|

Free Online Illustrated Books for Kids |

Popular Andersen Fairy Tales Animal Stories Poetry for Kids Short Stories Categories list

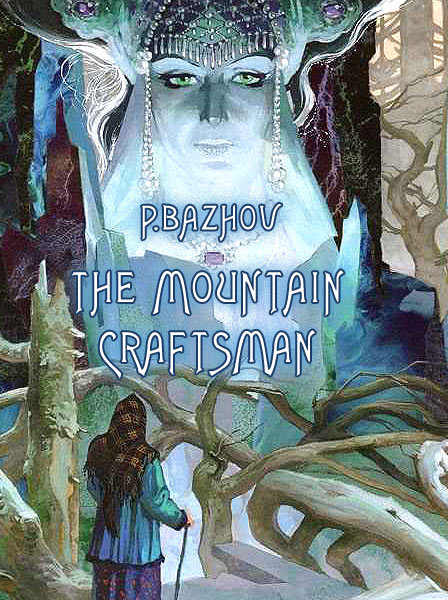

P.Bazhov

The Mountain Craftsman

Translated by Eve Manning

freebooksforkids.net

Illustrated by V.Nazaruk

After Danilo disappeared his betrothed maid, Katya, remained unwed. Two years passed, or maybe three, and she was getting past the age. In our parts, they're reckoned old maids after twenty or so. The young fellows seldom send matchmakers to such, it's mainly widowers think of them. But Katya, she must have been real comely, for the lads still kept after her. But none would she take. "I'm promised to Danilo," she said. Folks tried to talk sense into her.

"Think what you're about! Promised ye were, but naught came of it. No use thinking of that now. He's dead and gone."

But Katya would hear none of it.

"I'm promised to Danilo. Maybe he'll come back yet."

"He's long dead. Must be."

But there was no moving her.

"There's none has seen him dead, and for me he lives."

They thought the maid was crazed and let her alone. Some even made a mock of her, called her Dead Man's Bride. The nickname stuck, and soon she was called Katya Mertvyakova [From mertvets, a corpse], just as though she'd never been called by any other name.

About that time there came a sickness, and Katya's father and mother both died. She'd got plenty of relations, three brothers and sisters as well, all married. But they only started quarrelling at once, who was to step into their father's shoes. Katya saw naught good would come of all this.

"I'll go and live with Prokopich," she said, "he's old and feeble, I can look after him a bit."

Of course her brothers and sisters were against it.

"It's not fitting. Prokopich is old, that's true, but all the same folks may talk."

"What's that to me?" she answered. "It's not my tongue that'll be filthy. And Prokopich isn't a stranger, he's my Danilo's foster-father. And 'father' is what I'll call him."

So she went. To be sure, her family didn't try very hard to stop her. One less, so much bother the less, they thought. And as for Prokopich, he was glad enough to have her.

"Thank ye, Katenka, for thinking of me," he said.

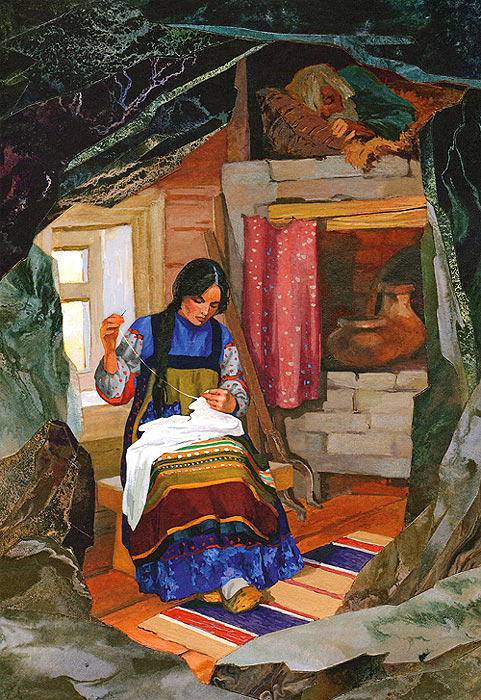

So they started housekeeping together. Prokopich would work at his bench, while Katya was busy in the garden, or cooking, baking and so on. There wasn't so much to do for just the two of them, and Katya was brisk and capable, she was soon through with it all; then she'd sit down with her sewing or knitting. At first it was all as comfortable as you could wish, but after a bit Prokopich began to ail. He'd work one day and stop in bed two. It was old age, he was just worn out, that was all. And Katya started wondering how they were going to keep on. "Women's crafts won't feed us, and I know no other."

