|

Free Online Illustrated Books for Kids |

Popular Andersen Fairy Tales Animal Stories Poetry for Kids Short Stories Categories list

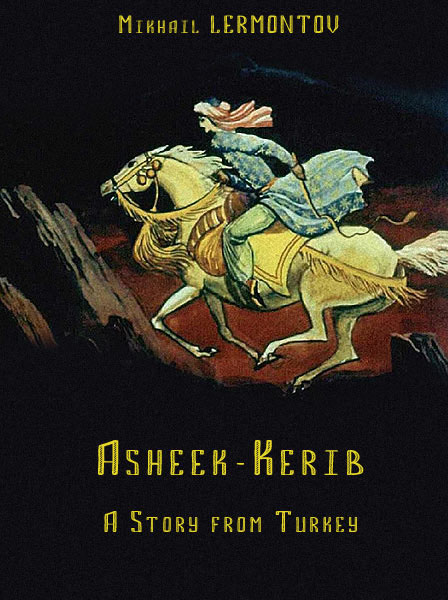

Mikhail Lermontov

Asheek-Kerib

A Story from Turkey

Translated by Avril Pyman

freebooksforkids.net

Illustrated by V.Psarryov

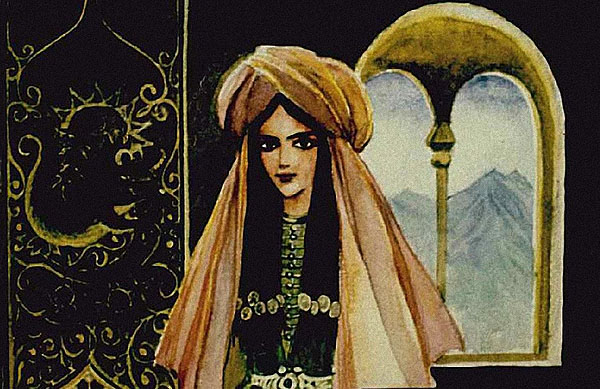

A long, long time ago, in the town of Tiflis, lived a very rich Turk.

Allah had given him much gold, but dearer than gold to him was his only daughter Magul-Megeri: the stars in the sky are beautiful but behind the stars live the angels, and they are still more beautiful. Even so was Magul-Megeri more beautiful than all the maidens of Tiflis.

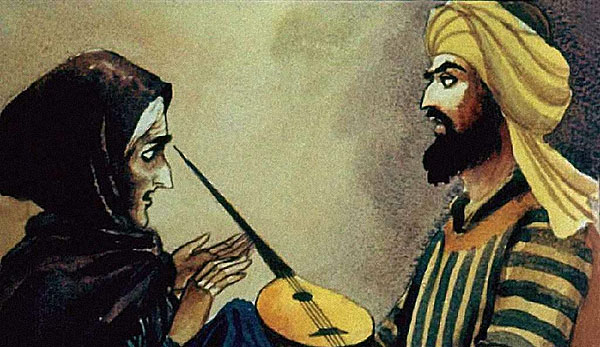

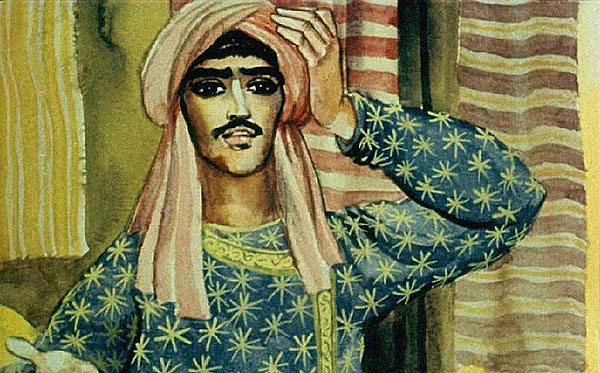

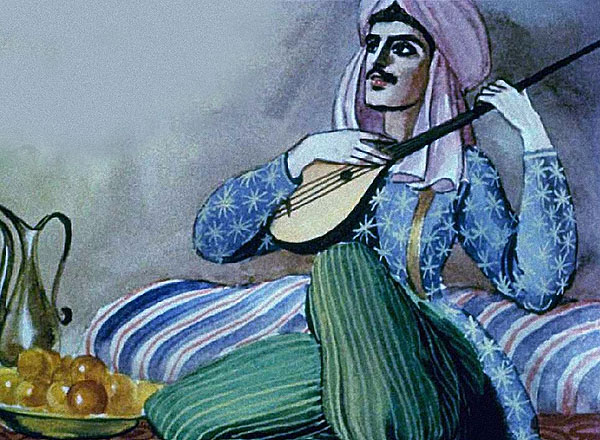

Also living in Tiflis was a certain poor man — Asheek-Kerib; the prophet had given him nothing but a noble heart — and the gift of song.

He would play on the saaz at the wedding-feasts of the rich and fortunate and sing the glories of the old heroes of Turkestan; at one such feast he set eyes on Magul-Megeri and they fell in love with one another. Little hope had poor Asheek-Kerib of ever winning her hand and he became as sorrowful as the sky in winter.

