|

Free Online Illustrated Books for Kids |

Popular Andersen Fairy Tales Animal Stories Poetry for Kids Short Stories Categories list

Russian fairy tale

Go I Know Not Where, Fetch I Know Not What

Translated by Bernard Isaacs

freebooksforkids.net

Illustrated by N.Kochergin

In a certain tsardom there was a Tsar. He was a single man, unmarried, and he had in his service an Archer named Andrei.

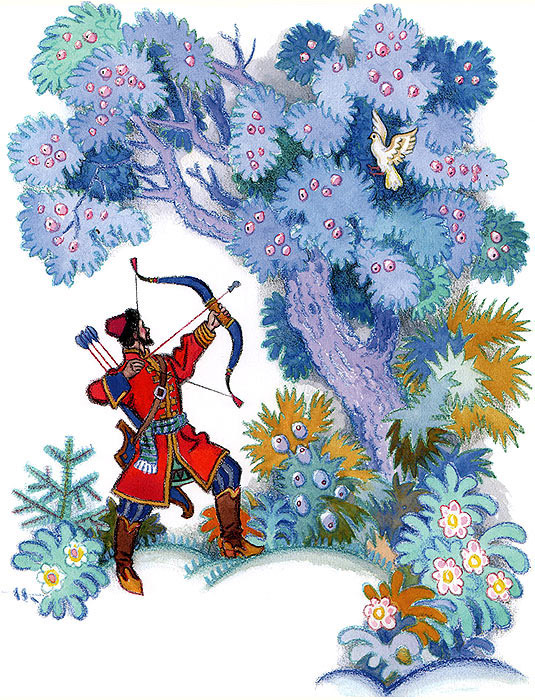

One day the Archer went out hunting. He tramped about the woods all day long, but no game came his way. It was getting late, so feeling weary and out of humour, he turned his way homewards. Suddenly he saw a turtle-dove sitting in a tree.

"I may as well have a shot at it," thought he.

So he shot and winged the dove, and it dropped from the tree on to the damp earth. Andrei picked it up and was about to wring its neck and put it in his pouch, when the bird spoke to him in a human voice and said:

"Do not kill me. Archer Andrei, do not wring my poor neck. Take me home alive and put me in the window. But mind, as soon as I begin to doze, slap me with your right hand, and great good fortune shall be yours."

Andrei the Archer could not believe his ears.

"What is this?" he thought. "The bird looks just like any other bird, yet it speaks in a human voice."

He took the dove home, put it in the window and waited.

By and by the dove tucked his head under its wing and dozed off, and Andrei, never forgetting what it had told him, slapped it with his right hand. The dove fell on the floor and turned into Tsarevna Maria, a maiden as fair as the sky at dawn, the fairest maiden that ever was born.

Said Tsarevna Maria to the Archer:

You have managed to catch me, now manage to keep me. Happy is the wooing that is not long a-doing. Marry me and I will make you a faithful and cheerful wife."

And so the matter was settled. Andrei the Archer married Tsarevna Maria, and he and his young wife were very happy together. But he did not neglect his duties. Every morning before daybreak he would go to the forest, shoot wild fowl and take them to the Tsar's kitchen. And thus it went on for a time, till one day Tsarevna Maria said:

"You and I are much too poor, Andrei."

"I'm afraid we are."

"If you borrow a hundred rubles and buy me silks with it, I shall see that our life is bettered."

Andrei did as she had told him. He went to his friends, borrowed a ruble here, two there, and bought silks with the money. He brought the silks to his wife, and she took them and said:

"Now go to bed; night is the mother of counsel."

Andrei went to bed, and Tsarevna Maria sat down to weave. All night long she wove, and she made a rug the like of which the world had never seen. On it was pictured the whole tsardom, with all its towns and villages, its woods and fields, the birds in the sky, the beasts in the woods, the fish in the seas, and the moon and sun shining down upon it all.

In the morning Tsarevna Maria gave her husband the rug and said:

"Take it to Merchants' Row and sell it, but mind do not name your own price. Take whatever they give you."

Andrei took the rug, hung it over his arm and went to Merchants' Row.

Presently a merchant ran up to him and said:

"How much do you want for the rug, my good man?"

"You are a merchant, name your own price."

The merchant thought and thought, but he could not price the rug. Then another came up, and after him another and still another. Soon there was a whole crowd of them. They all looked at the rug and marvelled, but none could price it.

Just then the Tsar's Councillor came riding by, and he wondered what all the to-do was about. He got out of his carriage, elbowed his way through the crowd and said:

"Greetings, merchants, from far lands and near. What is going on here?"

"We cannot price this rug," they said.

The Tsar's Councillor looked at the rug and was struck with wonder.

"Now tell me the truth. Archer, where did you get this marvellous rug?" he asked.

"My wife made it," said the Archer.

"And how much do you want for it?"

"I do not know. My wife said I was to take whatever I was given."

"Then here's ten thousand rubles, Archer."