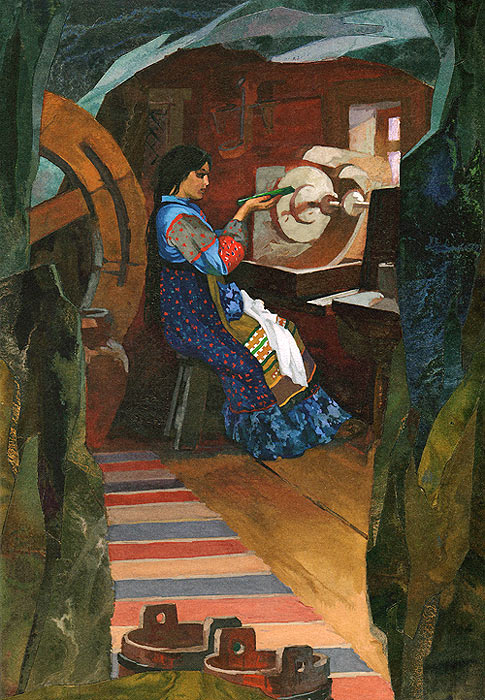

One day she said to Prokopich: "Teach me something of your craft, Father, some of the easier things."

Prokopich only laughed.

"What are ye thinking of! That's not maids' work, malachite. I've never heard tell of such a thing in all my days."

Still she began watching Prokopich when he was at work. She'd help him a bit, too, as much as she could. Filing a bit here, polishing there. Prokopich would show her this or that. Not real fine work, of course. Medallions for brooches, handles for knives and forks and such like, whatever came along. Cheap stuff. It only brought in a few small coins, but it helped.

Prokopich didn't live much longer. Then Katya's brothers and sisters got after her again.

"Now you'll have to wed, will ye, nill ye. You can't live here all alone."

But Katya cut them short.

"That's naught for you to fret over. I want none of your suiters. Danilushko'll be back some day. He'll learn all he wants to know, there in the mountain, and then he'll come."

The brothers and sisters lifted their hands, aghast.

"Are ye in your right mind, Katya? It's a sin even to say such things. Waiting for a man that's dead long ago! Ye'll be seeing spooks next."

"Have no fear o' that," she said.

"But how d'ye think you're going to live?" they asked.

"Ye needn't fret about that either," she said. "I'll manage alone."

Well, then they thought Prokopich must have left some money, and started again with their old song.

"A fool ye are, naught else! If ye've got money, ye surely need a man in the house. Or one fine day someone may come after it. Wring your neck like a chicken's. And that'll be the end o' ye."

"Soon or late, my end'll come when it's fated."

Brothers and sisters kept on a long time, some shouting, some urging, some weeping. But Katya knew her mind.

"I'll manage alone. I don't need any o' your suiters. I've a lad o' my own."

In the end, of course, they got angry.

"Keep away from us, then!"

"Thank ye," she said, "dear brothers and kind sisters. I'll remember. And you too, don't forget; when ye pass—pass by."

Laughed at them, she did. So they banged the door behind them.

Katya was left all alone. She cried a bit at first, of course, but then she said: "No! I won't give in!"

She wiped her eyes and started on her housework. She washed and scoured—a real good clean-up. As soon as she'd finished, she went to the work-bench. There too she ordered and arranged everything to her mind. What she didn't need, she put out of the way, and what she'd be wanting all the time was right under her hand. When she'd everything to her liking, she sat down to work.

"I'll try if I can make one medallion alone."

She looked round for stone, but there wasn't any that would do. She still had the pieces of Danilo's thornapple goblet, she treasured them and kept them wrapped in a separate bundle. Prokopich had had plenty of stone, of course, but right up to his death he'd always been doing big jobs. So the stone was in large pieces. The smaller ones had all been used for decorations.