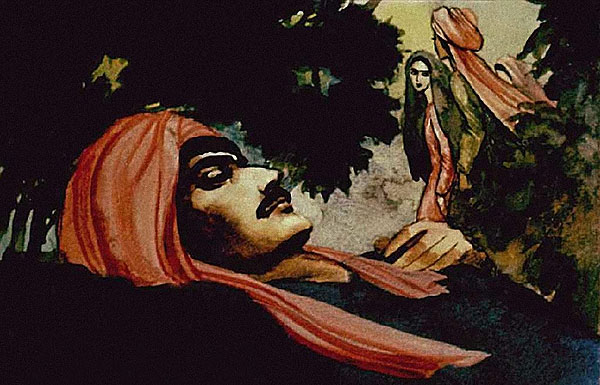

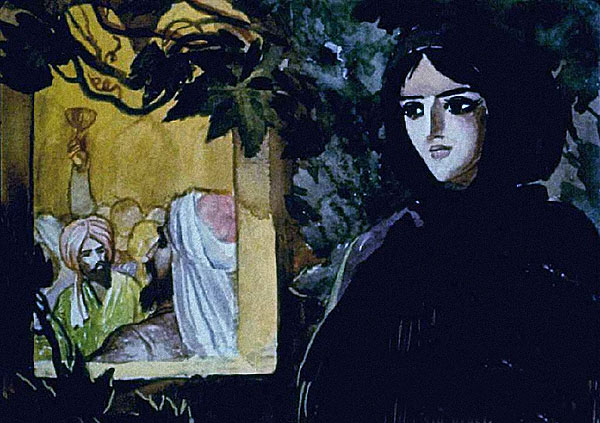

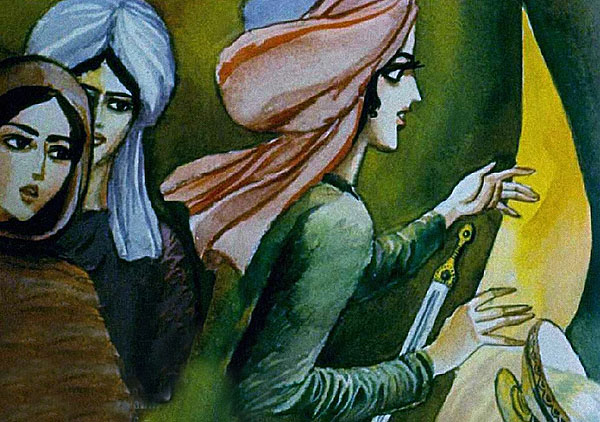

One day he was lying out in a garden under a grape vine and had at last managed to get off to sleep; just then Magul-Megeri happened to be passing with some of her friends.

Оne of them, seeing the sleeping Asheek (which means simply a minstrel, one who plays the saaz), dropped behind the others and went up to him:

“Why are you sleeping under that vine?” she sang. “Get up, you madman, your gazelle is passing!”

He woke up — the girl fluttered away, quick as a bird; Magul-Megeri heard her song and began to scold her.

“If only you knew,” her friend answered, “who it was that I was singing that song to, you would have said thank you: it was your Asheek- Kerib.”

“Take me to him,” said Magul-Megeri; and off they went.

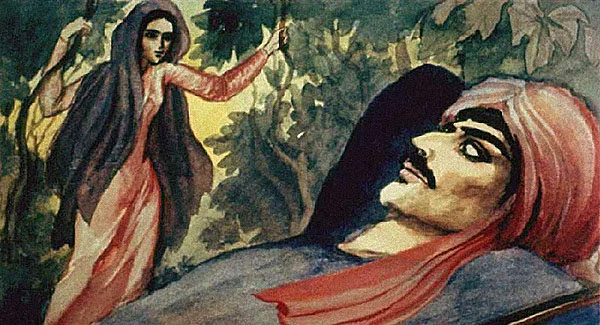

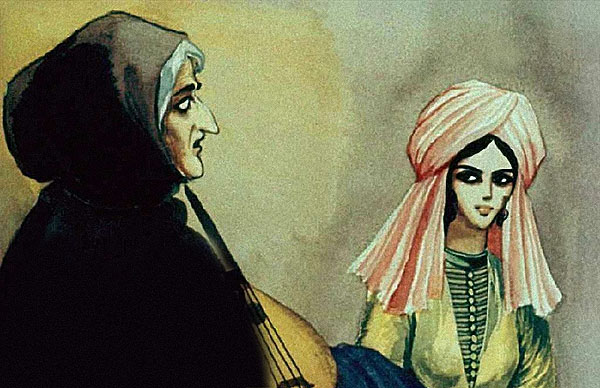

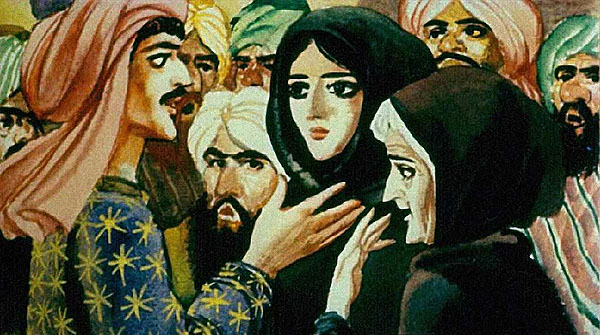

When she saw his sad face, Magul-Megeri began to put all kinds of questions to him and to comfort him.