Andrei took the money, handed over the rug and went home. And the Tsar's Councillor rode to the palace and showed the rug to the Tsar.

The Tsar looked, and he marvelled, for there was his whole tsardom before his eyes. It fairly took his breath away!

"Say what you like, but I shall not give you back this rug," said he.

Het got out twenty thousand rubles and gave them to his Councillor, and the Councillor took the money and thought:

"It does not matter, I shall have another, still better, made for myself."

He got into his carriage again and rode to the outskirts of the town. He found the hut in which Andrei the Archer lived and knocked at the door. Tsarevna Maria opened it, and the Tsar's Councillor put one foot over the threshold, but his other remained rooted to the ground. He lost his tongue and forgot what he had come for. There before him stood a woman so beautiful that he could have feasted his eyes on her for ever.

Tsarevna Maria waited for him to speak, and when he did not, she pushed him out and shut the door on him. After a while he collected his wits and betook himself home. But from that day on he could neither eat nor drink for thinking of the Archer's wife.

The Tsar saw the man was not himself and asked him what was wrong. Said the Councillor:

"Ah, Your Majesty, I have seen the Archer's wife and I cannot get her out of my mind. She has bewitched me, really and truly, and I can do nothing to break the spell."

Now this made the Tsar eager to take a look at the Archer's wife. He put on common clothes, went to the outskirts of the town, found the hut in which Andrei the Archer lived and knocked at the door. Tsarevna Maria opened it, and the Tsar put one foot over the thresh¬ old, but his other foot remained rooted to the ground. There he stood, and he was dumb with wonder for never had he seen anyone so beautiful!

Tsarevna Maria waited for the Tsar to speak, and when he did not, she pushed him out and shut the door on him.

The Tsar was badly smitten.

"Why should I live alone?" thought he. "Here is a lovely bride for me. She was meant to be a Tsar's wife, not an Archer's."

The Tsar went back to his palace, and a wicked plan took shape in his head: to steal his wife from a living husband. He sent for his Councillor and said:

Think of a way to get rid of Andrei the Archer. I want to marry his wife. If you help me, I shall reward you with towns and villages and gold, but if you do not, I shall cut your head off."

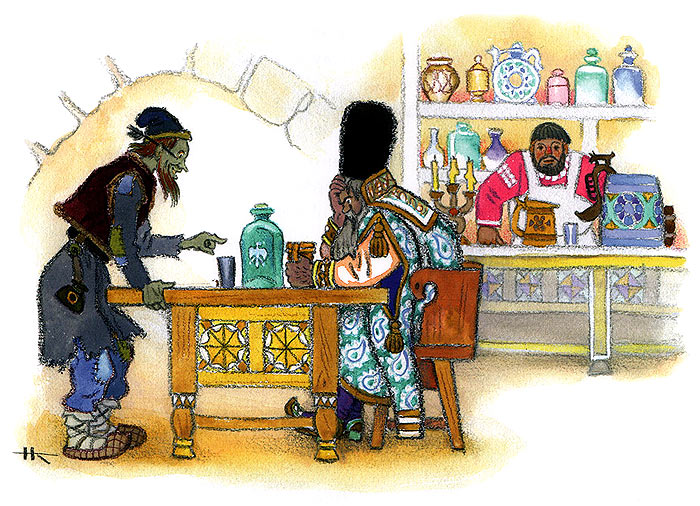

The Tsar's Councillor was sorely troubled. He could think of no way to get rid of the Archer, and so, looking sad and downcast, he went to a tavern to drown his sorrow in wine.

A tavern frequenter in a ragged caftan came up to him and said:

"Why do you look so sad. Tsar's Councillor? What is it that troubles you?"

"Be off with you, ragamuffin!"

"Better buy me a drink and I will give you some good advice."

The Tsar's Councillor gave him a glass of wine and told him his trouble.

"Andrei the Archer is a simple fellow," said the ragamuffin. "It would be easy to get rid of him if his wife were not so clever. We must think of something that will baffle even her. I believe I know what will. Go back and tell the Tsar to send Andrei the Archer to the Next World to find out how his dead father, the old Tsar, is doing. Andrei will go and never come back."

The Tsar's Councillor thanked the ragamuffin and ran back to the Tsar.

"I have thought of a way to get rid of the Archer," said he, and he told the Tsar what to do.

The Tsar was greatly pleased and sent at once for Andrei the Archer.

"Well, Andrei," he said, "you have served me faithfully, but there is one more service I must ask of you. Go to the Next World and find out how my father is doing. If you do not, I'll out with my sword and off with your head."

Andrei went home. He sat down on the bench and he hung his head.

"Why are you so sad, Andrei?" asked Tsarevna Maria.

Andrei told her what the Tsar wanted him to do.

"What a thing to worry about!" said Tsarevna Maria. "A trifling task; the real task is yet to come. Go to bed; night is the mother of counsel."

On the following morning, as soon as Andrei woke up, Tsarevna Maria gave him a bag of biscuits and a gold ring.

