|

Free Online Illustrated Books for Kids |

Popular Andersen Fairy Tales Animal Stories Poetry for Kids Short Stories Categories list

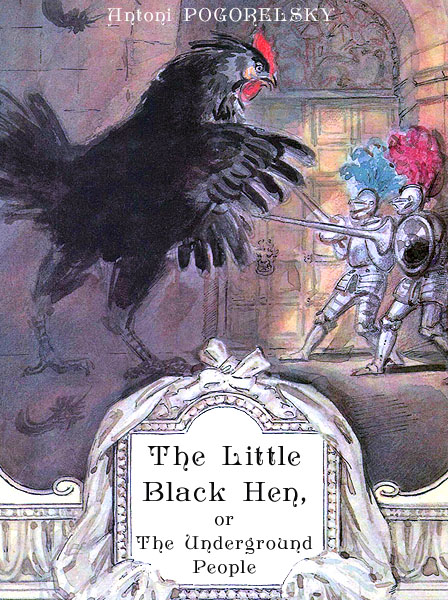

Antoni Pogorelsky

The Little Black Hen, or The Underground People

Translated by Kathleen Cook

freebooksforkids.net

Illustrated by A.Raypolsky

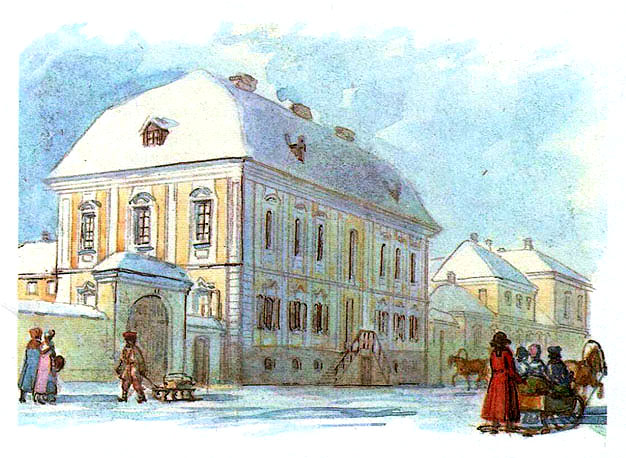

Some forty years ago in St Petersburg, in the First Line on Vassilievsky Island lived the master of a boarding school for boys which many will probably remember well to this day, although the building which the school occupied has long since made way for another bearing no resemblance to the earliest one. At that time St Petersburg was famed throughout Europe for its beauty, although it was nothing like what it is now. There were no delightful shady avenues on the prospects of Vassilievsky Island. In place of today’s fine pavements there were wooden planks, often rotten. St Isaac’s Bridge was narrow and crooked, and presented a very different appearance from now. In short, St Petersburg was not what it is today. Towns have the advantage over people that they occasionally grow more beautiful with the years. However, this is a digression. Some other time and on some other occasion I may perhaps speak in more detail about the changes that have taken place in St Petersburg during my lifetime, but now I shall turn once again to the boarding school which, some forty years ago, stood in the First Line on Vassilievsky Island.

The building which you will not find today was a two-storeyed one covered with Dutch tiles. The entrance porch was wooden and faced the street. From the lobby a fairly steep staircase led up to the second storey consisting of eight or nine rooms, where the boarding-school master lived on one side and there were classrooms on the other. The children’s dormitories were on the ground floor, on the right side of the lobby, and on the left lived two elderly Dutch ladies, both over a hundred years old, who had seen Peter the Great with their own eyes and even spoken to him.

Among the thirty or forty children in the boarding school was a boy named Alyosha, who could have been no more than nine or ten at the time. His parents, who lived far away from St Petersburg, had brought him to the capital two years earlier, delivered him to the boarding school and returned home, after paying the schoolmaster the necessary fees for several years in advance.

Alyosha was a nice clever boy, good at his lessons, and everyone was fond of him. In spite of this he was often lonely at the boarding school, however, and sometimes even sad as well. Particularly at the beginning he could not get used to the idea that he was parted from his parents. But then he gradually grew accustomed to his position, and there were even moments when, playing with his friends, he thought it was more fun in the boarding school than in his parents’ house.

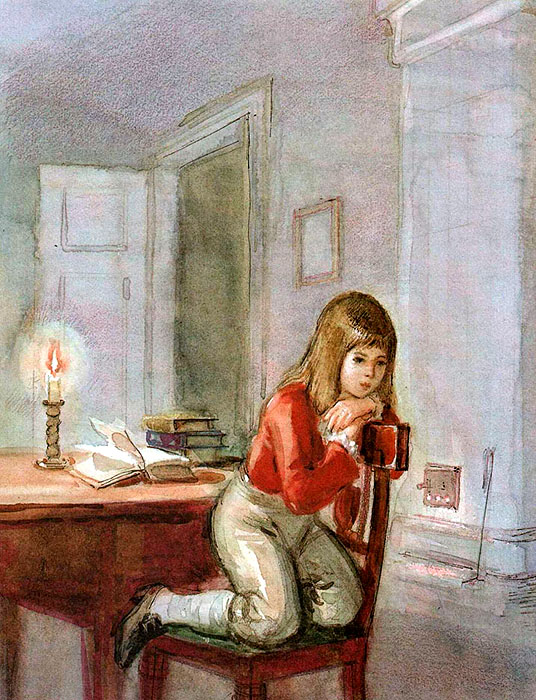

In general the days of learning passed quickly and pleasantly for him, but when Saturday came and his friends hurried home to their families, Alyosha felt his solitude bitterly. On Sundays and holidays he was alone all the time, and then his only comfort was reading the books which the schoolmaster allowed him to borrow from his small library. At that time the fashion in literature was for tales of chivalry and fairy stories, and the library which Alyosha used consisted mostly of books of this kind.

So by the age of ten, Alyosha was already well acquainted with the deeds of the most famous knights, at least as they were described in novels. His favourite occupation in the long winter evenings, on Sundays and other holidays was to imagine himself in bygone ages... Especially during the vacations, when he was parted from his school-fellows for a long time and often spent whole days on his own, his young imagination would wander through knight’s castles, terrible ruins or dark dense forests.

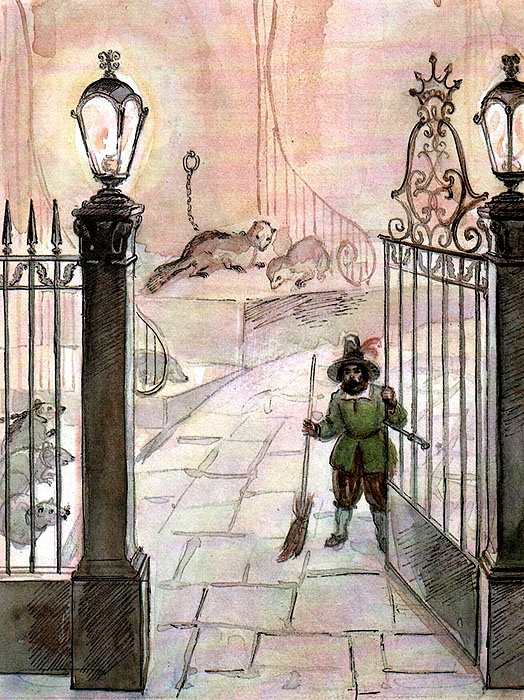

I have forgotten to tell you that the house had a rather large courtyard which was separated from the alley by a wooden fence of barge planks. The gate and wicket that led into the alley were always locked, and so Alyosha had never been able to go into the alley which strongly excited his imagination. Every time he was allowed to play in the courtyard in his recreation periods, the first thing he did was to run up to the fence. He would stand there on tiptoe, staring through the round holes in the fence. Alyosha did not know that these holes were from wooden nails used to make barges, and he thought that a good fairy had made them just for him. He kept waiting for the fairy to appear in the alley and hand him a toy or a talisman through a hole, or a letter from his father or mother from whom he had not received any news for a long time. But to his extreme regret no one even vaguely resembling a fairy appeared.