“How can I help being sad,” replied Asheek-Kerib, “I love you and you will never be mine.”

“Ask my father for my hand,” she said, “and my father will pay for our wedding feast with his own money and will give me such a dowry as will suffice for us both.”

“All right,” he answered, “let us assume that Ayak-Aga will spare nothing for the happiness of his daughter; but who knows that afterwards you will not reproach me that I had nothing and owe everything to you; — no, dear Magul-Megeri; I have set myself a task; I promise to wander the earth for seven years and either to make my fortune or to perish in the deserts far away; if you agree to this then, when the time is fulfilled, you will be mine.”

She agreed, but added that if he did not return on the day agreed, she would wed Kurshud-Bek, who had long sought her hand.

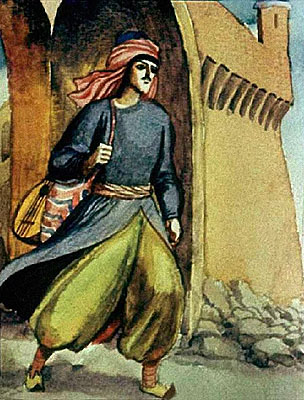

Asheek-Kerib went to his mother; he received her blessing on his journey, kissed his little sister, slung a pack over his shoulder, took a staff in his hand to lean on and left the town of Tiflis.

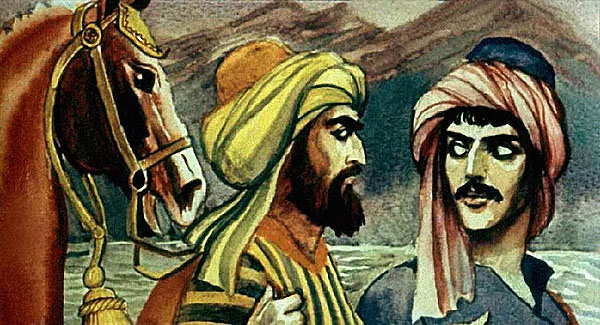

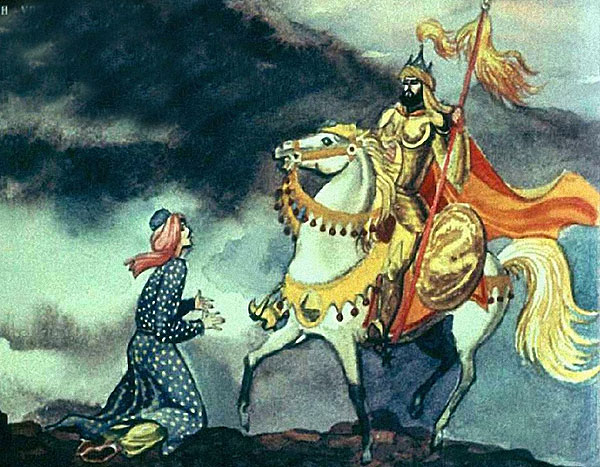

Then a horseman overtook him. He looked up — and it was Kurshud-Bek.

“A good journey to you,” called Kurshud-Bek, “wherever you go, wanderer, I will be your companion.”

Asheek was not best pleased with this companion but there was nothing he could do about it.

Аor a long time they continued on their way together, then they saw before them a river. There was neither bridge nor ford.

“Swim on,” said Kurshud-Bek, “I will come after you.”

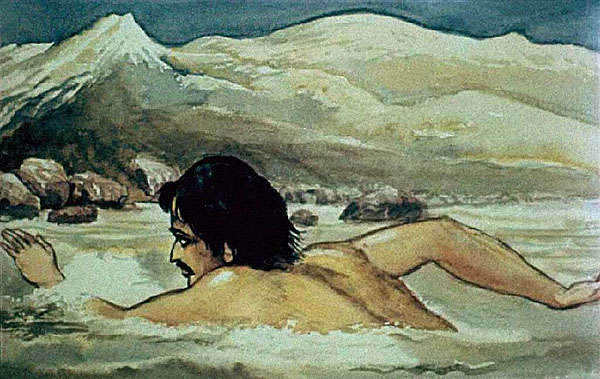

Asheek took off his upper garment and swam.

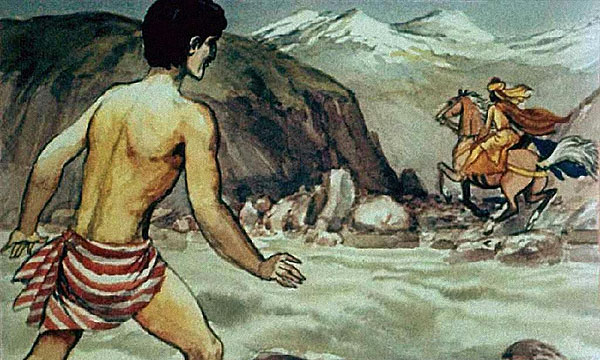

Having reached the other side he looked back and — oh sorrow! Oh Almighty Allah! Kurshud-Bek, having taken his robe, was galloping back in the direction of Tiflis, dust rising behind him in a long serpentine trail over the level plain.