"Go to the Tsar and ask him to let you take the Councillor with you, so that he will know you have really been to the Next World. When you set forth with your way-companion, throw the ring in front of you and it will show you the way."

Andrei took the bag of biscuits and the ring, said good-bye to his wife and went to ask the Tsar to send his Councillor with him. The Tsar could not very well refuse, and he ordered the Councillor to go with Andrei. The two started out together, Andrei threw down the ring and off it rolled. He followed it through open fields and mossy marshes, across lakes and rivers, and behind him trudged the Tsar's Councillor. Whenever they grew tired of walking, they would eat some biscuits and then set off again.

Whether they walked for a long or a little time nobody knows, but by and by they came to a great, thick forest. They climbed down a deep ravine, and there the ring stopped.

Andrei and the Tsar's Councillor sat down to eat some biscuits. And who should they see but a doddering old Tsar pulling a cart of firewood, and a great big load it was, too, while two devils, one on his right, the other on his left, drove him on with cudgels.

"Look yonder,'' said Andrei. "Isn't that the Tsar's dead father?"

"It is indeed," said the Councillor.

"Hi, gentlemen!" shouted Andrei to the devils. "Let that old sinner go for a minute, I should like to have a word with him."

"Do you think we have time to stand about and wait?" replied the devils. "Or do you expect us to draw the wood ourselves?"

"I have a man here who can take his place," said Andrei.

So the devils unhitched the old Tsar and hitched the Councillor to the cart instead. They struck him with their cudgels, one on the left side, the other on the right, and the Councillor bent double but pulled as best he could.

Andrei asked the old Tsar how life was treating him.

"Ah, Archer Andrei," said the Tsar, "I am having a bad time of it in the Next World. Remember me to my son and tell him not to ill-treat people, or else he too will have a bad time of it when he gets here."

They had scarcely finished talking when the devils came back with the empty cart. Andrei took his leave of the old Tsar, the Councillor rejoined him, and they set out for home.

By and by they came to their own tsardom and went to the palace. The Tsar saw the Archer and he flew at him in a rage.

"How dare you come back!" he cried.

"I have seen your dead father in the Next World. He's having a bad time there," said the Archer. "He sends you his best wishes and says you are not to ill-treat people if you do not want to have as bad a time of it as he has."

"And how are you going to prove you have been to the Next World and seen my father?"

"I can prove it by the marks the devils' cudgels left on your Councillor's back."

That was proof enough, so the Tsar had to let Andrei go—what else could he do?

Said he to his Councillor:

"If you do not think of a way to get rid of the Archer, then I'll out with my sword and off with your head."

The Councillor was more troubled than ever. He went to the tavern, sat down at a table and called for wine. Just then the selfsame ragamuffin came up to him and said:

"What makes you so sad. Tsar's Councillor? What is it that troubles you? Buy me a drink and I will give you some good advice."

The Councillor gave him a glass of wine and told him his trouble.

"Do not worry," said the ragamuffin. "Go back and tell the Tsar to have the Archer do him this service—a thing hard to think of, let alone to do: he is to go beyond the Thrice-Nine Lands to the Thrice-Ten Tsardom and fetch Croon-Cat."

The Councillor ran off to the Tsar and told him how to get rid of the Archer. The Tsar sent for Andrei.

"Well, Andrei, you have done me one service, now do me another," said he. "Go beyond the Thrice-Nine Lands to the Thrice-Ten Tsardom and bring me Croon-Cat. If you do not. I'll out with my sword and off with your head."

Andrei went home with drooping head and told his wife what task the Tsar had set him.

"What a thing to worry about!" said Tsarevna Maria. "A trifling task; the real task is yet to come. Go to bed; night is the mother of counsel."

Andrei went to bed, and Tsarevna Maria went to the smithy and told the blacksmiths to forge three iron caps, a pair of iron tongs and three rods—one of iron, another of copper, and the third of tin.

Early next morning Tsarevna Maria woke Andrei up.

"Here are three caps, a pair of tongs and three rods—go beyond the Thrice-Nine Lands to the Thrice-Ten Tsardom. Three versts short of it, you will feel very sleepy—that will be Croon-Cat casting her spell over you. But mind you don't fall asleep. Fold your hands, drag your feet, and if need be, roll along the ground. If you fall asleep, Croon-Cat will kill you."

And telling him just what to do and how to do it. Tsarevna Maria saw him off on his errand.