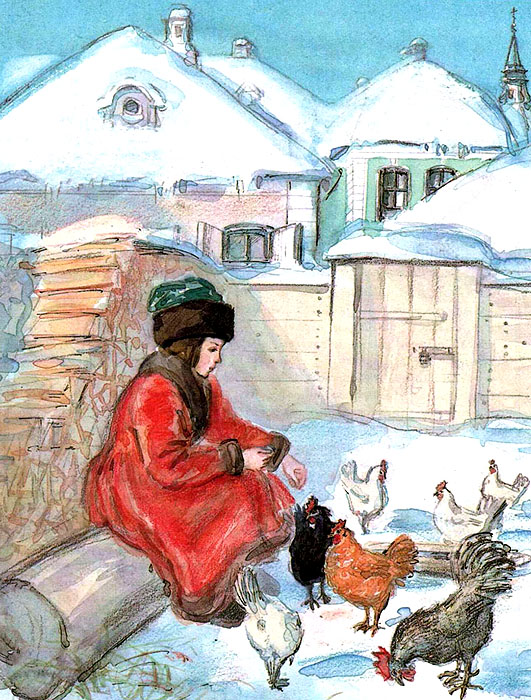

Another of Alyosha’s occupations was to feed the hens, who lived by the fence in a small house specially built for them and played and ran about all day in the yard. Alyosha very soon made their acquaintance, knew them all by name, broke up their fights, and punished the trouble-makers by depriving them for several days of the crumbs that he brushed off the tablecloth after dinner and supper. Of all the hens he was particularly fond of a black crested one called Blackie. Blackie showed more affection for him than all the others: she even allowed him to stroke her sometimes, so Alyosha kept the best pieces for her. She was of a quiet disposition, rarely strutted with the others, and seemed to be fonder of Alyosha than of all her friends.

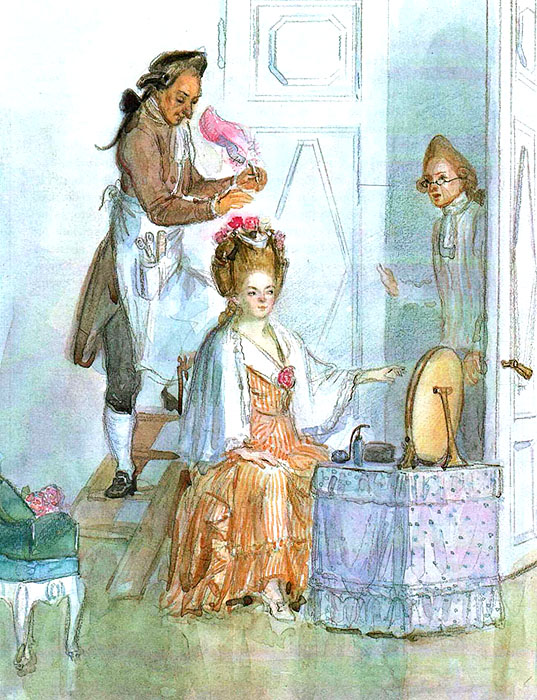

Once (it was during the winter vacations), on a fine and unusually warm day, Alyosha was allowed to play outside. The schoolmaster and his wife were very busy that day. They were having the inspector of the schools to dinner, and so the day before they had spent from dawn to dusk scrubbing floors, dusting and polishing mahogany tables and dressers. The schoolmaster himself went to purchase provisions for the table: white Archangel veal, a huge ham and candied fruit. Alyosha also did what he could to help with the preparations: they made him cut a pretty frill of white paper for the ham and decorate with paper patterns the six wax candles specially bought for the occasion. On the appointed day the hairdresser appeared early in the morning and demonstrated his art on the schoolmaster’s boucles, toupet and long plait. Then he turned his attentions to the schoolmaster’s wife, pomaded and powdered her ringlets, and piled a whole hothouse of different flowers on her head, among which flashed two well-placed diamond signet rings, which her husband had been given by pupils’ parents. When her hair had been dressed, she put on an old dressing gown and went about her household duties, while making sure that her coiffure was not spoilt. To this end she did not go into the kitchen, but stood at the doorway and gave instructions to her cook. In cases of necessity she sent her husband in there, whose coiffure was not so high.

In the course of all these activities Alyosha was completely forgotten, and he took advantage of the fact to play outside in the yard. As was his custom, he first went up to the wooden fence and spent a long time looking through a hole; but as usual hardly anyone walked along the alley, and he turned with a sigh to his beloved hens. No sooner had he sat down on a log and started calling them to him, when he saw the cook beside him with a big knife. Alyosha had never liked the cook — a bad-tempered, sharp-tongued woman. But ever since he had noticed that she was the reason why his hens dropped in number from time to time, he liked her even less. And when one day he had happened to see in the kitchen his favourite cockerel hanging by the legs with its throat cut, he felt fear and revulsion for her. Seeing her now with the knife, he immediately guessed what it meant and, realising bitterly that he was unable to help his friends, jumped up and ran a long way off.

“Alyosha! Alyosha! Help me catch a hen!” shouted the cook.

But Alyosha only ran faster, hid by the fence behind the hen-house and did not notice the tears rolling out of his eyes and falling on the ground.

He stood by the hen-house for quite a long time, his heart beating hard, while the cook ran round the yard, sometimes calling the hens, sometimes scolding them.

Suddenly Alyosha’s heart beat harder than ever: he heard the voice of his beloved Blackie. She was clucking desperately and he seemed to hear her say:

|

Cluck, cluck, clucky! |

Alyosha could stay where he was no longer. Sobbing loudly, he rushed to the cook and threw himself on her neck just as she had grabbed Blackie by the wing.

“Dear, nice Trinushka!” he exclaimed, the tears pouring down his cheeks. “Please don’t touch my Blackie!”

Alyosha had caught hold of the cook’s neck so unexpectedly, that she let go of Blackie, who took advantage of this to fly up in fright to the roof of the shed, where she continued to cluck. But Alyosha now seemed to hear her teasing the cook and shouting:

|

Cluck, cluck, clucky! |

Meanwhile the cook was beside herself with rage and wanted to tell the schoolmaster, but Alyosha would not let her go. He caught hold of her dress and began to plea so touchingly that she stopped.

“Dear Trinushka!” he said. “You’re so good, nice and kind... Please leave my Blackie alone! Look what I’ll give you, if you do.”

Out of his pocket Alyosha drew an old goldpiece, his most treasured possession, because it was a present from his grandmother. The cook looked at the coin, glanced at the windows of the house to make sure that no one could see, and stretched out a hand for the coin. Alyosha was very sorry to part with it, but he remembered about Blackie and handed over the precious gift resolutely.

Thus Blackie was saved from a cruel and certain death.

As soon as the cook retired to the house, Blackie flew down from the roof and ran up to Alyosha. She seemed to know that he was her deliverer: she ran around him, flapping her wings and clucking joyfully. All morning she followed him round the yard, like a dog, as if she wanted to tell him something, but could not. At least he could not make out her clucking.

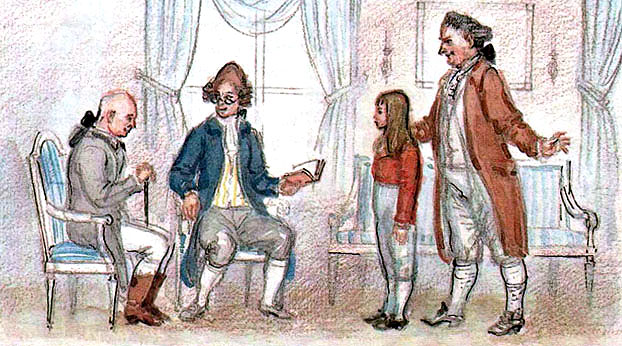

Two hours or so before dinner the guests began to arrive. Alyosha was summoned upstairs and dressed in a shirt with a round collar and pleated lawn cuffs, white pantaloons, and a broad blue silk sash. His long fair hair, which almost reached his waist, was well combed, divided into two equal bunches and draped on either side of his chest. That was the fashion for children in those days.

Then he was told how to click his heels when the inspector came into the room and what to say if he were asked any questions.

Any other time Alyosha would have been pleased at the arrival of the inspector, whom he wanted to see very much because, judging by the respect with which the schoolmaster and his wife spoke of him, he imagined that he must be a famous knight in shining armour and a plumed helmet. But this time his curiosity gave way to the thoughts that were preoccupying him: about the black hen. He kept imagining the cook chasing her with a knife and Blackie clucking for all she was worth. He was most vexed at not being able to understand what she was trying to tell him, and he longed to go to the hen-house... But there was nothing for it: he must wait until dinner was over.