When he reached Tiflis, Kurshud-Bek took Asheek-Kerib’s robe to his old mother.

“Your son has drowned in a deep river,” he said. “Here is his robe.”

In inexpressible distress, the mother fell on the clothing of her beloved son and began to shed bitter tears upon it.

Then she took the robe and carried it to her daughter-in-law elect, Magul-Megeri.

“My son has drowned,” she told her. “Kurshud-Bek has brought back his clothing; you are free.”

Magul-Megeri smiled and replied:

“Don’t you believe it, it’s all invented by that Kurshud-Bek: before seven years have passed no one shall be my husband.”

She took her saaz down from the wall and calmly began to sing poor Asheek-Kerib’s favourite song.

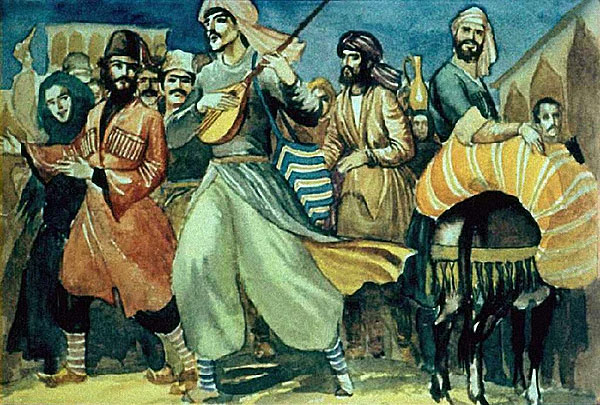

In the meantime the wanderer had arrived naked and barefoot at a certain village; kind people clothed and fed him; in return he sang them wonderful songs.

In this way he travelled on from village to village, from town to town, and his reputation grew and went on before him.

At length he arrived in Halaf; as was his custom he first visited the coffee-house, asked for a saaz and began to sing.

Now at this time there was a Pasha living in Halaf, a great amateur of minstrels.

Many were brought to him — but none pleased him; his chaushi (Junior rank in Turkish army) were quite exhausted with looking through the town; suddenly, as they were passing the coffee-house, they heard a remarkable voice; they rushed in —

“Come with us to the Great Pasha,” they shouted, “or we will have your head from your shoulders.”

“I am a free man, a wanderer from the city of Tiflis,” said Asheek-Kerib, “I go where I will and where I will not, there I do not go; I sing when the spirit moves me and your Pasha’s no master of mine.”

However, in spite of all this he was seized and borne off to the Pasha. “Sing,” said the Pasha, and he opened his mouth and sang.

And in this song he praised his beloved Magul-Megeri; and the song pleased the proud Pasha so much that he asked poor Asheek-Kerib to stay with him.

He showered him with silver and gold, his rich garments gleamed as he moved; merry and fortunate was the life of Asheek-Kerib and he became exceedingly rich.

Whether or not it was that he had forgotten all about his Magul-Megeri, the time he had set himself was running out and he was not even preparing to leave. The beautiful Magul-Megeri fell into despair; at this same time a certain merchant was about to set forth from Tiflis with forty camels and eighty slaves.

She called the merchant to her and presented him with a golden dish.

“Take this dish,” she said, “and display it in your stall in every town that you come to; then let it be proclaimed everywhere that whoever admits ownership of my dish and proves his claim may have it and its weight in gold into the bargain.”

The merchant set off on his travels and everywhere he went he did as Magul-Megeri had asked him, but none admitted ownership of the dish. He had sold almost all his goods when he arrived with the remainder in Halaf: here too he proclaimed what Magul-Megeri had bidden him throughout the town.

When Asheek-Kerib heard this he came quickly to the caravanserai: and there he saw the golden dish in the stall of the merchant from Tiflis.

“That is mine,” he said seizing it with one hand.

“It is yours indeed,” said the merchant. “I recognise you, Asheek-Kerib: get you to Tiflis as quick as you can: your Magul-Megeri told me to tell you that the time is running out and if you are not there on the day agreed she will marry another.”

In despair Asheek-Kerib took his head in his hands: only three days remained until the fateful hour.

Nevertheless he mounted his horse, took with him a considerable sum in gold coinage and galloped off not sparing his horse.

Finally the exhausted beast fell winded on the mount of Arzingan that is between Arzinyan and Arzerum. What was he to do: from Arzinyan to Tiflis was a two months’ journey and there were only two days left.

“Almighty Allah,” he cried, “if you do not help me now, then there is nothing left for me on this earth.”