"Well," said Katya to herself, "seems like I'll have to go to the dumps by the mines, mebbe I'll find something I can use."

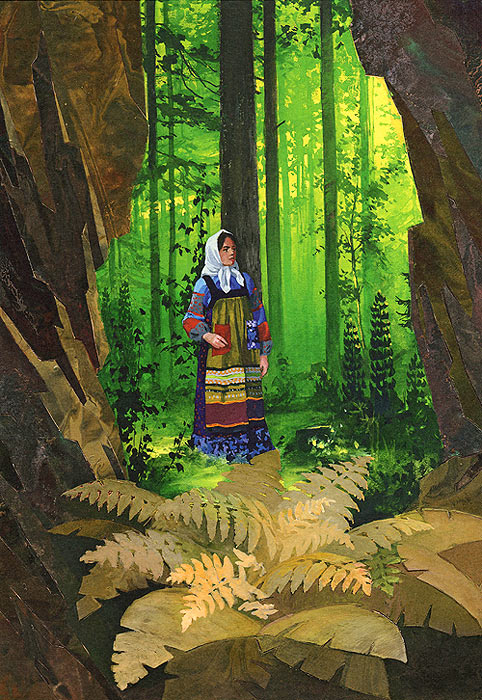

She'd heard Danilo and Prokopich talk about going to Serpent Hill for stone. So that was where she went.

There were always plenty of folks on Gumeshky picking over the rock and ore, or carrying it away. They all turned to look at Katya when she came by with her basket. She didn't like the way they stared so she went past the dumps and round to the other side of the hill. Woods were still standing there, and Katya went through them right to Serpent Hill and sat down on a rock. Her heart ached as she remembered Danilushko and tears ran down her face. She was all alone, only the trees round, she could let them run. And so they dropped and dropped on the ground.

After she'd wept a bit she looked down—and there was a piece of malachite right by her feet, half buried. How was she to get it out without a pick or crowbar? But she found she could move it a bit with her hand. It wasn't stuck very firmly. She found a stick and began digging the earth away from round it. She scraped away as much as she could, then tried to move it again. It came up quite easily, with a crack—like breaking off a dry twig. It was a flat slab, not very large—three fingers in thickness, as wide as your palm, and two hands long. Katya wondered at it.

"Just as if it was put there for me. See how many brooches I'll make by just cutting it. And hardly anything lost."

She took the stone home and set to work filing it into pieces. It wasn't quick work, and Katya had plenty to do round the house as well, so she was busy all day and had no time to grieve. But when she sat down at the work-bench, she'd start thinking of Danilushko.

If only he could see the new craftsman that's here! Sitting in his and Prokopich's place!

Of course there were scoffers, and worse. You'll always find those.

One night, just before a holiday it was, when Katya sat up late working, three young fellows climbed her fence. Maybe they just wanted to frighten her, or maybe something more, who knows. But they were all a bit drunk. Katya was filing away and didn't hear them come into the entry. The first thing she knew was when they started hammering at the inner door.

"Hey, open up, Dead Man's Bride! Here's some live 'uns come to see ye!"

First Katya tried fair words. "Go away, let me alone, lads!"

She might have spared her breath. They kept battering at the door, any minute they'd break it down. So then Katya took off the hook and threw the door wide open.

"Come in if ye dare. Who's the first to get this?"

They looked—and there she stood with an axe.

"Here, none o' your fooling," they said.

"Think I'm fooling?" she answered. "The first that sets foot inside gets this in his head."

Though they were drunk, they could see there wasn't any fooling about that. The maid was tall, with straight shoulders, and a grim look in her eye. And she handled the axe as though she knew how to use it. So not one of them dared go in. They shouted a bit, then they made off, aye, and went and talked about it too. Of course the other lads laughed at them, three of them running away from one maid. They didn't like that, so they made up a tale: Katya hadn't been alone, she'd had the dead man standing behind her.

"And so awful he looked, your feet 'ud run of themselves."

Maybe the other lads believed it, or maybe not, but anyway, talk started going round.

"Unhallowed things are in that house. There's cause why she lives alone."

The talk got round to Katya, but little she cared. Let them gossip, she thought, all the better if they're a bit scared. They won't be trying to get in.