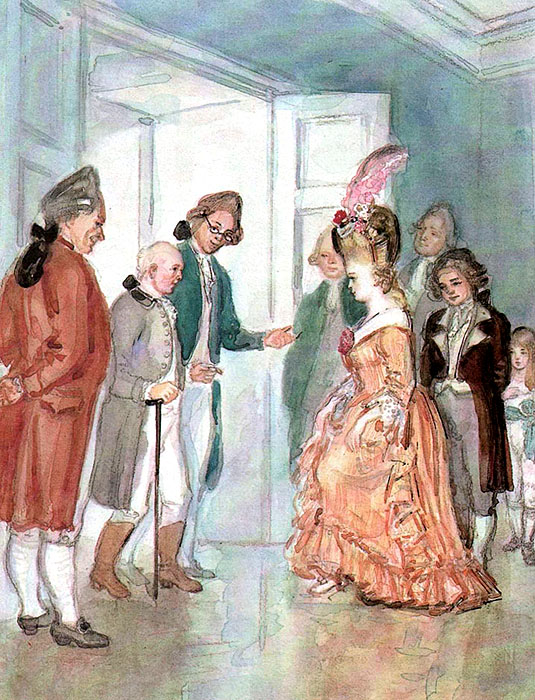

At last the inspector arrived. His arrival was announced by the schoolmaster’s wife who had been sitting by the window, staring in the direction from which he was expected.

Everything went into motion: the schoolmaster sped out of the door to meet him below, by the porch, and the visitors rose from their seats. Even Alyosha forgot about his hen for a moment and went to the window to watch the knight getting off his noble charger. But he did not manage to see him: the inspector had already entered the house. By the porch, instead of a noble charger, stood an ordinary passenger sledge. Alyosha was very surprised. “If I were a knight,” he thought, “I would never ride in a sledge, only on horseback!”

Meanwhile the doors were thrown wide open, and the schoolmaster’s wife began a slow curtsey in expectation of the highly respected guest, who duly appeared shortly afterwards. At first he was hidden by the fat schoolmaster’s wife, who was standing in the doorway; but when she finished her long greeting, curtseying lower than usual, Alyosha saw behind her to his extreme astonishment... not a plumed helmet, but a small baldish head, powdered white, and adorned only, as Alyosha noted later, by a small pigtail! When he entered the drawing room, Alyosha was even more surprised to see that, in spite of the simple grey tail-coat, which the inspector wore instead of shining armour, everyone treated him with the greatest of respect.

However strange all this seemed to Alyosha, however delighted he would have been at any other time by the unusually rich fare on the table, today he paid little attention to it. His small head was still full of what had happened that morning with Blackie. The dessert was served: preserves, apples, pears, figs, grapes and walnuts; but even now he did not stop thinking about his hen for a moment. And as soon as they rose from the table, he went up to the schoolmaster, his heart trembling with fear and hope, and asked if he might go out to play in the yard.

“You may,” the schoolmaster replied, “but do not stay there long: it will soon be dark.”

Alyosha hastily donned his red overcoat lined with squirrel fur and his green velvet cap trimmed with sable and ran to the fence. When he got there, the hens were beginning to settle down for the night. They were sleepy and not very pleased with the crumbs he had brought them. Only Blackie seemed to have no desire to sleep: she ran up to him, flapped her wings and began to cluck again. Alyosha played with her for a long time; eventually, when it got dark and was time to go home, he locked the hen-house himself, having made sure that his beloved Blackie was settled on the perch. As he was leaving, he seemed to see her eyes shining in the darkness like stars and hear her saying softly:

“Alyosha! Alyosha! Stay with me!”

Alyosha returned to the house and sat alone all evening in the classrooms, while the guests stayed until past ten in the other half of the house. Before they had all left, Alyosha went down to his bedroom in the lower storey, undressed, climbed into bed and put out the light. He could not get to sleep for a long time. Finally sleep overcame him, and he had just managed to start talking to Blackie in a dream when, unfortunately, he was awakened by the sound of the departing guests.

A little later the schoolmaster, having seen the inspector to his sledge with a candle, came into the dormitory, looked around to make sure that all was in order, and left, locking the door behind him.

It was a moon-lit night, and a pale moonbeam shone into the room through the lightly closed shutters. Alyosha lay with open eyes and listened for a long time to them walking about upstairs tidying the chairs and tables.

At last all was quiet. He looked at the bed next to his, slightly lit by moonlight, and noticed that the white sheet hanging almost to the floor, was moving slightly. He began to stare at it... then he heard something scratching under the sheet, and a little later a voice seemed to call him quietly:

“Alyosha! Alyosha!”

Alyosha was afraid. He was alone in the room, and immediately thought there must be a robber under the bed. But then he reasoned that a robber would not call him by his name, and cheered up slightly, although his heart was trembling. Sitting up in bed, he saw that the sheet really was moving... and heard someone say quite clearly:

“Alyosha! Alyosha!”

Suddenly the white sheet rose up, and from behind it appeared... the black hen!

“Oh! It’s you, Blackie!” Alyosha exclaimed. “How did you get in here?”

Blackie flapped her wings, flew up onto his bed and said in a human voice:

“It’s me, Alyosha! You’re not afraid of me, are you?”

“Why should I be afraid of you?” he replied. “I love you; only I’m surprised that you can speak so well: I did not know that you could speak!”

“If you are not afraid of me,” the hen continued, “come with me now. Get dressed quickly!”

“You are funny, Blackie!” said Alyosha. “How can I get dressed in the dark? I won’t be able to find my clothes. I can barely see you!”

“I will try to help,” said the hen.

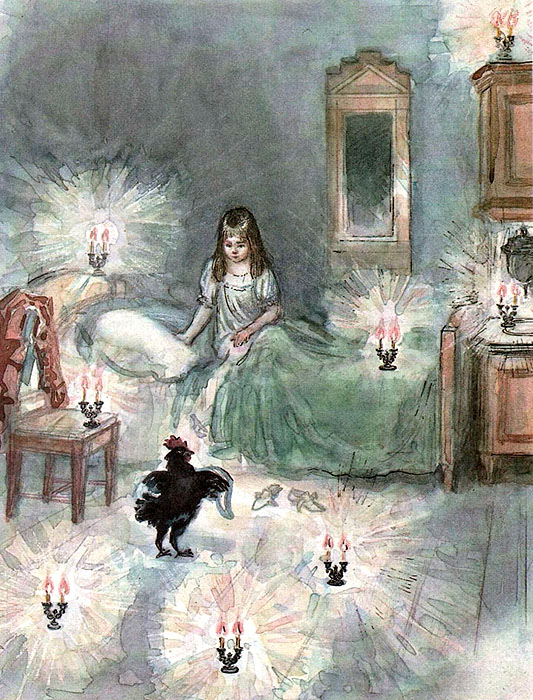

Then she clucked in a strange voice, and suddenly small candles in silver candlesticks, no larger than Alyosha’s little finger, appeared from nowhere. There were candlesticks on the floor, the chairs, the windows, and even the wash-basin, and it became as light as day in the room. Alyosha began to get dressed, and the hen handed him his clothes, so he was soon fully dressed.

When Alyosha was ready, Blackie clucked again and the candles disappeared.

“Follow me!” she told him.

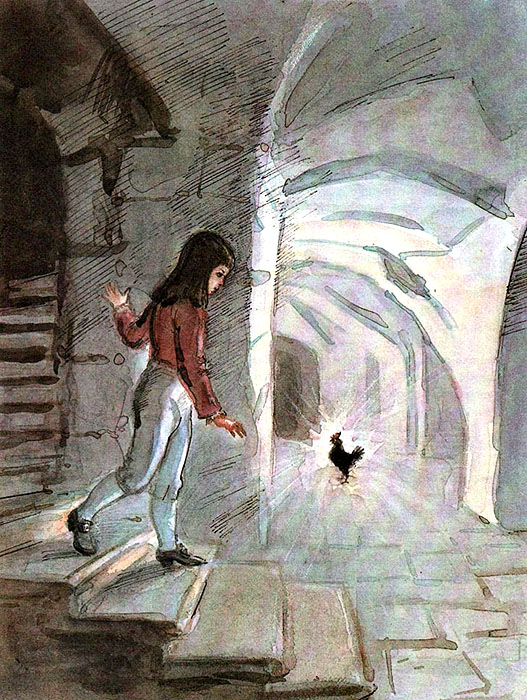

He followed her bravely. Beams seemed to come from her eyes and light up everything around them, although not as brightly as the small candles. They went through the hall.