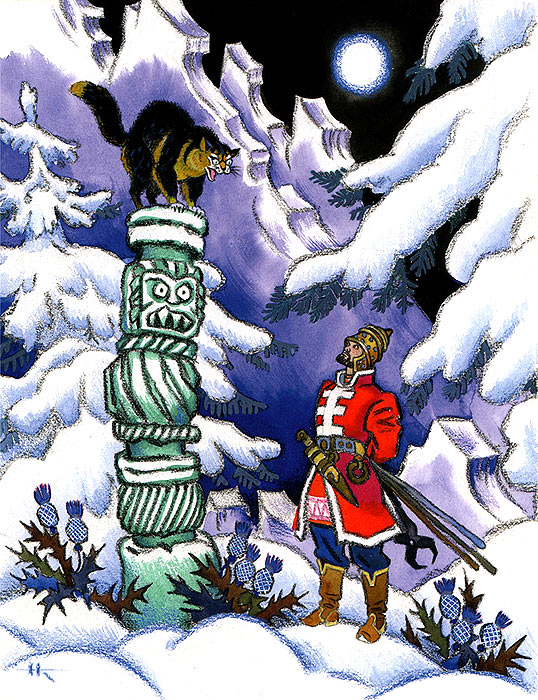

The tale is short in telling, but the deed is long in doing. Andrei the Archer came at last to the Thrice-Ten Tsardom, and three versts short of it he began to feel sleepy. He put the three iron caps on his head, folded his hands, dragged his feet, and when nothing else helped, rolled along the ground.

Somehow he managed to keep awake and found himself at a tall post.

When Croon-Cat saw Andrei she growled and snarled and jumped off the post straight on to his head. She broke the first cap, she broke the second, and was going for the third when Andrei caught her with the tongs, dragged her down to the ground and fell to trouncing her with the rods. First he whipped her with the iron rod; when the iron rod broke he flogged her with the copper rod; and when the copper rod broke he laid about him with the tin one.

The tin rod bent but did not break—it only curled round her body. As Andrei flogged her Croon-Cat told him fairy-tales about priests, about deacons, and about priests' daughters. But Andrei turned a deaf ear and flogged away with might and main.

That was more than Croon-Cat could stand, and, seeing that her evil spell did not work, she began to plead with him.

"Let me go, o good and kind man!" she said. "I will do anything you say."

"Will you go with me?"

"Anywhere you like."

Andrei turned homewards and took the Cat with him. When he came to his own tsardom he went to the palace with the Cat and said to the Tsar:

"I have done what you told me to do and brought Croon-Cat to you."

The Tsar could not believe his eyes.

"Come, Croon-Cat, show me fire and fury," he said.

At that the Cat began to sharpen her claws and glare at the Tsar, and made as if to rip open his breast and tear the living heart out of him. The Tsar was terrified.

"Do calm her, Andrei," he said.

Andrei quieted the Cat and locked her up in a cage, and then he went home to Tsarevna Maria. The two of them went on living happily together, but the Tsar grew more lovesick than ever. One day he sent for his Councillor again.

"You must think of some other way to get rid of Andrei the Archer. If you do not. I'll out with my sword and off with your head," said he.

The Councillor went straight to the tavern, sought out the ragamuffin, and asked him to help him out of his trouble. The ragamuffin tossed off his glass of wine, wiped his whiskers, and said:

"Go and tell the Tsar to make Andrei the Archer go I know not where and fetch I know not what. This task Andrei will never be able to fulfil, and so he will never come back."

The Councillor ran off to the Tsar and told him everything, word for word. The Tsar sent for Andrei.

"You have done me two services, now do me a third," he said. "Go I know not where and fetch I know not what. If you do this, I shall reward you handsomely, if you do not, I'll out with my sword and off with your head."

Andrei went home, sat down on the bench and wept.

"Why are you so sad, dear heart?" asked Tsarevna Maria. "Has anything happened to grieve you so again?"

"Ah," said he, "your fair face will be my ruin. The Tsar has commanded me to go I know not where and fetch I know not what. "

"Now that is a difficult task indeed. But never mind, go to bed; night is the mother of counsel."

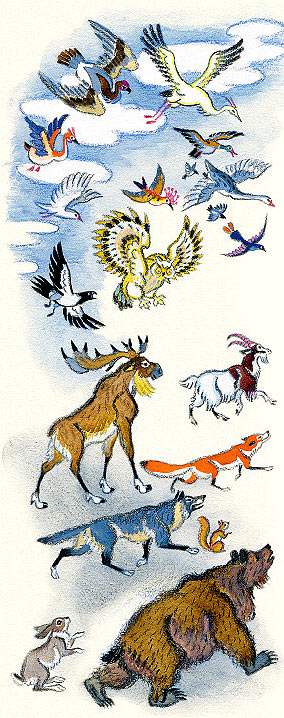

Tsarevna Maria waited for midnight, and then she opened her book of spells. She read it through, flung it aside and clutched her head: the book did not tell her how to fulfil the Tsar's task. She went out on to the porch, took out a kerchief and waved it, and lo! all kinds of birds came flocking and all kinds of beasts came running to her.

"Hail, Beasts of the Forest and Birds of the Skies!" said she. "You beasts prowl everywhere, you birds fly everywhere—perhaps you can tell me how to go I know not where and fetch I know not what?"

But the birds and beasts replied:

"No, Tsarevna Maria, we cannot tell you that."

Tsarevna Maria waved her kerchief again, and the birds and beasts vanished as if they had never been. She waved it a third time, and two Giants appeared before her.

"What is your wish? What is your will?"

"My faithful servants, carry me to the middle of the Ocean-Sea."

