"There's Katya Letemina, what's wrong with her? A real good maid, she is. Not a thing ye can say against her."

Now, there was a bit of cunning in Prokopich's talk. He'd seen Danilushko looking Katya's way a long time, and she didn't seem averse. So Prokopich led the talk to her, as though by accident. But Danilushko was as stubborn as a mule.

"That can wait," he said. "First I'll get the goblet done. I'm sick of it. I'd as soon smash the hammer down on it, and you start telling me to wed. I've talked to Katya, she'll wait for me."

Well, Danilushko finished that goblet, the one made like the Master's drawing. He didn't tell the bailiff, of course, but he thought to have a bit of a merrymaking at home. Katya, his sweetheart, came with her parents, and a few more, mostly malachite carvers. Katya was amazed at the goblet.

"How could ye carve a pattern like that," she said, "and never break the stone! And all so smooth and polished!"

The craftsmen too had their word of praise.

"Line for line with the drawing. Not a fault anywhere. And clean work. Couldn't be done better, and ye did it quickly too. If ye go on this way, we'll have a job to keep up wi' ye."

Danilushko listened and listened, and then he burst out: "That's just what's wrong, naught to find fault with. Clean and smooth, the pattern plain, all just like the drawing, but where's the beauty in it? Here's a flower, just a common weed, but when ye look at it, it brings joy to your heart. But the goblet—who'll rejoice to look at that? What good is it? Folks'll look at it and they'll marvel like Katya here, they'll say—what an eye, what a hand that man had that made it, and where did he get the patience to do all that finicking work and never break the stone?"

"And if he did chip it," laughed the craftsmen, "he stuck the bit back and polished it so ye'll never find the place."

"Aye, that's it.... But where's the beauty of the stone itself—tell me that? A vein runs down here, and you bore a hole in it and cut a flower. What's the good of it there? Just spoiling the stone. And look what stone it is! The very best—the best, d'ye understand me?"

He got all hot about it. He'd drunk a glass or two, you see.

The craftsmen started telling Danilushko the same thing Prokopich always said.

"Stone's stone. What'll you do with it? Our job's to grind and cut, that's all."

But there was an old man sitting there. He'd taught Prokopich and the others too. They all called him Grandad. He was ancient and shaky, but he understood what the talk was about, and he said to Danilushko: "Ye'd best keep off them kind o' thoughts, son. Put 'em from your head. Or mebbe the Mistress'll take ye for a mountain craftsman."

"What are those, Grandad?"

"They're skilful craftsmen who live in the mountain, and no man ever sees them. Whatever the Mistress wants, they make it for her. I saw a bit of their work once. Eh, that was real work, that was! You'll never see the like here."

They all pricked up their ears at that, and wanted to know what he'd seen.

"It was a serpent," he said, "like ye make for bracelets."

"Aye, well, what was it like?"

"Naught like the ones here, I tell ye. Any craftsman who saw it would know at once it wasn't our work. Our serpents, no matter how good they are, they're but stone, but this was like as if it was living. A black line down the back, and eyes—ye'd think it was just going to up and sting ye. They can make anything! They've seen the Flower o' Stone, they've got the understanding of beauty."

Now, when Danilushko heard that flower spoken of again, he started asking the old man what it was and all about it. And Grandad answered him honestly.

"I couldn't tell ye, my son. I've heard tell of such a flower. But it's not for our eyes. If a man sees it life loses all its sweetness for him."

Danilushko only said: "I'd like to look at it."

Then Katya, his sweetheart, she got all upset.

"What are you saying, Danilushko! Have you got tired already of life's sweetness?" And she burst into tears. Prokopich and the others tried to smooth it over, and laughed at the old man.

"You must be getting weak in the head, Grandad. It's all nonsense. Why d'ye muddle the lad's head with your fancies?"

Then the old man got angry and struck the table with his fist.

"That flower exists! It's truth what the lad says—we don't understand the stone. And that flower holds the heart of all beauty."

The other men laughed at him.

"Ye've taken a drop too much, Grandad!"

But the old man stuck to it. "There is a Flower of Stone!"

Please support us

PayPal: anfiskinamama@gmail.com

Contact us if you have any questions or see any mistakes

© 2019-2026 Freebooksforkids.net