“The door is locked,” said Alyosha.

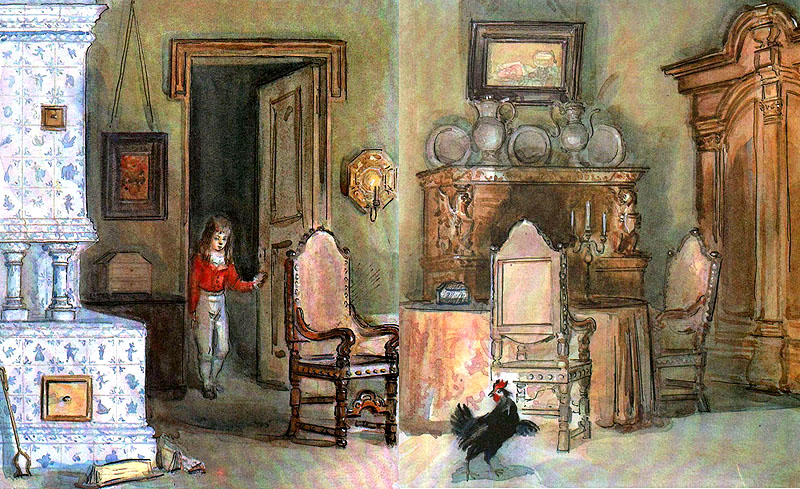

But the hen did not answer him: she flapped her wings, and the door opened by itself. Then they walked through the lobby and turned towards the rooms where the hundred-year-old Dutch ladies lived. Alyosha had never been there, but had heard that their rooms were furnished in old-fashioned style, and that one of them had a big grey parrot and the other a grey cat, a very clever one that could jump through a hoop and give its paw. He had always wanted to see all this, so he was very glad when the hen flapped her wings again and the old ladies’ door opened.

In the first room Alyosha saw all sorts of old furniture: carved chairs, armchairs, tables and dressers. There was a big stove of Dutch tiles with people and animals painted on it in blue. Alyosha wanted to stop and look at the furniture, especially the figures on the stove, but Blackie would not let him.

They entered the second room, and Alyosha was delighted! In a splendid gold cage sat a big grey parrot with a red tail. Alyosha wanted to run up to it at once. Again Blackie would not let him.

“Don’t touch anything here,” she said. “Be sure not to wake the old ladies!”

Only then did Alyosha notice that beside the parrot was a bed with white muslin curtains, through which he could make out an old lady lying with eyes closed; she looked as if she were made of wax. In another corner was an identical bed where the other old lady was sleeping, and next to her sat a grey cat, washing itself with front paws. As he walked past, Alyosha just had to ask for its paw... It began to mew loudly, and the parrot raised its crest and squawked: “Silly fool!” He could see the old ladies sit up in bed behind the muslin curtains. Blackie ran away hastily, followed by Alyosha. The door slammed hard behind them... and for a long time they could hear the parrot squawking: “Silly fool! Silly fool!”

“You should be ashamed of yourself!” said Blackie, when they had left the old ladies’ chambers. “You’ve probably woken the knights...”

“What knights?” asked Alyosha.

“You’ll see,” the hen replied. “Don’t be afraid, though, it doesn’t matter, follow me boldly.”

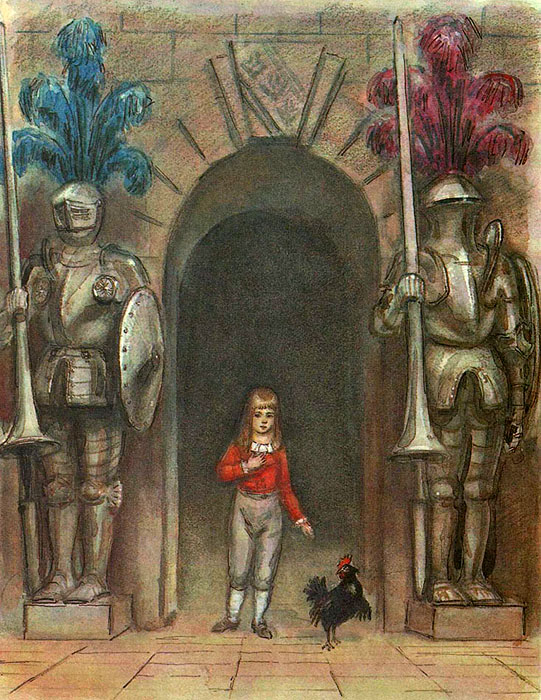

They descended the staircase into a kind of cellar, and walked along various passages and corridors that Alyosha had never seen before. Sometimes the corridors were so low and narrow, that Alyosha had to bend down. Suddenly they entered a large hall lit by three large crystal chandeliers. The hall had no windows. Hanging on the walls on either side of it were knights wearing shining armour and plumed helmets and holding spears and shields.

Blackie walked ahead on tiptoe and told Alyosha to follow her very quietly.

At the end of the hall was a large door of bright yellow brass. No sooner had they gone up to it, than two knights jumped off the wall, banged their spears on their shields and made for the black hen. Blackie raised her crest, spread out her wings... and grew bigger and bigger, taller than the knights, and began to fight them. The knights pressed her hard, but she defended herself with her wings and beak. Alyosha was very frightened, his heart trembled violently, and he fell into a faint.

When he came to the sun was shining through the shutters and he was lying in his bed. There was no sign of Blackie or the knights. Alyosha could not collect his thoughts for a long time. He did not know what had happened to him that night: had he dreamed it or had it really happened? He dressed and went upstairs, but could not forget what he had seen the night before. He waited impatiently for the time when he could go and play in the yard, but as luck would have it that day it was snowing hard and there could be no thought of going outside.

After dinner the schoolmaster’s wife informed her husband, among other things, that the black hen was not to be seen.

“Never mind,” she added, “it would not matter greatly if she did disappear: she’s been down for the pot for a long time. Just imagine, my dear, she has not laid a single egg ever since we got her.”

Alyosha nearly burst out crying, although it occurred to him that it would be better if she was not found, than if she ended up in the pot.

After dinner Alyosha remained alone in the classrooms again. He kept thinking about what had happened last night, and could not get over the loss of his beloved Blackie. Sometimes he felt sure he would see her the next night, although she had disappeared from the hen-house. But then he thought that was impossible, and his spirits sank again.

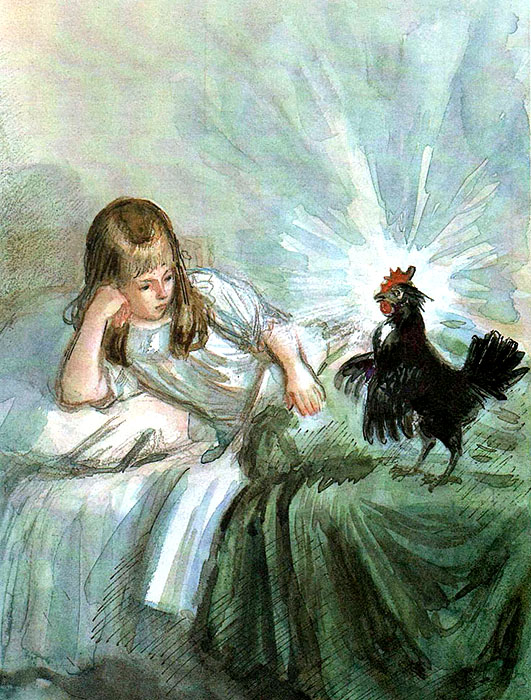

The time came to go to bed, and Alyosha undressed impatiently and lay down. No sooner did he look at the neighbouring bed, again bathed in pale moonlight, than the white sheet stirred as it had the day before... Again he heard a voice calling him: “Alyosha! Alyosha!” and a little later Blackie came out from under the bed and flew onto his bedclothes.