The neighbours wondered to see her sitting at the bench, and made a mock of her.

"Trying to do men's work! We'll see how far she gets!"

That was worse. Katya had been wondering herself—will I be able to do it alone?.. But then she plucked up courage again. Market wares—what craft does that take? Just so long as they're polished smooth... That much I can surely do!

When Katya sawed through the stone, she could see at once it had a pattern like you seldom find, and it was clear at a glance where she ought to cut it across. Katya was amazed to see how well the work went. She cut the stone at the places it showed and then started to grind it. That's not such a difficult job, but it needs practice all the same. At first it went slowly, and then she got the knack. The brooches came out real well, and hardly a bit of waste, only what was taken off in grinding.

Katya finished her brooches, wondered again at the stone being just as if it was made for her, and then started thinking where to sell them. Prokopich used to take things like that into the town and sell them to a shop. Katya had heard tell of it many a time. So she decided to go there.

I'll ask if they'll take other work I do, too, she thought.

She fastened up the hut and set off on foot. Nobody in Polevaya noticed she'd gone to town. She found out where the merchant who'd bought Prokopich's things had his shop and went straight to him. When she looked round she saw the shop was full of stoneware, and there was a whole cupboard with a glass front that had only malachite brooches. There were a lot of people, some buying, others offering their work. And the merchant stood there, stern and very dignified.

At first Katya was afeard to speak to him. But then she took heart.

"Have ye any need of malachite brooches?"

The merchant pointed at the cupboard.

"Can't you see how many I've got already?"

The craftsmen selling their wares caught up the song. "Plenty o' folks trying their hand at that stuff. Just spoiling stone. Can't even see that for brooches ye need a good pattern."

One of the craftsmen was from Polevaya, he pulled the merchant aside and said in his ear: "She's a bit lacking, that maid. The neighbours have seen her at the work-bench. A fine botch she'll ha' made."

Then the merchant turned to her and said: "Well, show me what you've got."

Katya handed him a brooch. He took one look at it, and stared at her.

"Where did you steal this?"

That made Katya angry, of course, and she spoke up boldly.

"What right have ye to say that to a woman ye don't even know? Just look here, if ye're not blind, where could I steal all those brooches, all o' the same pattern? Tell me that!" And she poured them out on the counter.

The merchant and the craftsmen saw—yes, it was all the same pattern. And a kind you don't often see. There was a tree growing in the middle, and a bird sitting on a twig, and another bird down below. It was clear as clear, and clean work. The buyers heard the talk and came crowding round to look, but the merchant covered up the brooches. Found an excuse for it.

"Can't see them properly all in a heap. I'll put them under the glass. Then ye can choose what ye want." To Katya he said: "Go in there, through that door. You'll get your money in a minute."

Katya went, and the merchant followed her. He fastened the door and asked her: "What d'ye want for them?"

Katya knew what Prokopich always got and that was the price she named. But the merchant just laughed.

"Eh? What's that? I never gave such a price but to the Polevaya craftsmen Prokopich and his foster-son Danilo. But they were master craftsmen."

"I heard of it from them," she said. "I'm from the same family."

"So that's it," the merchant marvelled. "And I suppose that's things Danilo left wi' ye?"

"Nay," she said, "it's my own work."

"You'd some of his stone left, had ye?"

"I got the stone myself too."

You could see the merchant disbelieved her, but he didn't bargain. He settled with her honestly and even told her: "If you make more o' that kind, bring them here. I'll always take them and give ye a good price."

Katya went away real glad—fancy having all that money! The merchant put the brooches under the glass and buyers came running.

"How much?"

He hadn't cheated himself, of course—he asked ten times what he'd given, and kept telling folks: "You've never seen a pattern like that before. It's by Danilo the master craftsman of Polevaya. There's none better."

Katya came home in a daze.

Think of that, now! My brooches the best of them all! I happened on a good bit of stone. Luck favoured me... But then she suddenly thought:

What if it was a token from Danilushko?

As soon as she thought of that, she lost no time but hastened off to Serpent Hill.

Now, the malachite carver who'd wanted to make a fool of her before the merchant had got home too. And real envious he was, because Katya'd found such a rare pattern. I must see where she gets her stone, he thought. Maybe Prokopich or Danilo showed her some new place.