The Giants lifted Tsarevna Maria, carried her to the Ocean-Sea and stood in the middle of the deep waters. There they stood like two tall columns, holding her up in their arms. Tsarevna Maria waved her kerchief and all the fishes and crawling things of the sea came swimming towards her.

"Fishes and Crawling Things of the Sea, you swim everywhere and know all the islands—perhaps you can tell me how to go I know not where and fetch I know not what?"

"No, Tsarevna Maria, we have never heard of such a place."

Tsarevna Maria grew sad and woebegone and she told the Giants to take her home. And the Giants carried her to Andrei's house and set her down on the door-step.

On the following morning Tsarevna Maria was up betimes to see Andrei off on his journey, and she gave him a ball of yarn and an embroidered towel.

"Throw the ball of yarn in front of you and follow it wherever it rolls," she said. "And wherever you are, take care, after you wash, not to wipe yourself with any towel but the one I have given you."

Andrei said good-bye to Tsarevna Maria, bowed to all sides of him and went out through the town gates. He threw the ball of yarn in front of him, and went after it as it rolled on and on.

The tale is short in telling, but the deed is long in doing. Many a tsardom and strange land did Andrei pass. The ball rolled on and, as the yarn unwound, it became smaller and smaller. Soon it was no bigger than a hen's egg; and after a time it became so small that you could hardly see it in the roadway.

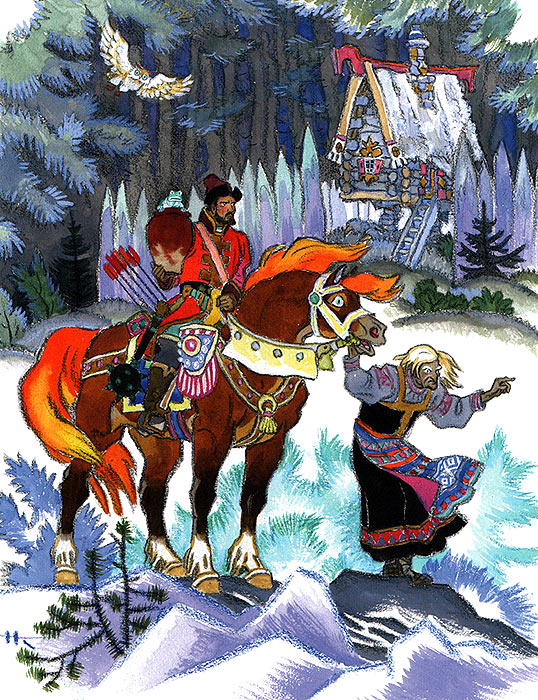

Andrei came to a forest, he looked, and there before him was a little hut on hen's feet.

"Little hut, little hut, turn your back to the trees and your face to me, please," said Andrei.

The hut turned round, Andrei went in and saw an old hag sitting on a bench spinning tow.

"Ugh, ugh, Russian blood, never met by me before, now I smell it at my door. Who comes here? Where from? Where to? I will roast you alive, eat you up and roll over your bones."

"Come, come, old Baba-Yaga, fancy eating a wayfarer!" said Andrei. "A wayfarer is lean and tough and grey with dust. Heat the bath first, wash me and steam me, and then eat me up."

So Baba-Yaga heated the bath-house. Andrei washed and steamed himself and got out his wife's towel to dry himself.

"How did you come by that towel?" asked Baba-Yaga. "My daughter embroidered it."

"Your daughter is my wife. It was she who gave me the towel."

"Ah, welcome, dear son-in-law, welcome, and let me treat you to the best my house can offer!"

Baba-Yaga bestirred herself and set all kinds of foods, wines and other good things upon the table. Andrei sat down without any fuss and fell to, and Baba-Yaga sat down beside him and asked him how he had come to marry Tsarevna Maria and whether they were happy together. And Andrei told her all about everything, and about how the Tsar had sent him he knew not where to fetch he knew not what.

"If only you would help me. Mother!" he said.

"Ah, my dear son-in-law, even I have not heard of so strange a place. The only one who knows of such things is an Old Frog, and she has been living in the marsh these three hundred years. But never mind, go to bed; night is the mother of counsel."

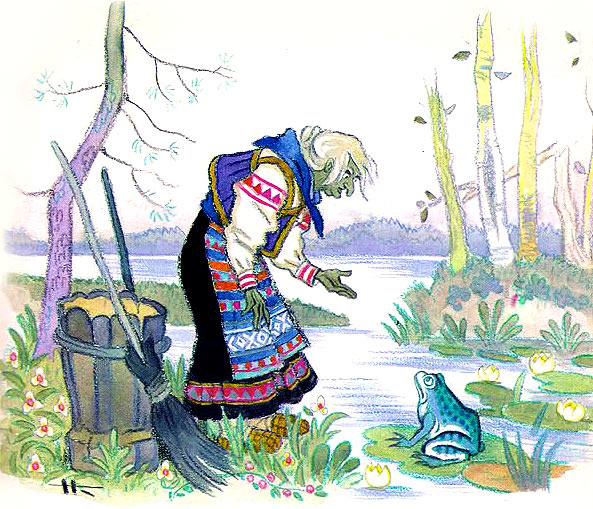

Andrei went to bed, and Baba-Yaga took two birch brooms, flew to the marsh and called:

"Old Mother-Hopper, are you still alive?"

