|

Free Online Illustrated Books for Kids |

Popular Andersen Fairy Tales Animal Stories Poetry for Kids Short Stories Categories list

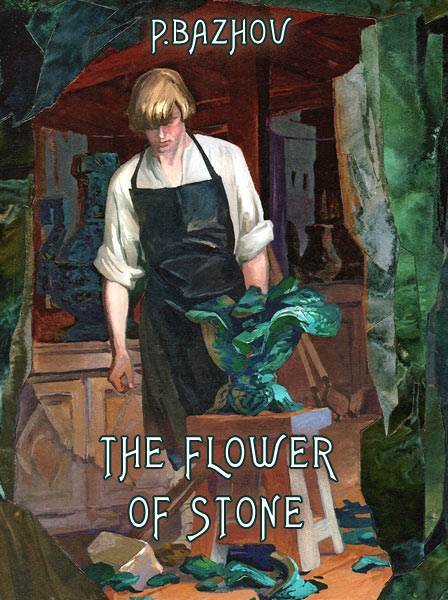

P.Bazhov

The Flower of Stone

Translated by Eve Manning

freebooksforkids.net

Illustrated by V.Nazaruk

It wasn't only Mramor that was famous for stone carving, folks say there were craftsmen in our villages too. Only ours mostly worked with malachite, because there was plenty of it, and the very finest kind. The things they made, you'd just stare and wonder how they did it.

There was a master craftsman in those days called Prokopich. He was the best there was in carving, none other could come near him. But he was getting old, so the Master told the bailiff to give Prokopich an apprentice.

"Let some lad learn his craft, all of it, to the last secret."

But Prokopich—maybe he just didn't want to give away the secrets of his craft, or maybe it was something else, but he didn't teach any of them much. All they got from him was bumps and bangs. He'd buffet a lad till his whole head was bruised and pull his ears nearly off, and then tell the bailiff: "He's no good. His eye's not straight and his hand's like a foot. He'll never learn."

The bailiff must have been told to humour Prokopich.

"If he's no good, he's no good... We'll find ye another." So the next lad would be sent.

The boys all heard about Prokopich's teaching. They'd roar and howl at the very thought of going to him. And fathers and mothers too, they were loth to send their boys to be knocked about, and tried to keep them out of the way if they could. Besides, it wasn't a healthy trade, carving malachite. The dust was real poison. Folks kept away from it.

But the bailiff had his orders from the Master so he went on sending lads to Prokopich to learn his craft. And Prokopich would torment them a while as his way was, and then send them back. "No good."

At last the bailiff lost his patience. "How long will ye keep this up? No good, no good—when'll ye say 'good'? Make something of this one."

But Prokopich was stubborn. "All the same to me... I can teach him ten years if ye like, but naught'll come of it."

"What lad do ye want, then?"

"You needn't send any, for me. I'm not pining for 'em."

So it went on. The bailiff and Prokopich tried plenty of lads, but it always ended the same—with bruises on their heads and only one idea inside, to get away. Some spoiled things on purpose so Prokopich would turn them off.

Then it came to Danilo Nedokormysh's [famished] turn. An orphan, he was. Twelve, maybe, or a bit more. A tall, spindly lad with long legs, thin as a rail— you'd wonder how he kept body and soul together. But he'd a comely face, with blue eyes and curly hair. First he was made a page at the Big House, to pick up handkerchiefs and snuff-boxes and the like, and run errands. But he didn't seem made for it. Other lads are quick and smart, as soon as you look at them they're standing up straight—yessir, yes ma'am, what can I do? But that Danilo, he'd be off in some corner staring at a picture or decoration, just standing there staring. They'd call him and he wouldn't even hear. He was flogged at first, of course, then they gave him up as a bad job.

"Head in the clouds. Moves like a snail. Never make a good lackey of him."

He wasn't sent to the mines, though. He'd never have lasted a week on that work. So he was put to help the herdsman. But he was no good at that either. He seemed to be trying his best, but everything went wrong with him. Half the time he was in a sort of daze. He'd stand staring at some bit of grass while the cows wandered off. The herdsman was a kindly old fellow and sorry for the orphan, but all the same he had to rate him.

"What's going to come o' ye, Danilo? Ye'll ruin all for yourself, and my old back'll get the whip too. What good are ye? What are ye thinking about?"

"I don't know myself, Grandad... Just—naught special. I was watching, like... There was a bug crawling on a leaf. It was not quite blue and not quite grey, and there was just a mite of yellow under the wings; and the leaf was a long wide one... The edge was jagged, curling a bit, like a fringe, and darker, but in the middle it was real bright green, as if it had just been painted. And there was the bug crawling about on it."