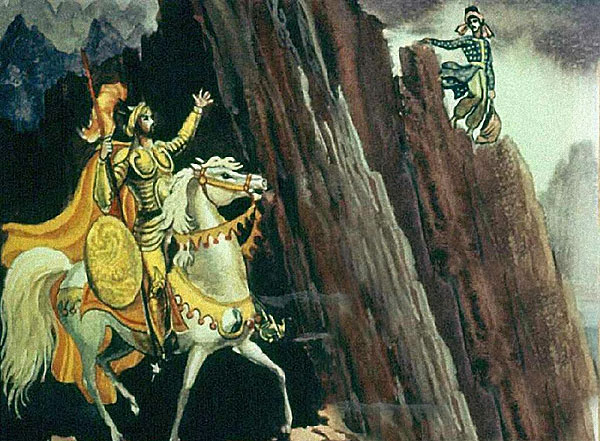

He wanted to throw himself from a high cliff; suddenly he saw at the bottom of the cliff a man on a white horse and heard a resonant shout:

“Hey there, what are you trying to do?”

“I’m trying to kill myself,” answered Asheek.

“Come down here, if that’s how things are, and I’ll kill you.”

Asheek climbed down.

“Come with me,” said the mounted man threateningly.

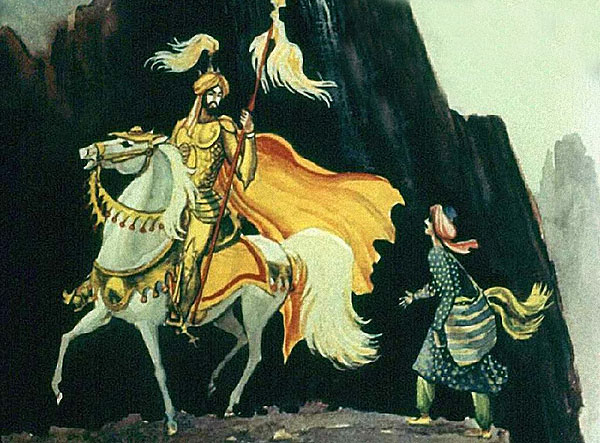

“How can I keep up with you?” asked Asheek. “Your horse flies like the wind and I am weighed down by my pack.”

“True; hang your bag on my saddle and follow me.”

Asheek-Kerib did his best to run but nevertheless began to lag behind.

“Why can’t you keep up?” asked the horseman.

“How can I keep up with you? Your horse runs swifter than thought and I am already exhausted.”

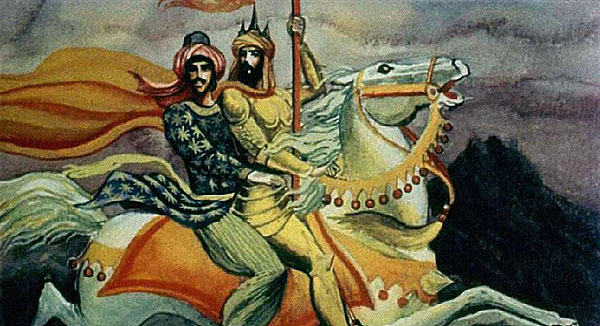

“True. Sit behind me on my horse and tell me the truth, where you wish to go.”

“If I could even get as far as Arzerum today,” answered Asheek.

“Shut your eyes, then.”

He shut them.

“Now open them.”

Asheek opened his eyes and looked. There before him shone the white walls and the minarets of Arzerum.

“I beg your pardon, Aga,” said Asheek. “I made a mistake. I meant to say that I should like to be in Kars.”

“There you are then,” the mounted man replied. “I warned you to tell me the real truth; shut your eyes again. Now open them.”

Asheek could not believe the evidence of his own senses: that it really was Kars. He fell on his knees and said:

“I have behaved very wrongly, Aga. Your servant Asheek is three times in the wrong: but you know yourself that if a man makes up his mind to tell lies in the morning he is obliged to go on lying till the end of the day: the place I really need to get to is Tiflis.”

“Well you are a man of little faith,” said the horseman angrily. “However, there’s nothing to be done about it: I forgive you: go on, shut your eyes. Now open them,” he added a moment later.

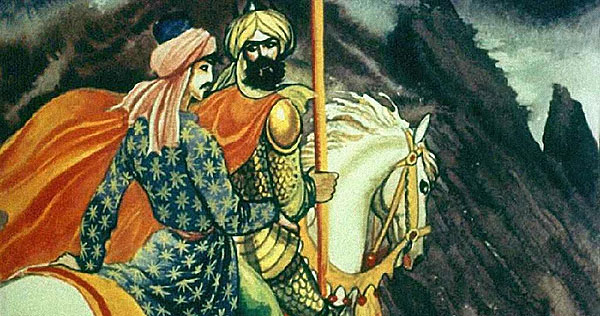

Asheek gave a cry of joy: they were at the gates of Tiflis. Thanking him sincerely and taking his bag from the saddle, Asheek-Kerib said to the horseman:

“Aga, of course, what you have done for me is very much; but do still more; if I tell people now how in one day I came from Arzinyan to Tiflis, no one will believe me; give me some proof.”

“Bend down,” said the man, smiling, “and take a handful of earth from under my horse’s shoe and hide it in your robe: then if people do not believe your words, order them to bring you a blind woman who has been in this state for seven years, rub the earth on her eyes and she will see.”