He saw Katya go running off somewhere, and set out after her. She went round one side of Gumeshky and somewhere up Serpent Hill. He followed, thinking to himself: It's all woods there. I'll be able to creep right up to the hole.

They entered the woods. He got quite close to Katya, but she never thought of anything, never looked back or stopped to listen. He was real glad to think he was going to get hold of a new place so easily. Then suddenly there was a noise off to the side, and he waited, a bit frightened. What could it be? And while he stood there listening, Katya disappeared. He started running, he blundered about in the woods all of a maze so he hardly found North Pond, about two versts from Gumeshky.

Katya never even dreamed anyone was watching her. She climbed up the hill, to the same spot where she'd found the first slab of stone. The hole seemed to have got bigger, and at the side she could see another slab like the first. She shook it and it moved, then seemed to snap off again like a twig. Katya picked up that stone, and then she started to weep and lament. Well, the way maids and wives do when their men have died, with all the words they can think of. "Where have you gone, why have you deserted me, my beloved?" and so on.

She cried a bit and felt better; then she stood thinking, looking over toward the mines. It was a sort of glade she was on. The trees were tall and thick all round, but between her and the mines they were smaller. It was sunset time. Down the slope the glade was dark from the thick woods, but the sun was still shining over where she looked. It was like as if it was on fire, and all the stones sparkled.

That seemed strange, and she wanted to go a bit closer. She moved her foot and something cracked under it. She pulled it back and looked down —and there was no ground under her. She was standing on a high tree, right on the very top. And there were other tree-tops like it all round her. In between them she could see grass and flowers down below, but they weren't the kind she knew.

Anyone else would have been real scared, started to shout and scream most likely, but Katya, she was thinking of something else.... It's opened, the mountain has. If only I could get a sight of Danilushko!

She'd no sooner thought it, than she saw someone coming through an opening in the trees; he was like Danilushko and he reached up his arms as if he wanted to say something. And Katya. she didn't think twice, she just threw herself down towards him—from the top of the tree!—well, and she fell right down there on the ground where she'd been standing before. So she pulled herself together, tried to tell herself sensibly: I must be seeing things. Better get home.

It was time to be going, that was right, but all the same she kept on sitting there, maybe the mountain would open again and she'd get another sight of Danilushko. So there she stopped till it was dark. At last she went home, but all the way she kept thinking: At last I've seen Danilushko.

That man who'd tried to follow her had got back again, and seen Katya's cottage was still shut up. So he hid himself and waited to find out what she'd bring. As soon as he saw her coming he put himself in her path.

"Where've ye been?" he asked her.

"To Serpent Hill."

"At night? What for?"

"To see Danilo."

The man started back, and next day there were whispers going round all over the village.

"The Dead Man's Bride's gone right off her head. Goes up Serpent Hill at night, looking for a man that's a corpse. What if she sets the whole place afire in a mad spell?"

Her brothers and sisters heard the talk and came hurrying to Katya again to scold her and argue with her. But she wouldn't listen to a word from them. She just showed them the money she'd got.

"Where d'ye think that's come from? There's good craftsmen whose work they don't take, but look what they paid me for the first I made! Why's that?"

They'd heard of her success, of course, and they told her: "Ye just had a bit o' luck. Nothing odd about that."

"Bits o' luck like that don't happen," she told them. "It was Danilo put the stone there for me and traced the pattern on it."

The brothers laughed, the sisters shrugged their shoulders.

"She's off her head! We ought to tell the bailiff or she really might burn us all down."

They didn't tell him, of course. They were ashamed to speak ill of their sister. But when they went out they agreed among themselves. "We'll have to watch her. Wherever she goes, someone must go after her at once."

Katya saw them to the door, fastened it after them, and set to work filing down the new piece of stone. She took it as a sign, what it would be like... If it's the same kind again, she thought, then I haven't been seeing things, it was really Danilushko there.

So she hurried with her work all she could. She wanted to see if there would be a real pattern. She kept on and on, right into the night. One of her sisters happened to waken, saw a light burning in the cottage, ran to the window and peeped in through a crack in the shutters. She gasped in amaze.