"I am."

"Then hop out of the marsh."

The Old Frog hopped out of the marsh and Baba-Yaga said:

"Do you know where I know not what is?"

"I do."

"Then be so kind as to tell me where it is. My son-in-law has been sent I know not where to fetch I know not what."

"I would show him the way myself, but I am too old, it is a long hop," said the Frog. "Let your son-in-law put me into a jug of fresh milk and carry me to the Flaming River. There I shall tell him."

Baba-Yaga took Old Mother-Hopper, flew home, poured some fresh milk into a jug and put the Frog in it. Early next morning she woke Andrei up.

"Here is a jug with the Frog in it," she said. "Get dressed, mount my horse and go to the Flaming River. There you will leave the horse and take the Frog out of the jug. She will tell you where to go."

Andrei dressed, took the jug and got on Baba-Yaga's horse. Whether they rode for a long or a little time nobody knows, but at last they came to the Flaming River. Across that river no beast could jump, no bird could fly. Andrei got off the horse, and the Frog said:

"Take me out of the jug, my fine handsome lad. We must cross the river."

Andrei took the Frog out of the jug and set her on the ground.

"Now climb on my back."

"Oh, but you are so tiny, Mother-Hopper, I will squash you."

"Have no fear of that. Get on and hold fast."

Andrei sat down on Old Mother-Hopper, and she began to puff herself up. She swelled and she swelled until she was as big as a haycock.

"Are you holding fast?" she asked.

"That I am. Mother."

Old Mother-Hopper swelled and swelled again until she was as big as a haystack.

"Are you holding fast?"

"Yes, Mother."

Again she swelled and swelled until she was taller than the dark forest. Then in one hop she was across the Flaming River. She set Andrei down on the other side and became her own little self again.

"Follow that path, my fine handsome lad, and you will see a tower that is not quite a tower, nor quite a hut, nor quite a barn, but a little bit of each. Go inside and stand behind the stove. There you will find I know not what."

Andrei went down the path and saw an old hut that was not quite a hut. It had no windows or porch, but was enclosed by a paling. In he went and hid behind the stove.

By and by there was a din and clatter in the woods, and in came, very quick and nimble, a little bearded man the size of a thimble, and bawled out:

"Hi, Brother Naoom, I'm hungry!"

Scarcely were the words out of his mouth when lo and behold! a table appeared as if out of thin air, and on the table stood a barrel of beer, very light and clear, and a roasted ox with a knife stuck into it. Quick-and-Nimble-the-Size-of-a-Thimble sat down before the ox, pulled out the sharp knife and began to cut the meat, sprinkle it with garlic and polish it off with gusto, praising the food as he ate.

He ate up every bit of the ox and drank the whole barrel of beer.

"Hi, Brother Naoom, clear the table!"

And all at once the table vanished as if it had never been there, bones, barrel and all. Andrei waited until Quick-and-Nimble-the-Size-of-a-Thimble left, then he came out from behind the stove, plucked up courage and called:

"Brother Naoom, give me something to eat!"

Scarcely were the words out of his mouth when lo and behold! a table appeared as if out of thin air, and on it stood all kinds of foods and wines and other good things.

Andrei sat down at the table and said:

"Sit down. Brother Naoom, let us eat and drink together."

And an unseen voice answered:

"Thank you for your kindness, my friend. Many a year have I served here, yet never have I been given so much as a burnt crust, while you ask me to sit at your table."

Andrei watched and was stricken dumb with wonder. There was no one to be seen, yet the food vanished as if swept up with a broom; the wines and meads poured themselves into glasses and the glasses went clink-clank, hoppety-hop on the table.

"Brother Naoom, let me see you!" Andrei said.

"Nay. I am not to be seen. I am I know not what."

"Brother Naoom, would you like to serve me?"

"Indeed I would. You are a good and a kind man if ever there was one."

When they had finished eating, Andrei said:

"Clear the table and come with me."

He went out of the hut and looked round.

"Are you here. Brother Naoom?"

"Yes. Do not be afraid, I shall never leave you."

By and by Andrei came to the Flaming River, where the Frog was waiting for him.

"Well, my fine handsome lad," said the Frog, "did you find I know not what?"

"Yes, Mother-Hopper."

"Get on my back."

Andrei got on her back again and the Frog began to puff herself up, till she was very, very big, and then she gave a hop and carried him across the Flaming River.

Andrei thanked Mother-Hopper and set off homewards. He would go on a bit, then turn round and ask:

"Are you here, Brother Naoom?"

"Yes. Do not be afraid, I shall never leave you."

Andrei walked and walked, and at last he grew weary and footsore.

"Oh my," said he, "how tired I am!"