Asheek took the earth from under the horse’s foot but no sooner did he raise his head than horse and rider both disappeared; then it was that he believed in his heart that his patron had been none other than Haderiliaz (St. George).

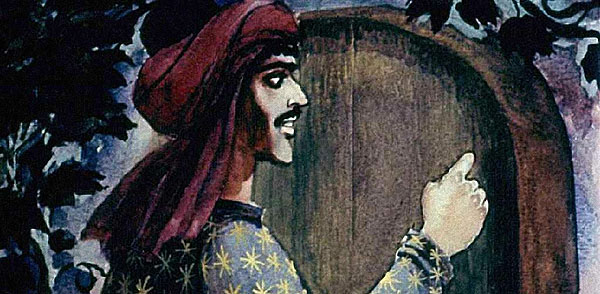

Only late in the evening did Asheek-Kerib reach his home: he knocked on the door with trembling hand and said:

“Ana, ana (mother), open the door: I am God’s guest; cold and hungry; let me in, please, for the sake of your wandering son.”

The old woman’s weak voice answered him:

“To shelter travellers there are the houses of the rich and the powerful: and there are weddings being celebrated in the town, too — you had better go there; you will have the chance to spend the whole night in pleasure.”

“Ana,” he replied, “I know no one here and so I beg you again: for the sake of your wandering son, let me in.”

Then his sister said to their mother:

“Mother, I will get up and open the door to him.”

“Worthless girl,” answered the old woman; “you are happy to take in young men and give them meat and drink because it is seven years now since I lost my sight from much weeping.”

Her daughter, however, taking no notice of her reproaches, opened the door and admitted Asheek-Kerib: having pronounced the customary greeting, he sat down and began to look around him with concealed anxiety: and on the wall he saw his sweet-voiced saaz hanging in a dusty cover. He asked his mother:

“What is that hanging on your wall there?”

—“You are curious, guest,” she replied. “Let it be enough for you that we give you a bite of bread and let you go on your way tomorrow with our blessings.”

“I have already told you,” he argued, “that you are my very own mother and this is my sister and for this good reason I beg of you to explain to me what it is you have hanging there on the wall.”

“It is a saaz, a saaz,” answered the old woman crossly, not believing a word he said.

“And what does ‘saaz’ mean?”

“Saaz means a thing to play on and sing songs to.”

Asheek-Kerib begged her to allow his sister to take the saaz down from the wall and to show it to him.

“No,” said the old woman. “That is the saaz of my unhappy son and it has been hanging on the wall for seven years now where no living hand has touched it.”

But his sister had already risen, taken the saaz down from the wall and given it to him: then he raised his eyes to heaven and prayed this prayer:

“O, Almighty Allah! if I am to achieve my end, then let my seven-stringed saaz be as perfectly tuned as on the day when I played upon it for the last time.”

And he struck the copper strings and the strings responded in perfect harmony: and he began to sing: “I am poor Kerib (a beggar), and poor are my words; but the great Haderiliaz helped me to descend from the high cliff, although I am poor and poor are my words. Recognise me, mother, know your wanderer.”

Upon which his mother burst into tears and asked:

“What is your name?”

“Rashid (the brave),” he replied.

“Once you have spoken, Rashid, and once you shall listen to me,” she said. “Your words have cut my heart to pieces. Tonight I saw in my sleep that the hair of my head had gone white, and it is seven years now since I lost my sight from much weeping; tell me, oh you who have his voice, when will my son come back to me?”

And twice she repeated her question with tears. In vain he told her that he was her son, she did not believe him and after a while he asked:

“Mother, permit me to take the saaz and to go. I have heard there is a wedding near here: my sister will show me the way; I shall play and sing, and everything I receive I shall bring back here and share with you.”

“No,” said the old woman, “since my son left, his saaz has not once been out of this house.”

But he began to promise that he would not harm so much as a single string.

“And if but one string breaks,” Asheek went on, “I shall give you all my property as a forfeit.”

The old woman felt his bags and realising that they were full of coins, she allowed him to go; having accompanied him to a rich house where a noisy wedding feast was in progress his sister waited in the doorway to see what would happen.