“Oh! Hello, Blackie!” he shouted, beside himself with joy. “I was afraid I would never see you again. Are you alright?”

“Yes,” the hen replied, “but I had a narrow escape thanks to you.”

“What do you mean, Blackie?” asked Alyosha, in alarm.

“You’re a good boy,” the hen continued, “but you’re impetuous and never do what you are told straightaway, and that’s bad. Yesterday I told you not to touch anything in the old ladies’ rooms, but in spite of that you had to ask the cat for its paw. The cat woke the parrot, the parrot woke the old ladies, the old ladies woke the knights — and I only just managed to deal with them.”

“I’m sorry, dear Blackie. I won’t do it again! Please take me back today. I’ll be good, you’ll see.”

“Alright,” said the hen, “we’ll see!”

The hen clucked as she had yesterday, and the same small candles appeared in the same silver candlesticks. Alyosha dressed and followed her. They again entered the old ladies’ rooms, but this time he did not touch anything.

As they were passing through the first room, the people and animals painted on the stove seemed to be making funny faces and trying to attract his attention, but he deliberately turned away from them. In the second room the old Dutch ladies were lying in bed, as before, looking as if they were made of wax. The parrot looked at Alyosha and blinked, the grey cat was washing herself with her paws. On a table in front of a mirror Alyosha saw two Chinese porcelain dolls, which he had not noticed the day before. They were nodding to him; he remembered Blackie’s instructions and walked past without stopping; but he could not resist bowing to them in passing. The dolls jumped off the table and ran after him, still nodding their heads. He was about to stop, for they seemed so amusing, but Blackie turned and gave him such an angry look that he thought better of it. The dolls accompanied them to the doors, and, seeing that Alyosha was not looking at them, returned to their places.

Again they descended the staircase, walked along passages and corridors and arrived at the hall, lit by three crystal chandeliers. The knights were hanging on the walls, and again, when they came to the brass door, two knights came from the wall and blocked their way. But they did not look as angry as the day before; they could hardly drag themselves along, like flies in autumn, and they barely had the strength to hold their spears.

Blackie grew bigger and bigger and raised her crest. But as soon as she struck them with her wings, they fell to pieces, and Alyosha saw that they were empty suits of armour! The brass door opened by itself and they walked on.

A little later they entered another hall, large but so low that Alyosha could touch the ceiling. This hall was lit by the small candles he had seen in his room, but the candlesticks were gold, instead of silver.

Then Blackie left Alyosha.

“Stay here for a little while,” she said to him, “I will be back soon. You were good today, although you were careless enough to bow to the porcelain dolls. If you had not bowed to them, the knights would have stayed on the wall. But you did not waken the old ladies today, and so the knights had no strength.” After which Blackie left the hall.

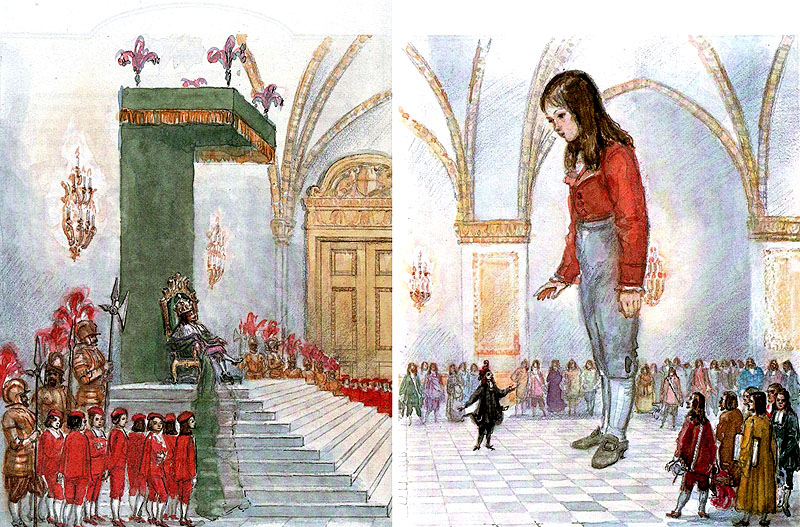

Left alone, Alyosha began to study the hall, which was very richly furnished. He thought the walls were made of marble that he had seen in the mineral cabinet at school. The panelling and doors were of pure gold. At the end of the hall, under a green canopy, on a raised platform, stood a chair of gold. Alyosha admired this furnishing, but thought it strange that everything was so small, as if for tiny toys.

While he was examining everything curiously, a side door, which he had not noticed before, opened and in came a lot of tiny people, about a foot tall, in splendid clothes. They looked most impressive: judging by their attire, some were military men, others public officials. All of them wore round feathered hats that looked Spanish. They did not notice Alyosha, and promenaded solemnly up and down the rooms, talking loudly among themselves, but he could not understand what they were saying. He watched them in silence for a long time and was about to go up and ask one of them a question, when the big door at the end of the hall opened... Everyone fell silent, lined up in double file by the walls and took off their hats.

In an instant the room grew brighter, the small candles burned brighter still, and Alyosha saw twenty small knights in gold armour, with crimson-plumed helmets, march quietly into the hall in pairs. They stood on either side of the chair in silence. A little later a man with regal bearing and a crown shining with precious stones on his head came into the hall. He wore a light-green mantle lined with mouse fur with a long train carried by twenty small pages in crimson suits.

Alyosha realised that this must be the king. He gave him a low bow. The King responded to his bow most graciously and sat down on the gold chair. Then he gave an order to one of the knights standing by him, who came up to Alyosha and told him to approach the chair. Alyosha obeyed.

“I have known for some time,” said the King, “that you are a good kind boy; but the day before yesterday you rendered a great service to my people and deserve a reward for it. My Head Minister has informed me that you saved him from a certain and cruel death.”

“When?” asked Alyosha in surprise.

“The day before yesterday in the yard,” replied the King. “Here is the man who owes his life to you.”

Alyosha looked at the person whom the King had pointed out, and only then noticed that among the courtiers was a small man dressed all in black. On his head was a special kind of crimson cap, serrated on top, worn slightly to one side, and round his neck a white necktie, stiffly starched, which gave it a slightly bluish tinge. He smiled gratefully, as he looked at Alyosha, who thought his face familiar, but could not remember where he had seen it.

Although highly flattered at having such a noble action attributed to him, Alyosha loved the truth and therefore, bowing low, said:

“Sire! I cannot let myself be credited with something I have not done. The day before yesterday I had the good fortune to save from death not your minister, but our little black hen, whom the cook did not like because she had never laid a single egg...”

“What are you saying!” the King interrupted him angrily. “My minister is not a hen, but an honoured official!”

The Minister came closer, and Alyosha saw that it was indeed his dear Blackie. He was overjoyed and begged the King’s pardon, although he could not understand what it all meant.

“Tell me what you would like,” the King continued. “If it is within my power, I shall grant your request.”

“Don’t be afraid, Alyosha!” the Minister whispered in his ear.

Alyosha thought hard and did not know what to ask for. Had he been given more time, he might have thought of something good. But since he considered it discourteous to make the King wait, he gave a hasty reply.

“I wish,” he said, “that I could always know the lessons I have been set without learning them.”

“I did not think you were so lazy,” the King replied, shaking his head. “But I must grant your wish nevertheless.”

He waved his hand, and a page brought a gold plate on which lay a single hemp seed.

“Take this seed,” said the King. “As long as you have it, you will always know whatever lesson has been set you, on the sole condition that you never, under the slightest pretext, say a single word about what you have seen or will see here. The slightest indiscretion will deprive you forever of our favour, and will cause us much trouble and unpleasantness.”

Alyosha took the hemp seed, wrapped it in a piece of paper and put it in his pocket, promising to be silent and discreet. Whereupon the King rose from the armchair and left the hall with the same ceremony, after ordering the Minister to entertain Alyosha in the best possible style.

No sooner had the King retired, than all the courtiers crowded round Alyosha and made a fuss of him, expressing their gratitude to him for saving the Minister. They all offered him their services: some asked if he would care to take a walk in the garden or look at the Royal Menagerie; others invited him to go hunting. Alyosha did not know what to choose. Finally the Minister announced that he himself would show the underground wonders to the dear guest.