"Why did you not tell me before?" said Brother Naoom. "I could have got you home in no time."

And at once Andrei was caught up by a fierce gust of wind and whisked away over mountains and forests, over towns and villages. They flew over a deep sea, and Andrei was frightened.

"Brother Naoom, I should like to have a rest," said he.

The wind dropped at once and Andrei began to fall down into the sea. But where only blue waves had been splashing, he now saw an island, and on that island stood a palace with a golden roof and a beautiful garden all around it.

Said Brother Naoom to Andrei:

"Rest, eat, drink, and keep an eye on the sea. Three merchant ships will come sailing by. Hail them, invite the merchants to dinner and feast them royally—they have three marvels in their possession. Exchange me for those marvels—do not be afraid, I shall come back to you again."

Whether a long or a little time passed by nobody knows, but at last three ships came sailing from the West. The seafarers saw the island, and on it the palace with the golden roof and the beautiful garden all around it.

"What wonder is this?" said they. "Many a time have we sailed here, and never have we seen anything but the blue waves. Let us go ashore!"

The three ships cast anchor, and the three merchants got into a light boat and made for the island. And Andrei the Archer was on the shore, ready and waiting to greet them.

"Welcome, dear guests," said he.

The more the merchants saw, the greater was their wonder. The roof on the palace blazed like fire, birds sang in the trees and strange animals wandered about on the paths.

"Tell us, our good man, who built this wonder of wonders here?" the merchants asked.

"My servant, Brother Naoom, built it in a single night," Andrei replied.

He led the guests into the banquet hall, and said:

"Hi, Brother Naoom, give us something to eat and drink!"

All of a sudden—lo and behold!—a table appeared as if out of thin air, set with all the foods and wines the heart could desire. The merchants looked, and there was no end to their wonder and delight.

"Let us make an exchange, good man," said the merchants. "Give us your servant. Brother Naoom, and take any marvel you wish in return."

"Very well. What marvels can you offer?"

The first merchant took out a cudgel from under his coat. All one had to say was: "Now then, cudgel, give that man a trouncing!" and the cudgel would set to work and, no matter how strong he was, thrash the man to within an inch of his life.

The second merchant took out an axe from under his caftan and stood it on its handle, and the axe began to chop. Rap, tap—out came a ship; rap, tap—out came another, all complete with sails, and guns and sailors brave. The ships sailed, the guns fired and the brave sailors asked for orders.

He turned the axe upside down, and lo!—the ships vanished as if they had never been.

The third merchant took a reed pipe out of his pocket and blew upon it. And lo!—an army appeared, mounted and on foot, with rifles and cannon. The army marched, the bands played, the banners waved, and the horsemen galloped up and asked for orders.

Then the merchant blew into the other end of the pipe, and at once everything vanished.

"I like your marvels," said Andrei the Archer, "but mine is worth more. If you wish, I shall exchange Brother Naoom for all three of your marvels."

"Aren't you asking too much?"

"Please yourselves. It is that or nothing."

The merchants thought it over.

"What do we want with a cudgel, an axe and a pipe?" said they. "We had better exchange them for Brother Naoom; then we shall have all we want to eat and drink, night or day, without lifting a finger."

So the merchants gave Andrei the cudgel, the axe and the pipe, and shouted:

"Hi, Brother Naoom, you are coming with us! Will you serve us truly?"

"Why not?" came a voice. "It is all one to me whom I serve."

So the merchants went back to their ships and began to feast and make merry. They ate and drank, and they kept shouting:

"Step lively, Brother Naoom, bring us this, bring us that!"

They drank until they were dead drunk and dropped off to sleep where they sat.

And the Archer sat all by himself in the palace and felt very sad and miserable.

"Dear me," thought he, "I wonder where my faithful servant. Brother Naoom, is."

"Here I am. What do you wish?"

Andrei was overjoyed.

"Is it not time to go home, back to my young wife? Take me home. Brother Naoom."

And, as before, a blast of wind caught him up and carried him to his own land.

Now the merchants woke up, feeling sick and thirsty.

"Hi, Brother Naoom!" they shouted. "Give us something to eat and drink, and step lively!"

They called and shouted for a long time, but all in vain. They looked, and lo!—the island was gone. Only the blue waves splashed where it had stood.

Ther merchants were furious.

"What a bad man to have cheated us so!" they said.

But there was nothing they could do about it, so they weighed anchor and sailed off to wherever it was they were going.

Meanwhile Andrei the Archer flew home and alighted beside his hut. But where his hut had been there was now nothing but a charred chimney.

Andrei hung his head and went to a desolate spot by the blue sea. And there he was sitting and grieving when suddenly a blue-grey turtle-dove came flying up as if out of nowhere. It struck the ground and turned into his young wife, Tsarevna Maria.

They embraced and began asking each other questions and telling each other of all that had befallen them.

"Ever since you left home I have been flying about the woods and groves in the guise of a dove," said Tsarevna Maria. "Three times did the Tsar send for me, but they did not find me and so they burnt down our hut."