"Well now, aren't ye a fool, Danilo! Are ye here to watch bugs on leaves? Let it crawl where it wants, ye're here to herd cows. Get all that nonsense out o' your head before I tell the bailiff!"

There was one thing Danilo could do, though. He learned to play the horn better than the old man himself. Real tunes, it was. When the cows came home in the evenings, the women and maids would ask him: "Play us a song, Danilushko."

He'd start playing, but it wasn't like any song they'd ever heard. It would be like the forest rustling and the brook babbling and birds singing all at once, real nice it sounded. Because of those tunes all the women started making much of Danilushko, some would mend his clothes, others would cut him new foot-rags of homespun, or make him a new shirt. And food, they all vied in treating him to the best and finest. The old herdsman, he was real pleased with Danilo's tunes too. But not always. For once Danilo began playing it was just as if he'd no cows to mind at all. And that was what brought misfortune on them.

Danilushko got lost in his tunes one day when the old man had dozed off a bit, and some of the cows strayed away. When it was time to get them together and drive them to the common, there was this one gone and that one gone. They sought and sought, but what chance was there to find them? It was right by Yelnichnaya, that's close to the woods, they're thick and dark, with plenty of wolves about. They found one cow and that was all. So they took the herd home, and told about the missing cows. Of course, men went out on horseback and on foot to search, but they never found a single one of them.

You know the way it was in those days. For every fault, bare your back. And to make it worse, one of the lost cows belonged to the bailiff. No hope of getting off lightly this time. First they had the old man to the whipping post. Then came Danilo's turn, and he was so thin and spindly, the flogger looked at him and said: "That one'll faint wi' the first stroke—if it doesn't let his soul out at once."

All the same he gave his whip a good swing, but Danilushko didn't make a sound. A second blow, and a third—and not a cry from the lad. Then the flogger got savage and started laying on as hard as he could.

"I'll make you yell, you stubborn cur! Yell you shall! You shall!"

Danilushko was shaking all over, tears rolled down his face but not a sound did he make. Bit his lips and kept it in. He was flogged till he fainted, but never a cry out of him. The bailiff—he was there, of course—was real amazed.

"There's one that can stand knocking about! I know now where I'll send him, if he's still alive."

Well, he did get better, Granny Vikhorikha put him on his feet again. That's an old woman they tell of. She Was famous round about for her simples. She knew the powers of herbs, what to use for toothache, or sprains, or the rheumatics—all of it. She'd go out and seek the herbs herself, each one at the time when it had its full strength. And then she'd brew her leaves and roots, or make salves of them.

It was Heaven for Danilushko, living with that old woman. She was kind, you see, and liked to chat; and all her hut was hung with her dried grasses and flowers and roots. Danilushko would look at this one and that and ask her—what's it called? Where does it grow? What's the flower like? And the old woman told him about them.

One day Danilushko asked her: "D'ye know all the flowers round our way, Granny?"

"Well, I won't boast," she said, "but I can say I know those that flower for men to see."

"But are there any that flower in secret?"

"Aye, that there are," said old Vikhorikha. "Ye know the fern? They say it flowers on St. John's Day. It's a magic flower, that is. It'll show where there's hidden treasure. But it's evil for a man. Then there's a flower that breaks rock—it's like a will-o'-the-wisp. Catch it and it'll open all locks for ye. It's a robber's flower. And then there's the Flower of Stone. It grows in the malachite mountain, folks say. It has great power on the Snake Festival. But unhappy the man that sees it."

"Why's he unhappy, Granny?"

"That, my child, I can't tell ye because I don't know myself. It's the way it was told me."

Maybe Danilushko would have gone on living with Vikhorikha, but the bailiff's lickspittles saw the lad was getting on his feet and hurried off to tell of it. So the bailiff sent for Danilushko.

"Off you go to Prokopich," he said, "learn to carve malachite. Just the job for you."

Naught to be done, so Danilushko went, though it seemed like a puff of wind would blow him over.

Prokopich took one look at him. "Picked a fine 'un this time. There's strong, lusty lads can't learn my craft, what'll I do with a lad who can hardly stand on his feet?"

So Prokopich went to the bailiff. "He's no good. Might kill him by accident, like—and then have to answer for it."

But the bailiff—not a word would he listen to.

"He's given ye to teach—teach him and less talk about it. He's tough, that lad is, for all his sickly looks."

"Well, be it as ye will," said Prokopich. "I've said my say. I'll teach him, but I hope I won't be blamed."

"None to blame ye, the lad's alone in the world, do as ye like with him."

So Prokopich went back home again, and there was Danilushko at the work-bench, staring at a slab of malachite. There was a mark on the slab where the border was to be carved. Danilushko was looking at it, shaking his head. Prokopich wondered what the new lad could be about. So he asked in his usual gruff way: "What's that ye're doing? Who told ye to meddle wi' the work? What are ye staring at?"