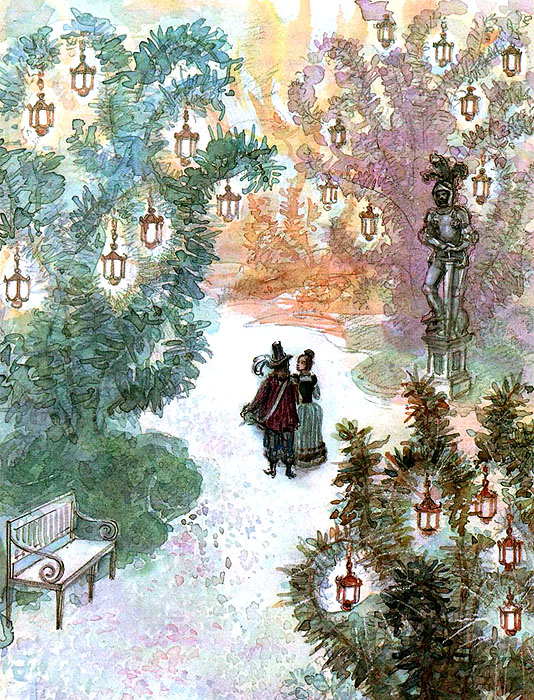

First he took him into the garden. The paths were strewn with coloured stones that reflected the light of the countless small lanterns hanging on the trees. The shining pleased Alyosha greatly.

“These stones are what you call gems,” said the Minister. “They are diamonds, rubies, emeralds and amethysts.”

“Oh, I wish our paths were strewn with them!” Alyosha exclaimed.

“Then they would be of as little value to you as they are here,” replied the Minister.

The trees also looked extremely beautiful to Alyosha, although very strange. They were of different colours: red, green, brown, white, blue and violet. Examining them carefully, he saw that they were actually different sorts of moss, only taller and thicker than usual. The Minister told him that the King had paid a lot of money to have this moss brought from far countries and from the very depths of the earth.

From the gardens they went into the menagerie. Here Alyosha was shown wild animals on gold chains. Inspecting them more closely, he found to his surprise that they were large rats, moles, ferrets and suchlike animals who live under the ground and the floor. He thought this most amusing, but said nothing out of courtesy.

Returning to the rooms after the walk, Alyosha found a table set with all manner of confitures, pies, pate, and fruit in the big hall. The dishes were made of pure gold, and the goblets and glasses were fashioned from diamonds, rubies and emeralds.

“Eat what you like,” said the Minister, “you are not allowed to take anything with you.”

Alyosha had eaten a good supper that day, so he did not feel in the least hungry.

“You promised to take me hunting,” he said.

“Very well,” the Minister replied. “I think the horses are saddled.”

He whistled and grooms came in, leading hobby horses with carved heads by the reins. The Minister jumped onto his horse with great agility. Alyosha was given a hobby horse much bigger than the rest.

“Mind the horse does not throw you,” said the Minister, “she’s not one of the quietest.”

Alyosha smiled inwardly at this, but when he took the hobby horse between his legs, he saw that the Minister’s advice was not in vain. The stick began to twist and turn under him like a real horse, and he only remained in the saddle with difficulty.

Meanwhile there was a fanfare of horns, and the hunters began to gallop at full speed down the passage's and corridors. They galloped like this for some time, and Alyosha did not lag behind them, although he could only restrain his bucking stick with difficulty.

Suddenly some rats bigger than any Alyosha had ever seen sprang out of a side corridor. They wanted to run past, but when the Minister ordered them to be surrounded, they stopped and defended themselves bravely. In spite of this, however, they were vanquished by the courage and skill of the hunters. Eight rats lay on the ground, three were put to flight, and another, a rather badly wounded one, the Minister ordered to be treated and sent to the menagerie.

After the hunting Alyosha was so tired that his eyes kept closing. Notwithstanding this he had a lot to say to Blackie, and asked permission to return to the hall from which they had set out hunting. The Minister agreed.

They set off back at the gallop and arriving in the hall, handed the horses over to the grooms, bowed to the courtiers and hunters, and sat down next to each other on the chairs brought for them.

“Tell me, please,” Alyosha began, “why did you kill the poor things who were not disturbing you and live so far from your dwellings?”

“If we had not destroyed them,” said the Minister, “they would soon have driven us out of our abode and destroyed all our provisions. What is more, mouse and rat fur is very expensive here because it is light and soft. Only the nobility is allowed to wear it.”

“And please tell me who you are,” Alyosha continued.

“Haven’t you ever heard that our people live under the ground?” replied the Minister. “True, few ever succeed in seeing us, but there have been cases, particularly in the old days, when we went out and showed ourselves to people. That rarely happens now, because people have grown very indiscreet. And we have a law that if the person to whom we have shown ourselves does not keep it a secret, we have to leave our abode at once and go far, far away, to other lands. As you can easily imagine, it would be most unpleasant for our King to leave all the establishments here and move to unknown lands with all the people. Therefore I would beg you most earnestly to be as discreet as possible. Otherwise you will make us all unhappy, particularly me. Out of gratitude I requested the King to summon you here; but he would never forgive me, if we are compelled to leave these parts because of your indiscretion...”

“I give you my word that I shall never speak of you to anyone.” Alyosha interrupted him. “I have remembered now what I read in a book about gnomes who live under the earth. They say that in a certain town a shoemaker grew very rich in a short time, and no one could understand where his wealth came from. At last they found out that he made boots and shoes for gnomes who paid him most handsomely for it.”

“It may be true,” replied the Minister.

“But, tell me, dear Blackie,” Alyosha asked him, “why did you, a minister, appear in the form of a hen and what connection do you have with the old Dutch ladies?”

Desiring to satisfy his curiosity, Blackie was about to relate much to him in detail, but as soon as she started Alyosha’s eyes closed and he fell fast asleep. When he awoke next morning he was in his own bed.

For a long time he was confused and did not know what to think. Blackie and the Minister, the King and the knights, the Dutch ladies and the rats — everything was mixed up in his head, and he had difficulty in sorting out in his mind all that he had seen the night before. Remembering that the King had given him a hemp seed, he hurriedly ran to his suit and found in the pocket the piece of paper in which the hemp seed was wrapped. “Now we shall see if the King keeps his word!” he thought. “Lessons begin tomorrow, and I have not done all my homework yet.”

The history lesson worried him in particular: he had been given several pages of history to learn by heart, and he did not know a single word!

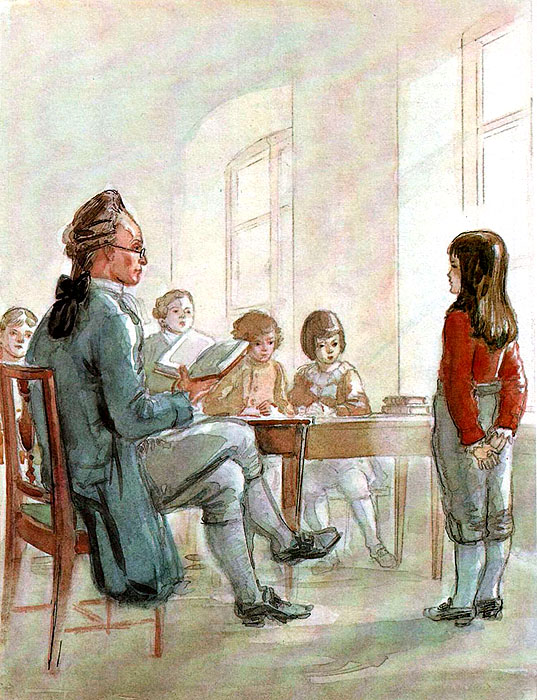

Monday arrived, the pupils came back, and lessons began. The master of the boarding school himself taught history from ten to twelve.

Alyosha’s heart was beating fast... Waiting for his turn, he fingered the piece of paper with the hemp seed several times in his pocket... Eventually he was called out. In fear and trembling he went up to the schoolmaster, opened his mouth, not knowing what to say, and recited all the pages straight off without a single mistake. The schoolmaster lavished him with praise; but Alyosha did not feel the same pleasure at his praise as he had felt before in similar situations. A voice inside him said that he did not deserve it, because he had not taken any pains to learn the lesson.