"Brother Naoom, can you raise a palace by the blue sea?" asked Andrei.

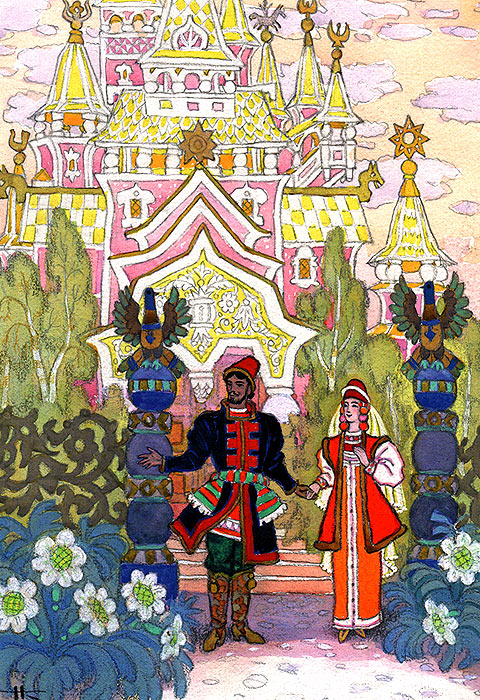

"Why not? It shall be done in the twinkling of an eye."

And true enough, before they could look round the palace was ready, and a grand palace it was, much better than the Tsar's. It stood in a great green garden and birds sang in the trees and all kinds of strange animals wandered about on the paths.

Andrei the Archer and Tsarevna Maria entered the palace, sat down by the window and began to talk, gazing at each other fondly the while. And so they lived without a care in the world for a day, and another, and a third.

Then the Tsar went out hunting and he saw a palace standing by the blue sea where nothing had stood before.

"What knave was built upon my land without my leave?" said he.

Off ran the Tsar's messengers, and when they came back they said that Andrei the Archer had built the palace and was living in it with his young wife. Tsarevna Maria.

The Tsar was angrier than ever, and he sent messengers to find out whether Andrei had been I know not where and fetched I know not what.

Off ran the messengers again, and when they came back they reported that Andrei the Archer had indeed been I know not where and fetched I know not what.

This sent the Tsar into a towering rage. He had his troops mustered and sent down to the sea, and commanded that the palace be razed to the ground and Andrei the Archer and Tsarevna Maria put to a cruel death.

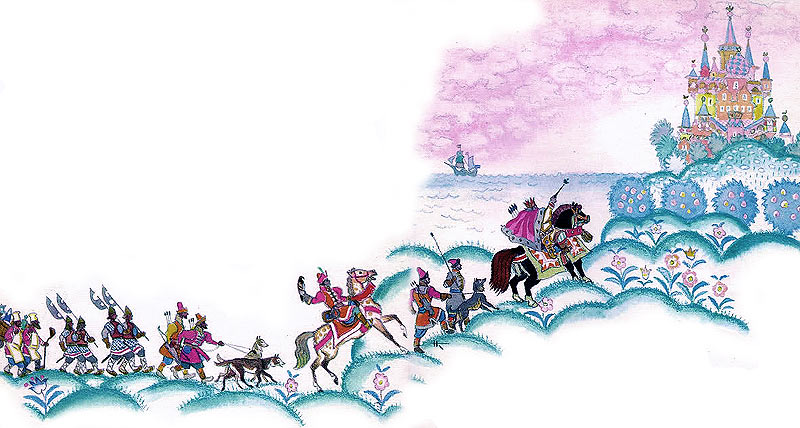

Andrei saw what a powerful army was coming against him, so he whisked out his axe and stood it on its handle. Rap, tap, went the axe, and a ship stood upon the sea; rap, tap, and there was another ship. The axe went rap-tap a hundred times till a hundred ships sailed upon the blue sea.

Andrei got out his pipe and blew on it—and an army appeared, mounted and on foot, with rifles, cannon and flying banners.

The captains galloped up and awaited orders, and Andrei ordered them to begin battle. The bands started playing, the drums rolled and the regiments moved into attack. The foot soldiers broke the ranks of the Tsar's army, and the horsemen galloped about taking prisoners. And the fleet of a hundred ships turned its cannon on the Tsar's town.

When the Tsar saw his troops fleeing, he rushed to stop them. At this Andrei got out his cudgel.

"Now then, cudgel, break the Tsar's bones for him!''

And off the cudgel went with a hop and a skip across the field. It caught up with the Tsar and struck him on the forehead and he fell down dead.

And that was the end of the battle. The people flocked out of the town and begged Andrei the Archer to take the rule of the realm in his hands.

To this Andrei agreed. He gave a grand feast, the like of which the world had never seen, and together with Tsarevna Maria he ruled the realm to the end of his days.

Author: Russian fairy tale; illustrated by Kochergin N.Recommend to read:

Please support us

PayPal: anfiskinamama@gmail.com

Contact us if you have any questions or see any mistakes

© 2019-2026 Freebooksforkids.net