"Doesn't even sleep! It's awful, the way she is!"

Katya filed the slab through, and there was the pattern. It was actually better than the first. The bird was flying down from the tree, its wings spread out, and the other was flying up from the ground to meet it. Five times the pattern was repeated. And marked exactly where to cut it across. Katya didn't stop to think. She jumped up and ran out. The sister ran after her, knocking at the brothers' doors on the way—hurry, hurry, run! They dashed out, and other people came too. It was beginning to get light. They could see Katya run past Gumeshky. They all made after her, but she didn't even see folks were following her. She ran past the mine, and then went a bit slower round Serpent Hill. All the other people started going a bit slower too, they wanted to see what she'd do.

Katya went her usual way up the hill. She looked round her, and the woods seemed sort of strange. She touched a tree and it was cold and smooth like polished stone. And the grass under her feet was of stone too, and it was still dark here... I must be under the mountain, she thought.

Everyone was running about, they didn't know what to do. "Where's she gone? She was quite close, now she's vanished!" They ran here and there, all excited, calling: "Is she over there?"

But Katya was walking through the forest of stone, wondering how she could find Danilo. She walked and walked, and kept calling: "Danilo, where are ye?"

Her call echoed through the woods and the twigs knocked together saying: "Not here! Not here! Not here!" But Katya wouldn't give in.

"Danilo, where are ye?"

Again the trees answered: "Not here! Not here! Not here!"

And again Katya called: "Danilo, where are ye?"

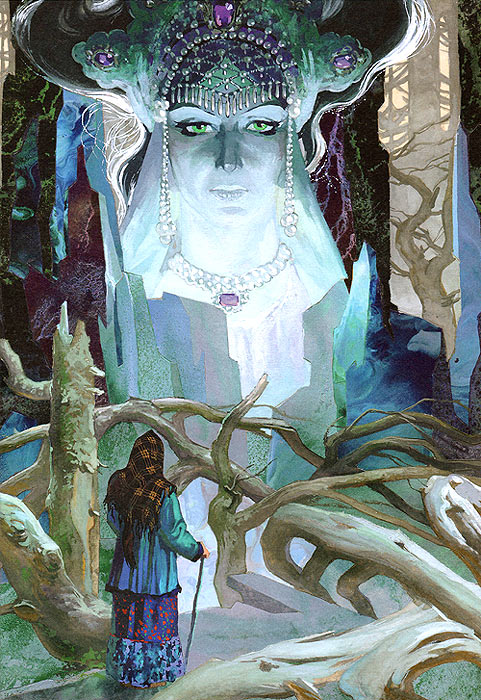

Then the Mistress of the Mountain suddenly appeared before her.

"Why have you come to my forest?" she asked. "What is it you want? Is it stone? Choose what you will, and go!"

But Katya answered: "I don't want your dead stone! Give me my living Danilushko! Where have ye hidden him? What right have ye to lure away another maid's sweetheart?"

She's got pluck, that maid. Set upon her right away. And it was the Mistress! But the Mistress, she just stood there quietly.

"What more have you to say?"

"Only one thing—give me Danilo! You've got him..."

The Mistress burst out laughing, and then she said: "Foolish maid, d'ye know who you're talking to?"

"I'm not blind," cried Katya. "I can see who ye are. But I'm not afeard ye, ye temptress! Not a mite! Cunning as ye are, still it's me Danilo thinks of. I've seen it myself. Ah—I've hit ye there!"

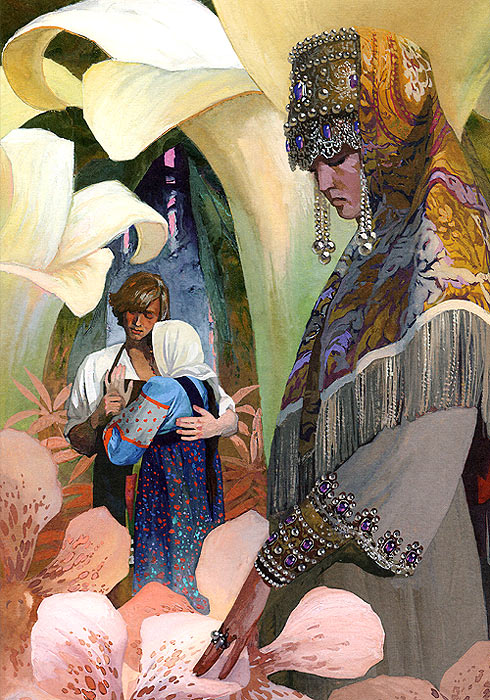

Then the Mistress said: "Let us hear what he says himself."