For several weeks the teachers could not praise Alyosha enough. All lessons without exception he knew perfectly, all his translations from one language into another were faultless, so that they could not help but marvel at his extraordinary prowess. Deep down Alyosha was ashamed of this praise: his conscience pricked him at being set up as an example to his classmates, when he did not deserve it.

All this time Blackie did not appear, in spite of the fact that Alyosha, particularly in the first few weeks after he received the hemp seed, let hardly a day pass without calling her when he went to bed. At first he was grieved by this, but then calmed down, thinking that she was probably engaged in some important business in keeping with her vocation. Later he found the praise lavished upon him so diverting that he remembered her only rarely.

Meanwhile rumours of his unusual abilities spread quickly all over St Petersburg. The inspector of the schools visited the school several times to admire Alyosha. The schoolmaster thought the earth of him, because he had made his school famous. Parents came from all over the town, begging him to take their children in the hope that they would be as clever as Alyosha.

Soon the school was so full that there was no room for new pupils, and the schoolmaster and his wife began to think about renting a more spacious house than the one in which they lived.

Alyosha, as I have already mentioned above, was ashamed of the praise at first, feeling that he did not deserve it, but gradually he grew accustomed to it, and eventually became so conceited that he accepted the praise lavished upon him without turning a hair. He began to think a lot of himself, showed off in front of the other boys and imagined that he was better and cleverer than all of them. As a result his character was quite spoiled: from a good, nice and modest boy he turned into an arrogant, disobedient one. His conscience often reproached him with this, and a voice inside him said: “Do not be proud, Alyosha! Do not attribute to yourself that which does not belong to you; thank fortune that it has given you advantages over the other children, but do not think that you are better than they. If you do not reform, no one will love you, and then you will be the unhappiest of children for all your erudition!”

Sometimes he made up his mind to reform; but, unfortunately, the conceit in him was so strong that it drowned the voice of conscience, and each day he grew worse, and each day his classmates liked him less.

What is more, Alyosha became terribly naughty. Having no need to learn the lessons he was set, he got up to all sorts of pranks when the other children were doing their homework, and this idleness spoilt his character even more.

Eventually everyone grew so tired of his bad behaviour, that the schoolmaster seriously began to consider ways of reforming the naughty boy and to this end set him lessons two or three times longer than the others; but this was not the slightest help. Alyosha did not study at all, but nevertheless knew the lesson from beginning to end perfectly.

One day, not knowing what to do with him, the schoolmaster told him to learn about twenty pages by heart for the next morning, hoping that this would keep him quiet.

Not a bit of it! Our Alyosha did not give a thought to the lesson. That day he was intentionally more naughty than usual, and the schoolmaster threatened him in vain with punishment if he did not know the lesson next morning. Alyosha smiled to himself at these threats, sure that the hemp seed would help him.

The next day, at the appointed time, the schoolmaster picked up the book from which Alyosha had to learn the lesson, called him out and told him to recite it. The children watched Alyosha expectantly and the schoolmaster himself did not know what to think when Alyosha, in spite of the fact that he had not learnt the lesson the day before, rose boldly from his seat and went up to him. Alyosha did not doubt in the slightest that this time too he would be able to show his unusual ability; he opened his mouth... and could not say a word!

“Why are you silent?” the schoolmaster said to him. “Recite the lesson!”

Alyosha blushed, then turned pale, then blushed again. He began to wring his hands and tears of fear welled up in his eyes... all in vain! He could not utter a single word, because he had relied on the hemp seed and not even glanced at the book.

“What does this mean, Alyosha?” the schoolmaster shouted. “Why won’t you speak?”

Alyosha himself did not know the reason for this strange event. He put his hand into his pocket to feel the seed... But imagine his despair when he did not find it! The tears streamed from his eyes... he wept bitterly, but still could not say a word.

Meanwhile the schoolmaster had lost his patience. Accustomed to the fact that Alyosha always replied correctly without hesitation, he thought it impossible that the boy did not know at least the beginning of the lesson, and therefore put his silence down to obstinacy.

“Go to the dormitory,” he said, “and stay there until you know the lesson perfectly.”

Alyosha was taken to the lower storey, given the book and locked in.

As soon as he was left alone, he started to search for the hemp seed. He rummaged about for a long time in his pockets, crawled round the floor, looked under the bed, shook the blanket, pillows and sheet — all in vain! There was no trace of the precious seed anywhere! He tried to remember where he might have lost it, and eventually decided that he had dropped it the evening before when he was playing in the yard.

But how was he to find it? He was locked in the room, and even if they did let him into the yard, that would probably not help, for he knew that hens are fond of hemp seeds and one of them had probably managed to peck it up! Despairing of finding it, he thought of calling Blackie to his aid.

“Dear Blackie!” he said. “Dear Minister! Please come to me and give me another seed! I really will be more careful in future!”

But no one answered his request, and eventually he sat down on a chair and began to cry bitterly.

Meanwhile it was time for lunch; the door opened, and the schoolmaster entered.

“Do you know the lesson now?” he asked Alyosha.

Sobbing loudly, Alyosha was compelled to say that he did not know it.

“Then stay here until you do!” said the schoolmaster. He ordered the boy to be given a glass of water and a piece of rye bread and left him on his own.

Alyosha began to learn the lesson, but nothing would stay in his head. He had long since grown unaccustomed to studying, and in any case it was twenty printed pages! No matter how he tried, no matter how he strained his memory, when evening came he did not know more than two or three pages, and that badly.

When it was time for the other children to go to bed, his schoolmates rushed into the room at once, and with them came the schoolmaster again.

“Alyosha! Do you know the lesson?” he asked.

And poor Alyosha replied tearfully:

“Only two pages.”

“I see. Then tomorrow you will have to stay here with bread and water again,” said the schoolmaster. Bidding the other children good-night, he went out.

Alyosha was left with his schoolmates. When he had been good and modest, everyone had liked him, and if he were punished, they were sorry for him, and this comforted him. But now no one paid any attention to him: everyone looked at him scornfully and did not say a word to him.

He decided to strike up a conversation with a boy with whom he had once been very friendly, but the boy turned his back on him without replying. Alyosha addressed another boy, who did not want to talk to him either and even pushed him away, when he said something else to him. Then the wretched Alyosha realised that he deserved to be treated like this by his schoolmates. Bursting into tears, he went to bed, but could not get to sleep. He lay like this for along time, sadly recalling happy days in the past. All the children were sleeping sweetly, only he could not get to sleep. “Blackie has deserted me too,” thought Alyosha, and the tears welled up again in his eyes.

Suddenly... the sheet on the next bed stirred, as it had on that first day, when the black hen appeared to him.

His heart began to beat faster... he wanted Blackie to come out from under the bed, but dared not hope that his wish would come true.

“Blackie! Blackie!” he whispered finally.

The sheet lifted slightly, and the black hen flew up onto his bed.

“Oh, Blackie!” said Alyosha, beside himself with joy. “I dared not hope that I would see you! Have you forgotten me?”

“No,” she replied, “I could not forget the service you did me, although the Alyosha who saved me from death was not at all like the one I see before me now. You were a good boy then, modest and courteous, and everyone loved you, but now... I cannot recognise you!”

Alyosha wept bitterly, but Blackie continued to give him advice. She spoke to him for a long time and begged him tearfully to reform. Finally, when day began to break, the hen said to him:

“Now I must leave you, Alyosha! Here is the hemp seed you dropped in the yard. You were wrong to think that it was lost forever. Our King is far too generous to take this gift away from you for your carelessness. But remember that you gave your word to keep secret everything that you know about us... Do not add to your present bad qualities the even worse one of ingratitude, Alyosha!”

Alyosha took his precious seed from the hen’s claws in delight and promised to do his best to reform.

“You’ll see, dear Blackie,” he said, “I shall be quite different even today.”

“Do not think that it is easy to throw off bad habits once they have got a hold on you. Bad habits usually come in through the door, and go out through a crack, so if you want to reform, you must be strict with yourself all the while. But farewell, it is time for us to part!”