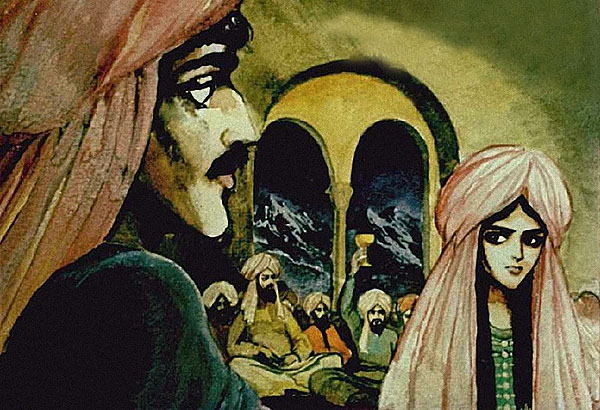

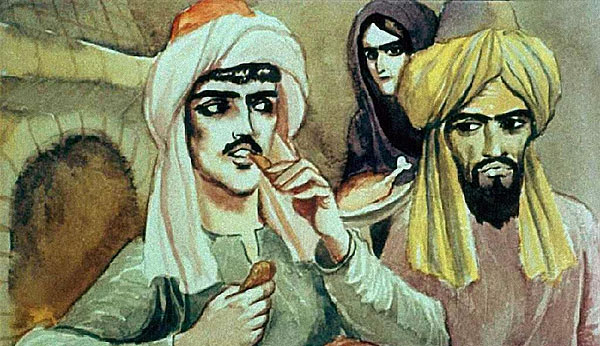

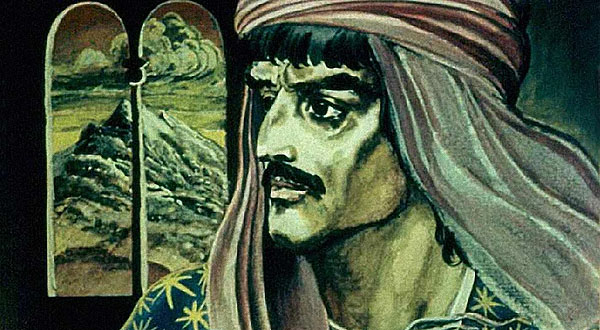

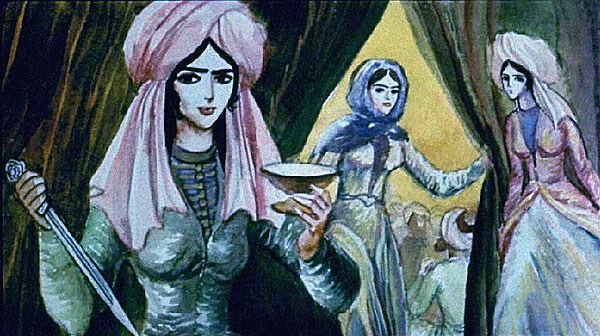

In this house lived Magul-Megeri, and that very night she was to become the wife of Kurshud-Bek. Kurshud-Bek was feasting with his friends and relatives, but Magul-Megeri, sitting behind a rich curtain with her friends, held in one hand a cup of poison and, in the other, a sharp dagger; she had sworn to die rather than let her head rest upon the pillow with Kurshud-Bek.

From behind the curtain she heard that a stranger had come, who said:

“Salaam aleikum: you are merry here and make feast, so permit me, a poor wanderer, to sit amongst you and for that I will sing you a song.”

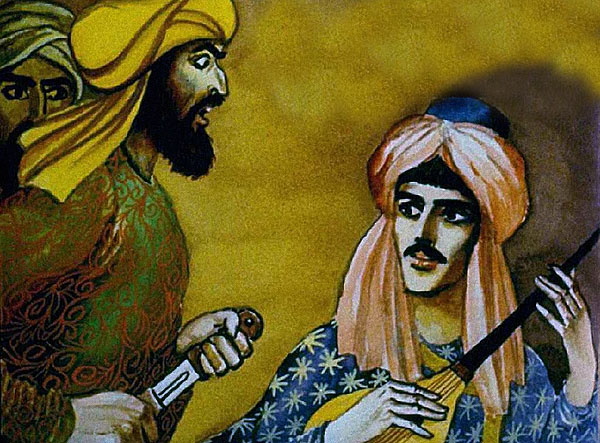

“Why not?” said Kurshud-Bek. “The doors are open to all singers and dancers, because we are celebrating a wedding. Sing us something, Asheek (minstrel) — and I will send you on your way with a whole fistful of gold.” Then Kurshud-Bek asked him: “And what is your name, traveller?”

“Shin di-Gyorursez (you will soon find out).”

“That is a strange name,” the other exclaimed, laughing. “It’s the first time I have heard it!”

“When my mother bore me and laboured in pain at my birth, then many neighbours came to the doors and asked whether it were a boy or a girl God had given her; they were answered: ‘Shindi-gyorursez (you will soon find out).’ And that is why — when I eventually was born — I was given that name.”

Thereupon he took his saaz and began to play:

“In the town of Halaf I drank wine of Misir, but God gave me wings and I flew hither in one day.”

Kurshud-Bek’s brother, a rather stupid man, drew his dagger and shouted:

“You are lying: how could you come here from Halaf in one day?”

“Why do you want to kill me?” asked Asheek. “It is usual for singers to assemble at one place from far and wide; and I take nothing from you, believe me or believe me not.”

“Let him go on,” said the bridegroom, and Asheek-Kerib took up his song again. “I made my morning prayer in the valley of Arzinyan, my noon-tide prayer in the town of Arzerum; before the setting of the sun I made my prayer before the town of Kars, and my evening prayer in Tiflis. Allah gave me wings, and I came flying hither; may God grant that I be as a sacrifice to the white stallion, for he galloped swiftly, surefooted as a tight-rope walker, from the mountain into the ravine and from the ravine into the mountain: Maulyam (the Creator) gave Asheek wings, and he has come to the wedding of Magul-Megeri.”

Then Magul-Megeri, recognising his voice, threw the dagger one way and the cup of poison the other.