"Seems to me, Grandad," said Danilushko, "ye oughtn't to carve the border that side. Look, here's how the pattern goes, ye'll cut right through it."

Well, of course, Prokopich started to shout at him.

"What's that? Who d'ye think you are? A master craftsman? Seen naught, know naught and start airing your ideas! What do you understand about it?"

"I know this is spoiled, that I do know," said Danilushko.

"Who's spoiled it? Eh? You say that to me—you, ye snot-nose, to me, the best craftsman? I'll give ye spoiled—ye'll be under the sod!"

He went on shouting and bawling, but he didn't even touch Danilushko. You see, he'd puzzled a good bit over that slab himself, over which side he'd carve the border. And Danilushko had hit the nail right on the head. So Prokopich shouted till he got tired and then he said kindly enough: "Well, Master Craftsman, show me how you think it ought to be done."

Danilushko started pointing out this and that.

"Look, the pattern could go this way. Or better, make the slab narrower, carve the border where there's no pattern and just leave the natural pattern on top."

Prokopich growled: "H'm—aye. . .. Ye're full o' knowledge. Mind ye don't spill it." But to himself he thought: the lad's right. Something ought to come of this one. But how can I teach him? One thump and he'll turn up his toes.

He thought this way and that, and then he asked Danilushko: "Whose son are ye, Clever?"

Danilushko told him all about himself. An orphan, couldn't remember his mother and as for his father, didn't even know who he was. Always been called Danilo Nedokormysh, but what his real surname was he'd never heard. He told Prokopich how he'd been at the Big House and why he'd been sent away, how he'd spent the summer herding and how he'd been flogged. The old man felt quite sorry for him.

"I can see ye've not had a good time of it, lad, and now on top of it all ye've been sent here to me. Our craft's no easy one." Then he made a show of anger again and growled. "That's enough, now, that'll do! Chatterbox, that's what ye are. If tongues were hands they'd all be grand workers. Chit and chat day and night! An apprentice—huh! We'll see tomorrow what you're made of. Get your supper, it's time to sleep."

Prokopich lived alone. His wife had died long before, and one of the Neighbours, old Mitrofanovna, came in to look after things. In the morning she'd cook something and clean up, and in the evening Prokopich managed all he wanted for himself.

They had supper, then Prokopich said: "Lie down here on the bench."

Danilushko took off his shoes, put his knapsack under his head, covered himself with his homespun coat, shivered a bit—it was chilly in the hut in autumn—but soon fell asleep. Prokopich lay down too, but he couldn't get to sleep, all the talk about the malachite pattern kept going round and round in his head. He tossed and grunted a bit, then he got up, lighted the candle, went to the bench and started measuring the slab this way and that. Tried one band of carving, then another, made the border wider, made it narrower, then he turned it all round the other way. But no matter what he tried, it always came out that the lad's way was the best.

"So that's the sort he is, this Nedokormysh!" Prokopich marvelled.

"Green as grass, and teaches an old craftsman. What an eye! Oh, what an eye!"

He went softly into the lumber room, got a pillow and a big sheepskin coat, put the pillow under Danilushko's head and covered him with the skin. "Sleep well, Sharp Eyes," he said.

The lad didn't waken, he just turned over on the other side and stretched out under the sheepskin—nice and warm he felt—and breathed sort of heavy, like a cat purring. Now, Prokopich had never had any children of his own, and Danilushko just caught at his heart. He stood looking down at the lad, while Danilushko slept on, breathing heavily with just a bit of a whistle in it. And Prokopich kept wondering how he could make the lad stronger and sturdier, so he wouldn't look as if a puff of wind would knock him off his feet.

"A sickly boy like that to learn my trade! The dust—it's poison, it'll get on his chest before we know it. He ought to rest and put some flesh on him first, then I'll teach him the work. There's a craftsman in him."

The next morning he told Danilushko: "You start off by doing odd jobs round the house. That's the way I have it. Understand? First, go and gather hips, the frost's just touched them, they ought to be right for buns. But see ye don't wander off too far. Just get as many as ye find. Take a crust o' bread with ye—something to bite on in the woods. And go to Mitrofanovna, tell her to fry a couple of eggs and give ye a pitcher of milk. Understand all that?"

The next day he told the lad: "Go and catch me a goldfinch wi' a good loud voice, and a linnet, a lively one. See ye're back by nightfall. Understand?"

Danilushko caught both and brought them home.

"Aye, they're good ones," said the old man, "Go catch some more."

Author: Bazhov P.; illustrated by Nazaruk V.Please support us

PayPal: anfiskinamama@gmail.com

Contact us if you have any questions or see any mistakes

© 2019-2026 Freebooksforkids.net