Left alone, Alyosha began to examine his hemp seed and could not feast his eyes on it enough. Now he was perfectly confident about the lesson, and his grief of yesterday had left no mark on him. He imagined happily how surprised everyone would be when he recited the twenty pages without a mistake, and the thought that he would again gain the upper hand over his schoolmates, who refused to talk to him, flattered his pride. He did not exactly forget about reforming, but thought it could not be as hard as Blackie said. “As if it did not depend on me to reform!” he thought. “I only need to want it, and everyone will like me again.” Alas, poor Alyosha did not know that to reform you must begin by getting rid of conceit and excessive self-reliance.

When the children assembled in the classrooms next morning, Alyosha was summoned upstairs. He entered with a gay and triumphant air.

“Do you know your lesson?” asked the schoolmaster, looking at him sternly.

“Yes, I do,” Alyosha replied boldly.

He recited the whole twenty pages without the slightest mistake or hesitation. The schoolmaster was beside himself with amazement, and Alyosha stared boldly at his schoolmates.

Alyosha’s proud air did not escape the schoolmaster’s eye.

“You know your lesson,” he said to him, “that is true, but why did you not want to say it yesterday?”

“I did not know it yesterday,” Alyosha replied.

“Impossible!” the schoolmaster interrupted him. “Yesterday evening you told me you knew only two pages, and that badly, but now you have recited all twenty without a mistake! When did you learn it?”

Alyosha kept silent. Finally he said in a trembling voice:

“I learnt it this morning!”

But then the children, stung by his arrogance, cried out in unison:

“He’s not telling the truth. He did not look at the book this morning.”

Alyosha shuddered, cast his eyes to the ground and said nothing.

“Answer me!” the schoolmaster continued. “When did you learn the lesson?”

But Alyosha remained silent: he was so taken aback by the unexpected question and the ill-will that his schoolmates had shown him, that he could not collect his thoughts.

Meanwhile, assuming that he had refused to recite the lesson the day before out of obstinacy, the schoolmaster deemed it necessary to punish him severely.

“The more abilities and talents you have from nature,” he said to Alyosha, “the more discreet and obedient you should be. You have not been given a mind to abuse it. You deserve to be punished for your obstinacy yesterday, yet today you have increased your guilt by lying. Gentlemen!” the schoolmaster continued, turning to the schoolboys. “I forbid you to speak to Alyosha until he has completely reformed. And since that is probably a minor punishment for him, get them to bring the birch.”

They brought the birch... Alyosha was in despair! This was the first time since the school was founded that someone had been punished with the birch, and who — Alyosha, who had such a high opinion of himself, who thought himself better and cleverer than anyone else! How humiliating!

He rushed up to the schoolmaster, sobbing, and promised to reform completely.

“You should have thought of that before,” was the reply.

Alyosha’s tears and repentance moved his schoolmates, and they began to intercede for him. But Alyosha, feeling that he did not deserve their compassion, cried even more bitterly.

“Very well!” said the schoolmaster, finally. “I forgive you at the request of your schoolmates, but on condition that you acknowledge your guilt before everyone and explain when you learnt the lesson.”

Alyosha lost his head completely... he forgot his promise to the underground king and his minister, and began to tell them about the black hen, the knights, the little people...

The schoolmaster did not let him finish.

“What!” he cried, angrily. “Instead of being sorry for your bad behaviour, you try to make me look a fool by telling a story about a black hen? That is too much. No, children, you see for yourselves that he must be punished!”

So poor Alyosha was birched.

Head hanging, Alyosha went downstairs to the dormitories. He was stupefied. Shame and repentance filled his heart. When a few hours later he quietened down somewhat and put his hand in his pocket... the hemp seed was not there. Alyosha burst into tears, sensing that he had lost it forever.

That evening, when the other children came to bed, he too went to bed, but could not get to sleep. How he repented of his bad behaviour! He resolved firmly to reform, although he realised it was impossible to get the hemp seed back.

Around midnight the sheet on the next bed stirred again... Alyosha, who had been overjoyed at this the night before, now closed his eyes: he was afraid of seeing Blackie! His conscience tormented him. Only yesterday he had told Blackie so confidently that he would reform, and instead of that... What was he to tell her now?

For a while he lay with his eyes closed. He heard the rustle of the lifting sheet... Someone came up to the bed, and a voice, a familiar voice, called his name:

“Alyosha! Alyosha!”

But he was ashamed to open his eyes, and meanwhile the tears were falling from them and trickling down his cheeks.

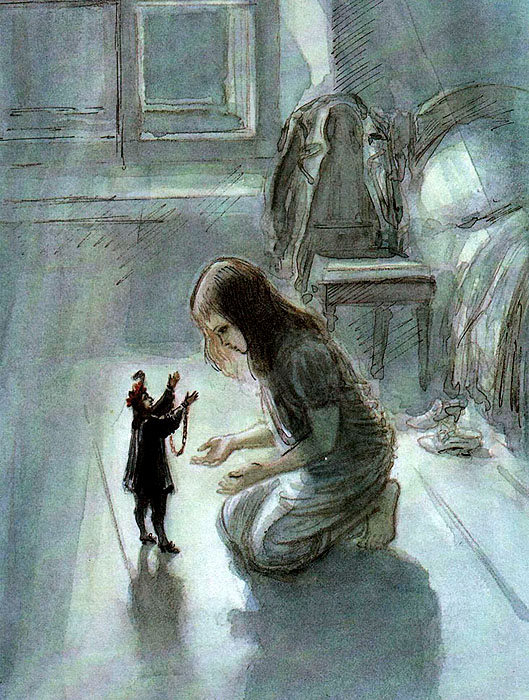

Suddenly someone tugged at the blanket. Alyosha looked up with a start: in front of him stood Blackie, not in the form of a hen, but in the black robe, with the crimson cap and the white starched neck-tie, just as he had seen her in the underground hall.

“Alyosha!” said the Minister, “I can see that you are not asleep. Goodbye! I have come to bid you farewell. We shall never meet again!”

Alyosha sobbed loudly.

“Goodbye!” he exclaimed. “Goodbye! And forgive me, if you can. I know I have done you wrong.” 63 “Alyosha!” said the Minister tearfully. “I forgive you; I cannot forget that you saved my life, and I still love you, although you have made me unhappy, perhaps forever! Goodbye! I have been allowed to see you for a short time only. This very night the King and his people are to move far away from here! Everyone is in despair, they are all weeping. We lived here for centuries so happily, so peacefully!”

Alyosha kissed the Minister’s small hands. As he caught hold of one hand, he saw something shining on it and heard a strange sound.

“What is that?” he asked in surprise.

The Minister raised both hands, and Alyosha saw that they were bound by a gold chain. He was horrified.

“Your indiscretion is the reason why I have been sentenced to wear these chains,” said the Minister with a deep sigh, “but do not cry, Alyosha! Your tears cannot help me. You alone can comfort me in my misfortune: try to reform and be the same nice boy you were before. Goodbye for the last time!”

The Minister pressed Alyosha’s hand and disappeared under the next bed.

“Blackie! Blackie!” Alyosha cried after him, but Blackie did not reply.

He did not sleep a wink all night. An hour before sunrise he heard sounds under the floor. He got out of bed, put his ear to the floor and listened for a long time to the clatter of small wheels and the sound of lots of little people walking past down below. This sound was mingled with the weeping of women and children and the voice of Minister Blackie, which shouted to him:

“Farewell, Alyosha! Farewell forever!”

The next morning when they awoke the children saw Alyosha lying unconscious on the floor. They picked him up, put him to bed and called for the doctor, who announced that he had a high temperature.

Some six weeks later Alyosha recovered, and all that had happened to him before his illness seemed like a bad dream. Neither the schoolmaster nor his schoolmates said a word to him about the black hen or about the punishment that he had received. Alyosha himself was ashamed to speak of it and strove to be obedient, good, modest and diligent. Everyone began to like him and be nice to him again, and he became an example to his schoolmates, although he could no longer learn twenty printed pages by heart, which, incidentally, he was not asked to do either.

Recommend to read:

Please support us

PayPal: anfiskinamama@gmail.com

Contact us if you have any questions or see any mistakes

© 2019-2026 Freebooksforkids.net