“So that is how you keep your oath,” said her friends. “This way you will be the wife of Kurshud-Bek this very night.“

“You did not know him, but I know the voice of my beloved,” answered Magul-Megeri and, taking a pair of scissors, she cut through the curtain.

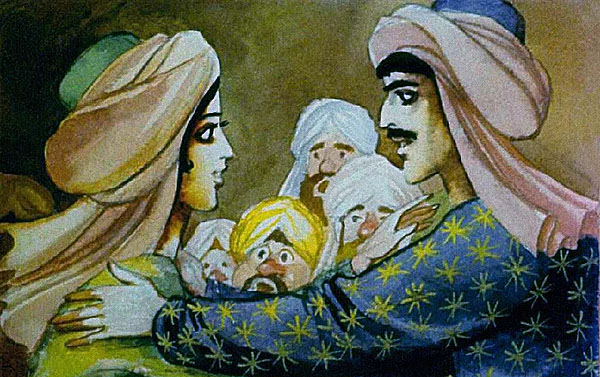

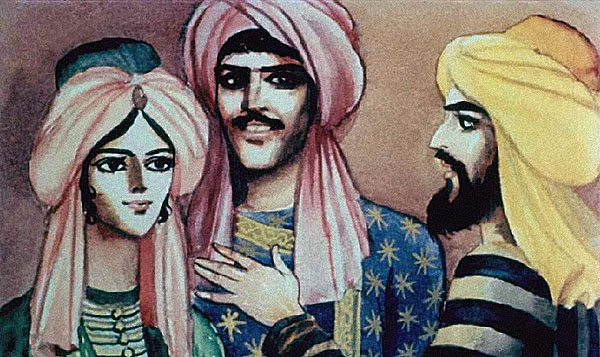

When she had peeped through and seen that it was indeed her Asheek- Kerib, she cried out, then she flung herself on his neck and both fell to the ground in a dead faint.

Kurshud-Bek’s brother rushed to them with his knife, intending to stab them both but Kurshud-Bek stopped him, saying:

“Calm yourself and know that what is written on a man’s brow at birth is not thereafter to be avoided.”

When she came to her senses, Magul-Megeri grew red with shame, covered her face with her hands and hid behind her curtain again.

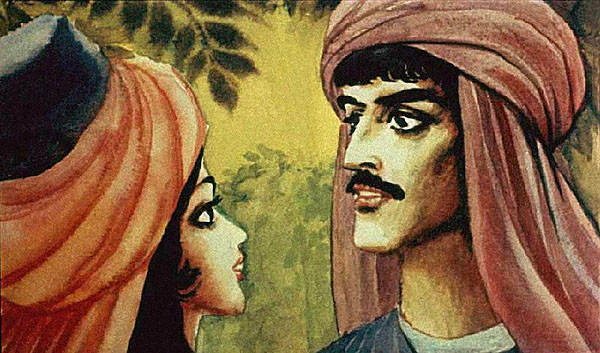

“Now I see very well that you are Asheek-Kerib,” said the bridegroom. “But tell us how you managed to travel so great a distance in so short a time.”

“To prove the truth of what I say,” replied Asheek, “my sabre will cut through stone and if I lie, may my neck be so thin that it will not hold up my head; but best of all bring me some blind woman who has not seen God’s world for seven years, and I will give her back her sight.”

Asheek-Kerib’s sister, who was still standing at the door, ran for her mother when she heard these words.

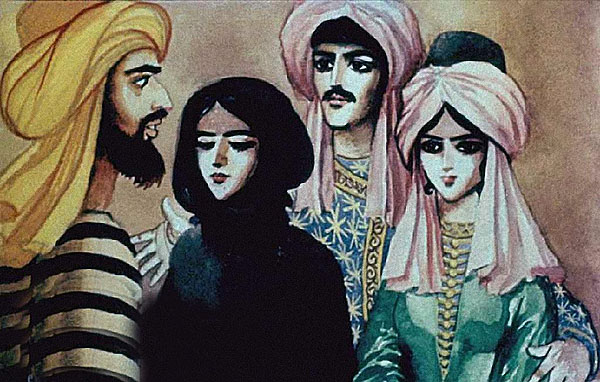

“Mother!” she cried, “it really is my brother and your son Asheek-Kerib,” and, taking her by the arm, she led the old woman back to the feast.

Then Asheek took the earth from his breast, mixed it with water and pasted it onto his mother’s eyes, saying:

“Know, all ye people, how great and powerful is Haderiliaz,” and his mother’s eyes were opened and she saw.

After this no one dared to doubt the truth of his words, and Kurshud-Bek surrendered the beautiful Magul-Megeri without a word.

Then in his gladness Asheek-Kerib said to him: “Listen, Kurshud-Bek, I shall comfort you. My sister is no less beautiful than your former bride and I am rich; she will have no less silver and gold; so take her for yourself, and be as happy as I shall be with my beloved Magul-Megeri.”

Recommend to read:

Please support us

PayPal: anfiskinamama@gmail.com

Contact us if you have any questions or see any mistakes

© 2019-2026 Freebooksforkids.net