All the time the forest had been dark, but now it seemed to come alive. It got light, the grass sparkled all colours, and the trees—each one was more beautiful than the other. At the end of an opening there was a glade with flowers of stone growing on it, and golden bees like sparks flashing over them. It was all so beautiful, you could have looked an age and never wearied of looking. And then Katya saw Damilo come running through that forest. Straight to her. And she rushed to meet him.

"Danilushko!"

"Wait!" the Mistress commanded, and then she said: "Well, Danilo the Master Craftsman, now you must choose. If you go with her you forget all that is mine, if you remain here, then you must forget her and all living people."

"Living people," he said, "I can't forget, and her I remember every minute."

Then the Mistress smiled very sweetly.

"You have won, Katya! Take your craftsman. And for your wisdom and faith I have a gift for you. Let Danilo remember all he has learned here, only this—let him forget forever." And in an instant the glade and the marvellous flowers faded and vanished. "And now, go back to the outer world," said the Mistress, and warned him: "You, Danilo, say no word about the mountain. Tell them you went away to a master craftsman in far parts to learn his skill. And you, Katya, never dare think again I lured away your sweetheart. He came himself for that which he has now forgotten."

Then Katya bowed low.

"Forgive me my sharp words."

"Be it so," said the Mistress. "What can hurt stone? I say it for your sake, that you should not let your love cool."

Katya and Danilo walked through the forest; it was all dark and rough underfoot, with humps and holes. They looked round and found they were in the mine, under Gumeshky. It was still early, nobody was there. So they made their way quietly home. And all those who'd gone running after Katya were still in the woods calling: "Can you see her?" They searched and searched but couldn't find her, so they went back home, and there was Danilo sitting by the window.

They were real scared, of course. They got further away and started muttering prayers and spells together. But then they saw Danilo filling his pipe. Well, that settled it. A dead man wouldn't smoke a pipe, they thought.

They started coming up a little closer and a little closer, one by one. And there was Katya in the cottage, she was heating up the stove, as gay and happy as could be. It was long since they'd seen her like that. Then they got quite brave and went right into the cottage and started asking questions.

"Where've ye been all this time, Danilo?"

"I went to Kolyvan," he said, "I heard of a master craftsman, none there was with greater skill and art, folks said. I thought I'd go and learn a bit from him. Father, peace be to him, didn't want me to go. Well, so I made off without telling any. It was only Katya I told."

"But why," they said, "did ye smash that goblet o' yours?"

"Eh, all sorts of things happen," he said. "I'd just got home from the merrymaking... Mebbe I'd taken a drop too much... It hadn't turned out as I wanted, so I just took and smashed it. It can happen to anyone, a thing like that. Naught to talk about."

Then Katya's brothers and sisters started on her, why hadn't she told them about Kolyvan? But they didn't get much out of her either, only tart words.

"When other tongues clack, mine's still. Didn't I keep telling ye Danilo was alive! And what did ye do? Kept pushing suiters at me and trying to put me wrong. Come to table, my eggs are just fried."

So that was the end of it. They sat there a bit, her brothers and sisters, talking of this and that, and then went their ways. In the evening Danilo told the bailiff he was back. The man shouted and stormed a bit, of course, but it passed off all right.

So Danilo and Katya started living together in their cottage. Folks say they were happy, never a cross word. Danilo was always called the Mountain Craftsman because of his work, there was none could come near him. So they were well off. Only sometimes Danilo would get sort of thoughtful. Katya knew what he was thinking about, of course, but she said naught.

Author: Bazhov P.; illustrated by Nazaruk V.Please support us

PayPal: anfiskinamama@gmail.com

Contact us if you have any questions or see any mistakes

© 2019-2026 Freebooksforkids.net